5 The Frontier and the West

Theodore Gracyk

Authorship

Sections 5.1, 5.2, and 5.4 are edited, remixed, extensively rewritten and expanded by Theodore Gracyk, using material in Chapter 7 of American Encounters: art, history, and cultural identity, which is authored, remixed, and/or curated by Angela L Miller, Janet Catherine Berlo, Bryan J Wolf, and Jennifer L Roberts and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. All other material authored by Theodore Gracyk.

Chapter Goals

- Understand the myth of the vanishing race

- Explore examples of voice appropriation supporting the myth

- Understand racial stereotyping of Indigenous peoples

- Define Manifest Destiny

- Explore examples of appropriation supporting Manifest Destiny

- Understand images of tipis as a racial stereotype

5.1 Manifest Destiny

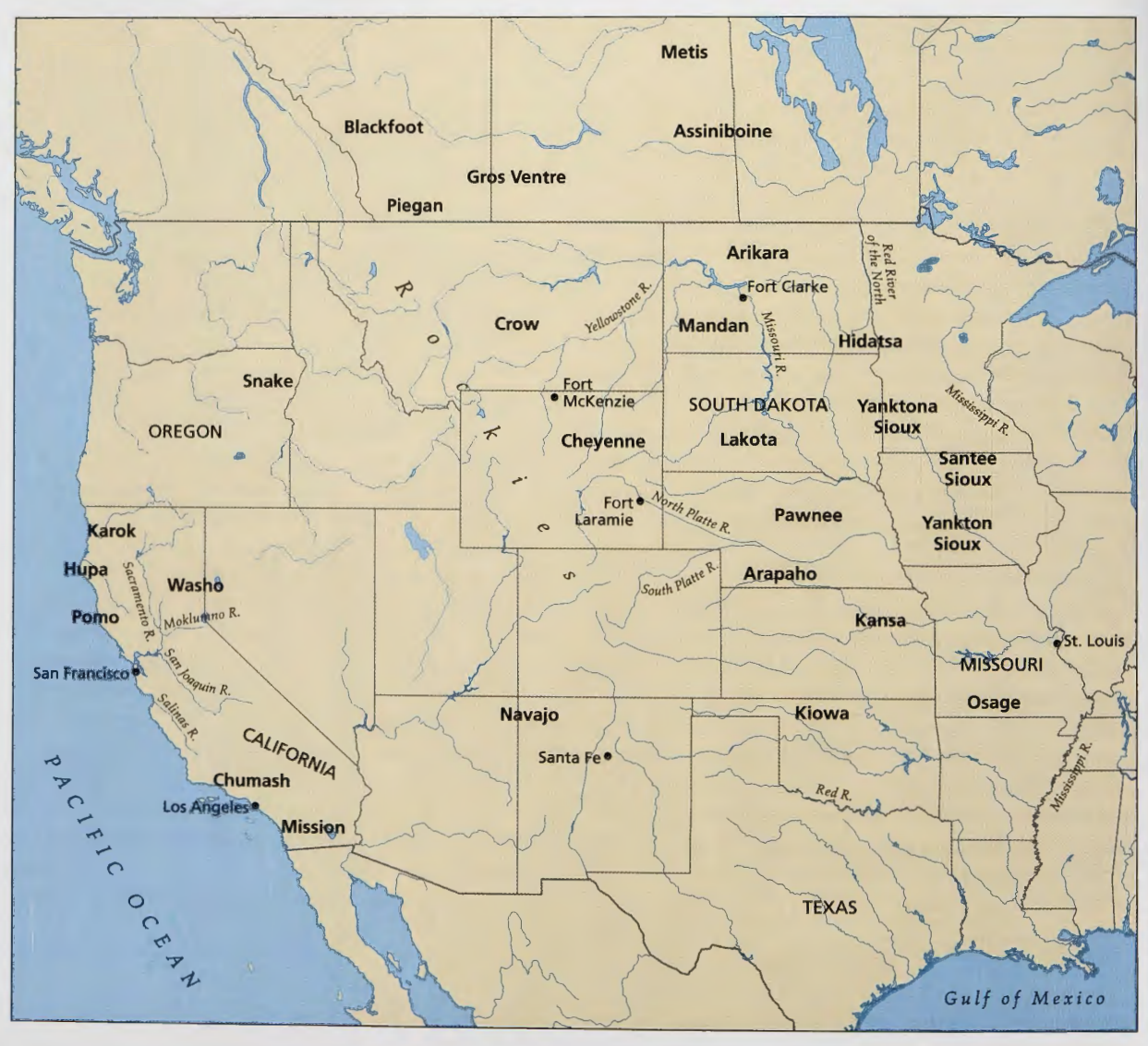

This chapter considers the second great era of encounter between Indigenous and settler cultures. This phase of encounter occurred primarily in the region known as the Great Plains, the vast plateau stretching from the Mississippi River west to the Rockies, and from Texas north into Canada. (See figure 5.1.) From the late 18th century on, contact with trappers, trading companies, and explorers vastly expanded Indigenous networks of exchange. At first, trappers and traders were searching for the beaver pelts that been the major trade good with Indigenous peoples in previous centuries, supplies of which had been exhausted in the East. Later, plentiful deer, antelope, and buffalo hides attracted more traders and trappers to the West. The explorers came in search of data about the landscape, especially geological features and natural resources that might support colonization. Then, beginning in the 1840s, settlers from the East spread westward in pursuit of the new lands of the frontier. Indigenous peoples controlled much of this region well into the 19th century, and historians of the American West generally agree that the United States did not gain full control of the Plains until about 1890.

What distinguished this second era of encounter was the emergence of the ideology of Manifest Destiny and an emerging expectation that the United States’s political and social future lay in the West. (See a discussion of the origins of the doctrine in Chapter 4, Section 4.4.) This widely shared view was driven by a sense of racial and national entitlement: the conviction that American democratic institutions — of northern European and Anglo-Saxon ancestry — were destined by providence to triumph over all other groups that claimed the land (Horsman 1981). Although the idea of Manifest Destiny arose in relation to other issues, it pitted the ambitions of the young nation against its territory’s Indigenous occupants. Basically, it proclaimed a Protestant Christian mission to redeem the wilderness from Indigenous peoples, Catholic Hispanics, and the mixed races of the Mexican frontier. In other words, it became official U.S. policy to replace the original and existing occupants with an overwhelming number of white Protestant settlers.

Three events in quick succession expanded the United States from coast to coast. First came the annexation of Texas in 1845, then of the Oregon Territory in 1846 following settlement of a boundary dispute with Great Britain, and then came the Mexican surrender of land that concluded the Mexican-American War (1846-8). As a result, the vast territories of California, the Southwest, and the Pacific Northwest joined the Union. Southern slaveholding interests drove expansion as well, bringing a tense political antagonism to the process of national growth that would become the major cause of the Civil War (1861-5).

The 19th century differed from the preceding three centuries of frontier encounters not only in the assumption of racial supremacy that energized it, but also (paradoxically) in the impulse to document those very cultures whose way of life was threatened by this supremacy. These visual documents — “witnesses to a vanishing America” — were motivated by a desire to create a record of cultures believed to be on the edge of extinction.

5.2. The Louisiana Purchase and the American Interior

In 1803, the United States bought out French claims to possess large areas of land to the west of the Mississippi river. Technically, the U.S. did not buy the land. The U.S. bought the right to acquire the land from the Indigenous peoples who possessed it. In practical terms, the “Louisiana Purchase” effectively doubled the size of the country. In 1804, President Thomas Jefferson sent men under the command of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to survey the area and to locate the best routes for travel across it to the Pacific Ocean. They were also directed to document and establish ties with the tribes they encountered. During their first winter of exploration, they built a fort in central North Dakota on the land of the Mandan tribe. In November, 1804, the fort was visited by a French fur trapper and his fifteen-year-old “wife,” Sakagawea. The trapper claimed that he had purchased her from members of the Hidatsa tribe. He said that members of that tribe had kidnapped her when she was twelve during a raid on her people, the Shoshoni, at a location near the present-day Idaho-Montana border. Therefore, she knew the language spoken in the area they would next explore. Lewis and Clark hired the trapper and Sakagawea as language interpreters for their travels west of the Mandan area. Because none of the Americans could could communicate with Sakagawea directly, they accepted what the trapper said about her. However, his story about her Shosoni heritage was probably a lie to get them to hire him, because when they encountered the Shosoni people, she could not communicate with them. The exploration party successfully reached the Pacific Ocean. The Lewis and Clark expedition returned to the United States in 1806.

In 1807, expedition member Patrick Gass published the first account of the trip as A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery. Advertised as a source of both “amusement and information,” the book’s success demonstrated public interest in (to quote Gass) “numerous, powerful and warlike nations of savages” in the American interior. Increased interaction with Plains tribes in the next several decades led many others to commercialize the public’s interest in the peoples of the Plains.

In 1824, Philadelphia artist George Catlin decided to pursue a career addressing this market, and in 1830 he took his first of five trips into the area that had been explored by Lewis and Clark. In 1837, he assembled his “museum,” which was a traveling exhibition with an entrance fee. The show held 422 oil paintings depicting Indigenous life on the plains. (See figure 5.2.) There were also landscapes of the Missouri and Mississippi valleys.

Catlin explicitly advertised his project, as did other similar galleries during these same decades, as a mission of cultural preservation. He wrote in Letters and Notes on Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians (1841) that he wished “to fly to their rescue, not of their lives or their race (for they are doomed and must perish) but … of their looks and modes.” The idea that the images were “witnesses to a vanishing America” was central to their marketing. In other words, the goal was content appropriation on a vast scale.

Like many 19th-century artists, Catlin sketched his subject and then, back home in his studio, recreated and finalized the image in the form of an oil painting. Catlin accurately recorded the clothing and body paint of the Indigenous peoples he visited. In the late 20th century, a number of the ancestors of the people he documented used his portraiture to reconstruct their own traditional ceremonial dress for pow-wows. Consistent with older traditions of portraiture, the majority of Catlin’s paintings are of important male figures, such as chiefs, warriors, and medicine men. He also painted a few women, scenes of sport competitions, methods of buffalo hunting, and sacred ceremonies. In 1844, number of these pictures were published as lithographic prints in his North American Indian Portfolio. Lithography was a new method of relatively cheap printing that allowed for highly detailed reproduction on a mass scale. Like the Currier and Ives lithographs discussed in Chapter 4 (see figures 4.2 and 4.8), this printing technology brought Catlin’s images to a wide audience.

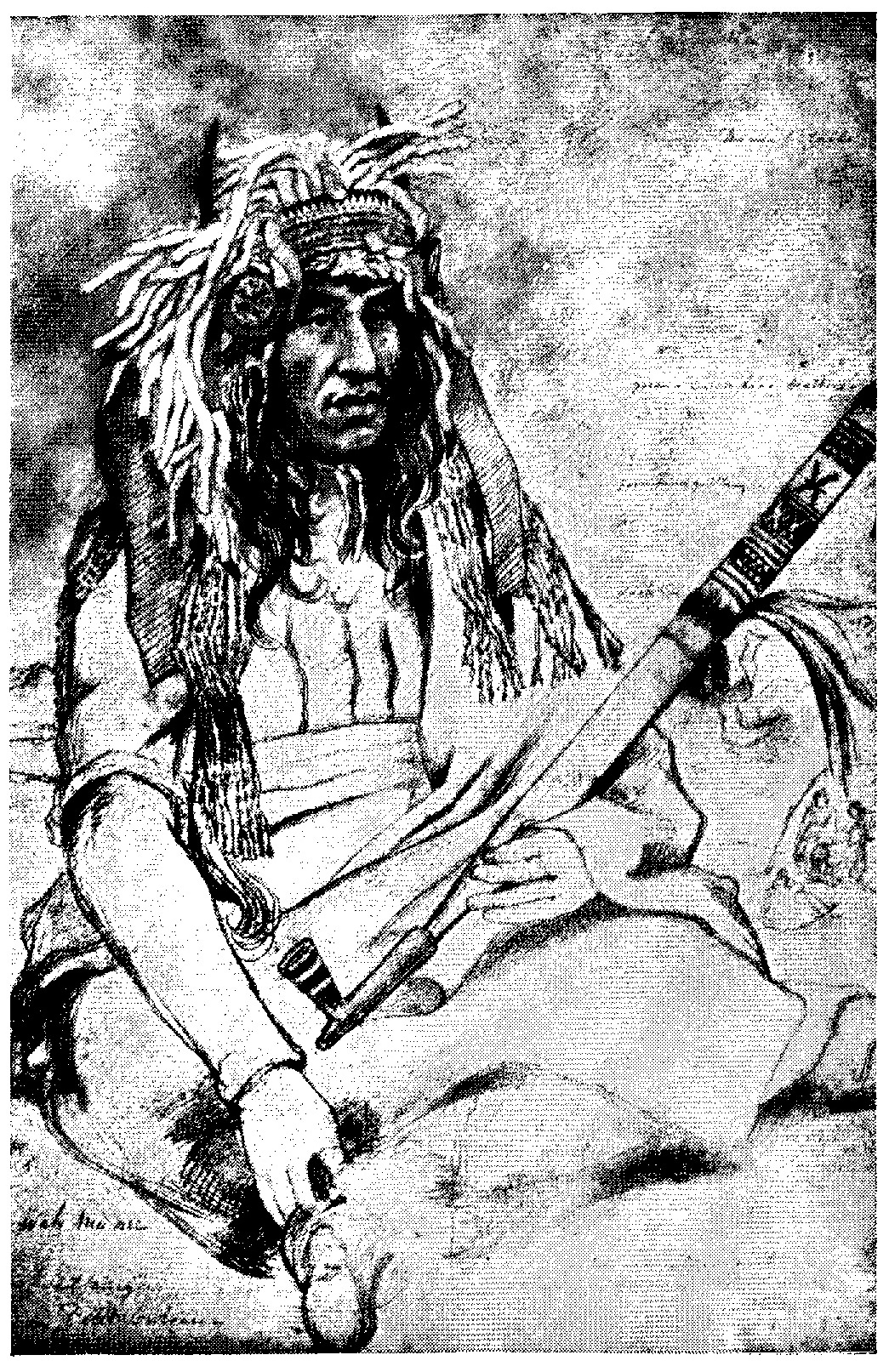

Part of Catlin’s self-promotion was the idea that he was completely at home with, and accepted by, the tribes he pictured. A portrait by William Fiske shows Catlin dressed in fringed buckskin. (See figure 5.3.) Behind him, in the shadowed interior of the tipi where he works, is a handsome Plains warrior with a female companion. This portrait implies an identification between the artist Catlin and his Indigenous subjects. The red pigment on the brush Catlin holds alludes to his role as the painter of the “red man.” Ironically, Fiske’s portrait of Catlin reveals the tension between the living reality and the objectification of Indigenous peoples that took place in the act of painting them. While the couple behind Catlin assert their own claims on the viewer, they remain in shadows. Literally, they are portrayed as secondary to the white artist who will, through images, speak for them. Thus, this portrait endorses Catlin’s voice appropriation.

The fur trade and exploration brought not only artists and trade goods but contagious disease. In terms of the Mandan, at least, Catlin unwittingly realized his intention of documenting “a dying race.” The same year that Catlin launched his traveling exhibition, the Mandan tribe that he had painted with such dignity were ravaged by smallpox, unwittingly introduced on a visiting steamship. The Mandan population was reduced from some 1600 to 125 people in just a few weeks.

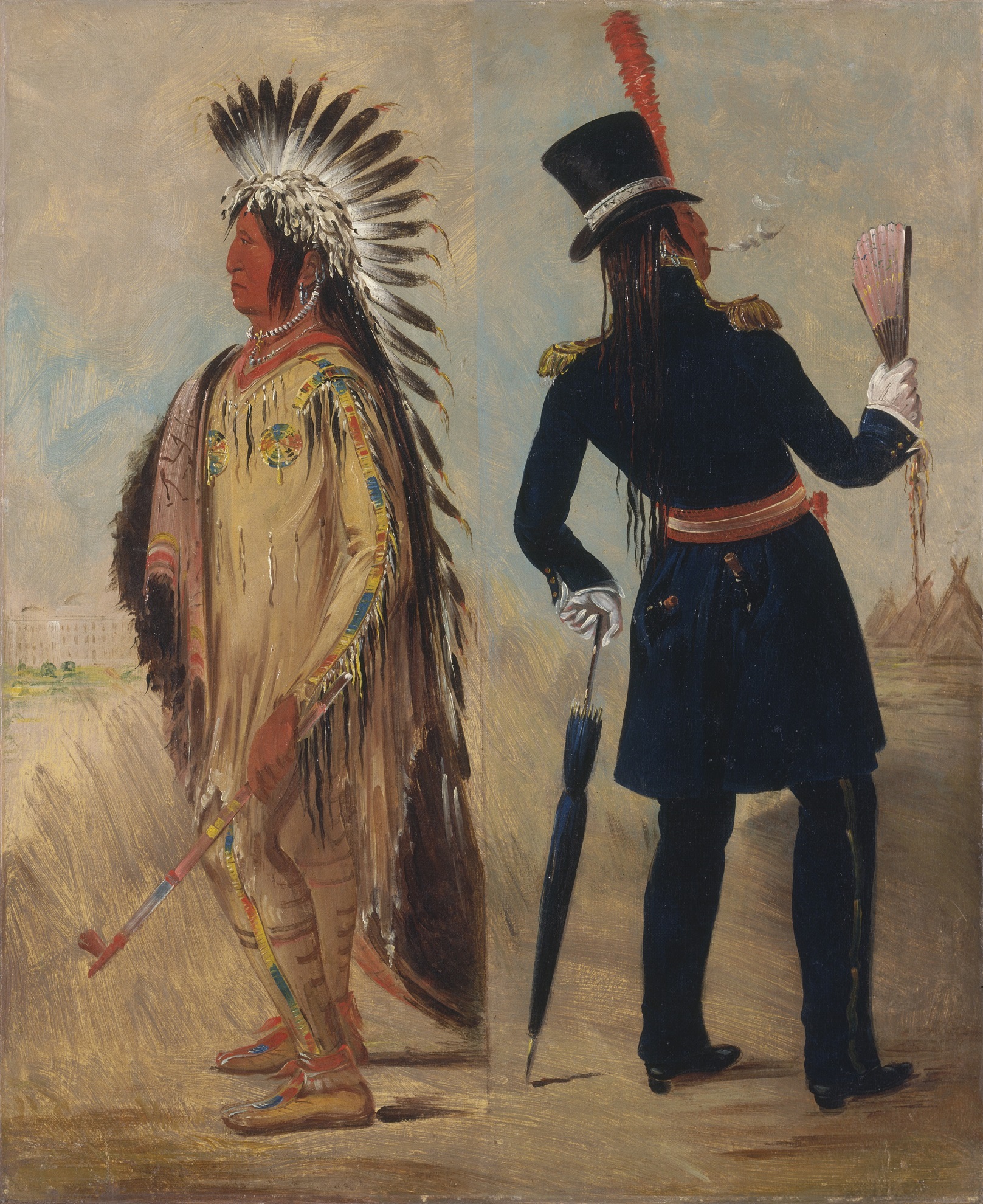

Increasingly for Catlin and his audiences, there was no middle ground of productive encounter between cultures. Instead, the dominant culture saw only a stark polarity between the Indigenous peoples in a noble state of nature, and the assimilated few who were irredeemably corrupted, or destroyed by contact with white society. Nowhere is this polarity more starkly presented than in Catlin’s Wi-jún-jon (Pigeon’s Egg Head) Going to and Returning from Washington. (See figure 5.4). Catlin’s two-part composition compares the splendid dignity of the handsome Assiniboine man on a trip to the nation’s capital city (seen in the background) with the strutting vanity of the dandified Wi-jún-jon following his return from Washington.

The before-and-after format contrasts every detail: the ceremonial peace pipe versus the civilized vice of the cigarette; the dignified pose appropriated from Classical statues as opposed to the returning swagger; the stoic bearing contrasted with the self-satisfied attitude. Lastly, the buffalo hide painted with the exploits of the warrior stands in striking contrast to the so-called “civilized” man: white gloves, umbrella, and fan. At the time, most viewer see these details as feminine artifacts that clash with his masculine military wear: an officer’s coat with epaulets and sash. (In the print version, Catlin adds a dangling sword to his outfit.) The result is that Wi-jún-jon has become a figure of ridicule. His empty symbols of military status stand in sorry contrast to traditions of Plains warriors. Completing this portrait of corruption are two whiskey flasks stashed in Wi-jún-jon’s pockets. Catlin’s Letter and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians contains a chart of paired terms contrasting the original and the corrupted warrior: the “pure” man was “free,” “graceful,” “clean,” “independent,” and “happy.” Following contact with white cultures, he was corrupted and “enslaved,” “graceless,” “filthy,” “dependent,” and “miserable” (Catlin 1857, p. 792). As far as Catlin was concerned, the frontier, at the boundary between the two ways of life, was already contaminated, so Catlin searched for subject matter farther west, presumably beyond the taint of contact with whites.

The tale of Wi-jún-jon had a sad conclusion. On his return home, his stories of the great populated cities to the east were rejected as lies by his people. Those who had not seen for themselves these cities, with their towering stone buildings and grand boulevards, could not imagine that so many white people existed. They responded with resentment and suspicion, eventually killing and scalping Wi-Jun-Jon. For Catlin, who had himself come under suspicion of fabricating his paintings and lying about his experiences, Wi-jún-jon’s misfortune had personal significance, revealing the dangers of standing between two cultures.

5.3. Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans

Two years after Catlin started to document Indigenous peoples, but a full ten years before he assembled his traveling “museum,” a book appeared that taught generations of Americans how to think about “the North American Indian” (Cooper 1985, p. 473). The book is James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, published in 1826. Within a year, the book was so popular that Thomas Cole took advantage of the story’s location in upstate New York and produced a painting of one of its key scenes. Although Cooper probably had no firsthand knowledge of Indigenous people, the content and voice appropriations of this book make it one of the most consequential artworks of the 19th century. Like Uncle Tom’s Cabin in relation to Southern life (see Chapter 4, Section 4.8), The Last of the Mohicans taught generations of Americans how to think about its Indigenous population. To offer one example, the book’s message set the stage for Catlin’s sales pitch that the people of the Plains were “a dying race.”

The Last of the Mohicans could not be clearer about its central message. The next-to-last sentence is a voice appropriation in which Tamenund, an Indigenous elder, offers his response to the events of the story: “The pale-faces are masters of the earth, and the time of the red-men has not yet come again” (Cooper 1985, p. 877). Given his status in the story, Tamenund is clearly meant to speak for the whole people. He proclaims that the colonial settlers are now “masters” of North America. The Indigenous people admit defeat. As one historian has recently observed, “This convenient fantasy could be seen as quaint at best if it were not for its deadly staying power” (Dunbar-Ortiz 2014, p. 104).

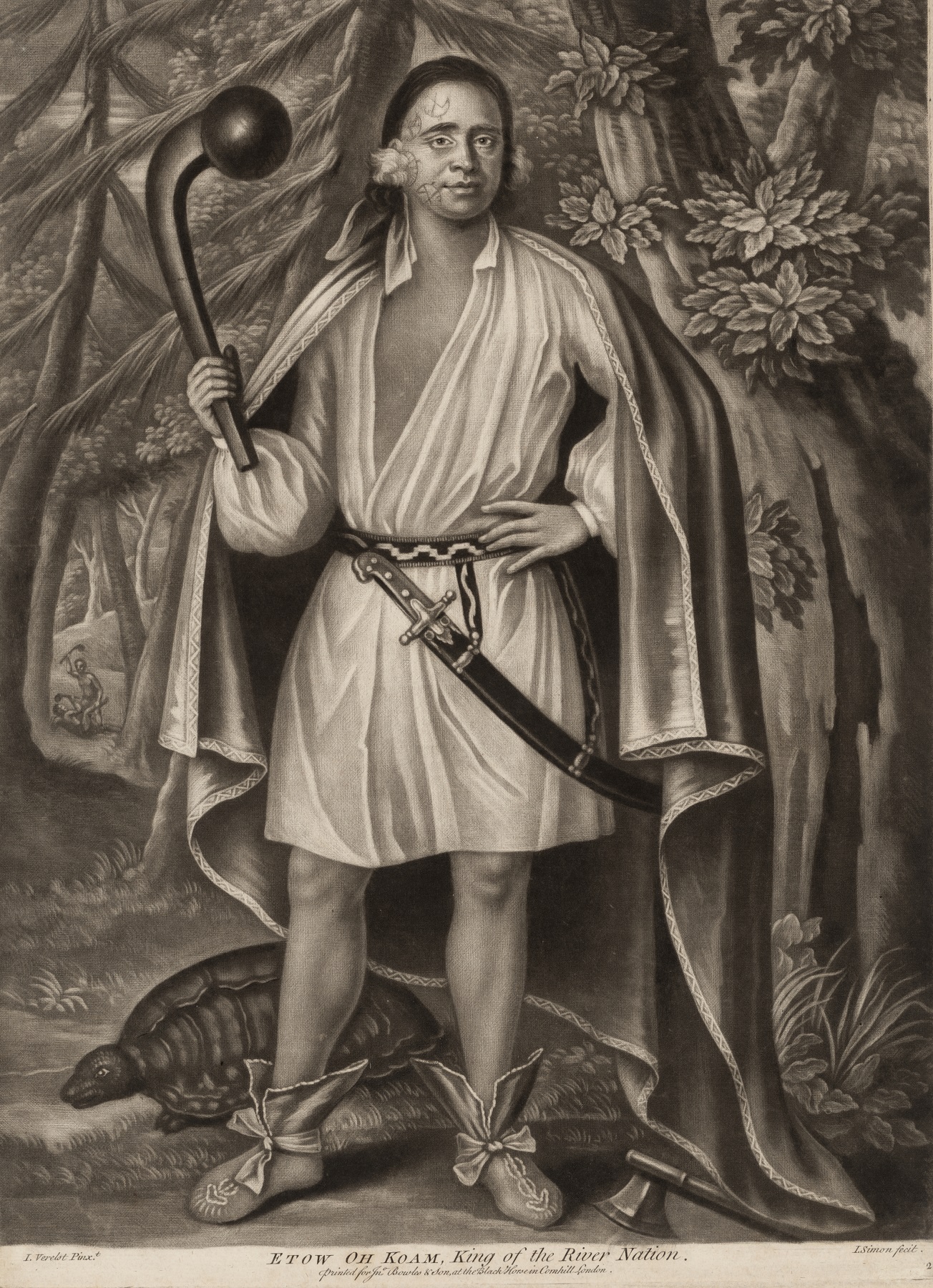

Cooper’s novel is built around real historical events of 1757, the mid-point of the so-called French and Indian War (1754-1763). Not yet separated from Great Britain, American militia joined British military forces against the French. France was colonizing the land that would become Canada, but there was an ongoing dispute about the border. The British recruited Indigenous allies from the Iroquois-speaking people. The French found allies among their rivals, the Algonquin-speaking people, including the Mohican tribe. (This name is a simplification of the correct name, Muh-he-con-neok.) Eventually, the Mohicans switched sides to join the British, and this alignment is in place in The Last of the Mohicans. (For a portrait of an actual Mohican warrior in 1710, see figure 5.5.)

The book’s title refers to its fictional claim that Uncas, the youngest of the main characters, is “the last” because his people have so inter-married with frontier settlers that his future wife and children will be, at best, half-Mohican. Given that this idea is highlighted in the title, the issue of racial identity is clearly intended to be an organizing theme. Direct reference to Uncas as the “last of the Mohican” occurs twice, as bookends to the story of Uncas. First, it is in the passage where readers are introduced to the young warrior. The second time is the book’s final paragraph. He has just been buried. In each case, the words are spoken by a tribal elder: Chingachgook, Uncas’ father, and then Tamenund, a spiritual leader. These are classic examples of voice appropriation, placing the dominant White culture’s concerns about racial identity into the mouths of people who did not categorize humanity in this same way. The English, rather than Indigenous peoples, opposed inter-marriage on the part of settlers. The French, in contrast, had no such opposition to intermarriage (Voyageur 2016). Cooper reflects the fact that English culture is highly conscious of race. On more than one occasion he has his hero, Hawk-eye, make remarks such as “I am genuine white” (Cooper 1985, p. 502). One of Cooper’s distortions of history is that he then projects this same concern for racial classification into the belief system of Chingachgook and Tamenund — the very people who are targets of colonial English prejudice. By doing so, he employs voice appropriation to suggest that Indigenous peoples do not blame the dominant culture for their mistreatment. In Cooper’s fictional world, Indigenous defeat and social collapse are the natural outcomes of racial difference.

It should be noted that, writing in the 1820s, Cooper uses the term “race” with two distinct meanings. As noted in Chapter 2 (Section 2.2), the word “race” had an unstable meaning in the later 18th century and early 19th century. In his Introduction to the book, Cooper uses the word to mark off all Indigenous people as one race (Cooper 1985, p. 473). But then there are several passages in which the White hero, Hawk-eye, treats each tribe as a distinct race with different racial characteristics (Cooper 1985, pp. 505, 511). It is not clear that anyone in 1757 would have used “race” as Cooper uses it here. As a result, The Last of the Mohicans contains an anachronistic voice appropriation, putting later ideas into the words of a fictional character in an earlier historical frame. One of the consequences is that 19th century readers would be reassured that their own assumptions about race were traditional and natural.

One aspect of this racial theme is to divide “the savage” (Cooper 1985, pp. 487, 488, 490, etc.) into two types. (Recall that at this time the word “savage” meant wild or untamed, and indicated a lack of civilization or culture.) Indigenous people who aid the White settlers and military are “noble” (Cooper 1985, p. 695). But for those who support the French enemy, Cooper engages in motif appropriation and brings in one of the oldest European signifiers of animalistic status: they resort to cannibalism by drinking the blood of those they kill in battle (Cooper 1985, p. 672). Observing such atrocities, Hawk-eye explains it in racial terms: “‘Twould have been a cruel and an unhuman act for a white-skin; but ’tis the gift and natur’ of an Indian” (Cooper 1985, p. 628).

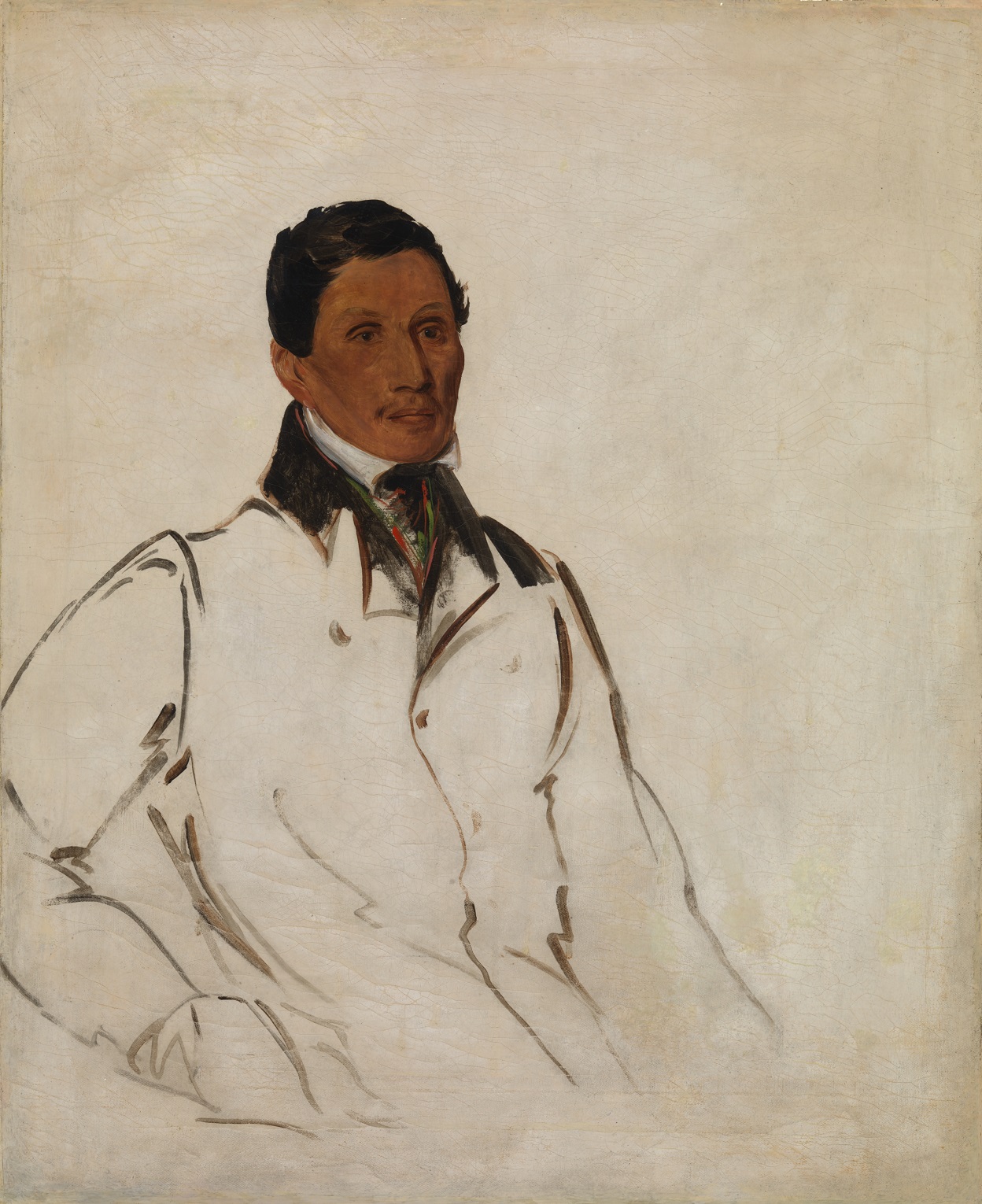

Cooper’s book has had the historical effect of making many people think that he is reporting historical fact and that the Mohican tribe ceased to exist before the Revolutionary War. That is not so. At the very time that Cooper was writing his novel, The Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Tribe was in the process of selling the last remnant of their ancestral lands and moving west of the frontier. Waun-naw-con (John W. Quinney), a tribal leader, negotiated purchase of new land in Wisconsin, and some of the tribe still lives there today. (See figure 5.6.) So much for the idea that the last Mohican died in 1757. As an interesting side note, historians think that Waun-naw-con was the first person to ever use the phrase “Native American.” He was a respected Christian missionary and was invited to give a 4th of July address delivered to a mainly White audience in 1854 (Hochbruck 1992, pp. 157-62). He started the speech by calling attention to common beliefs and stereotypes, including the myth of Indigenous “extinction.” He then rejected the dominant culture’s narrative of Manifest Destiny. He reminded the audience that they stood on stolen land. Calling for justice, he predicting that the Indigenous population of the country would live on, hoping that someday the dominant culture would realize that God’s justice demanded they pay for the nation’s “wrongs” and “crimes” against Native Americans.

5.4. Manufacturing “A Dying Race” and “Vanishing” People

As discussed in Chapter 4, the Indian Removal policies set in place by Andrew Jackson, president from 1828 to 1836, created ethnic cleansing of Indigenous peoples east of the Mississippi. This included the notorious 1838 “Trail of Tears,” the forced removal of settled agrarian Cherokee people from Georgia. The next step was displacement of the remaining Indigenous peoples of the Southeast in order to create the plantations of the Cotton Belt. At the same time, settlers pushed the frontier beyond the so-called “Old Northwest” (the upper Great Lakes).

However, these “removal” policies had the effect of creating decades of ongoing frontier conflict as new waves of settlers entered Indigenous lands.

For most Easterners looking westward, coexistence with Indigenous peoples was out of the question. Central to the ideology of white expansion into the West was the idea of wilderness: an image of the West as a space void of culture, empty and ready to receive civilization. The idea of wilderness was actively promoted by those who invested in the future of the West as a region that would replicate the institutions and culture of the original 13 colonies. In the view of White Christians, wilderness was the world that Adam and Eve encountered when they were driven from Eden. Wilderness was nature that was not yet tamed or altered by human activity. By viewing the West as an empty wilderness, Americans denied the possibility that White settler-colonization would displace a genuine culture. In the context of these deeply rooted assumptions, Indigenous people of the West were confronted as obstacle, or as the threatening “savages” of The Last of the Mohicans and other stories.

Much art of the period portrays westward expansion as an inevitable tide of civilizing institutions. As seen above in The Last of the Mohicans, one of the core ideas was that racial difference explained cultural dominance. In this manner the disappearance of Indigenous peoples could be explained as byproduct of progress rather than the result of active removal and genocide conducted by the dominant culture. In this sense, art served as propaganda that supported a political program of removal of dehumanized Indigenous people. Art and popular art that dealt with the West was designed to make the dominant culture comfortable with denial of the rights and sovereignty of Indigenous people.

For example, consider the views of the essayist and poet Henry David Thoreau. Like many of his time, he was directly influenced by reading The Last of the Mohicans. Thoreau was inspired to study Indigenous people in the Northeast before they vanished. To this end, he compiled a large manuscript on the topic of the Indigenous people, but most of this material remained in notebooks until after his death. Some of the material appeared during his lifetime in his book The Maine Woods, which develops the theme that “the Indian’s history [is] the history of his extinction” (Thoreau 1864, p. 5). Much of his knowledge of the Maine woods was content appropriation gained from his friendship with two men of the Penobscot Tribe, Joe Aitteon and Joe Polis.

Despite such friendships, Thoreau’s basic view was not especially progressive and is summarized in this journal passage: “Who can doubt this essential and innate difference between man and man, when he considers a whole race, like the Indian, inevitably and resignedly passing away in spite of our efforts to Christianize and educate them? . . . Everybody notices that the Indian retains his habits wonderfully, — is still the same man that the discoverers found. The fact is, the history of the white man is a history of improvement, that of the red man a history of fixed habits of stagnation” (Thoreau, vol. 10, pp. 251-52). Thoreau is voicing an idea that reappears again and again throughout the 19th century: the Indigenous peoples of North America are a distinct “race” with habits and behaviors so “fixed” by “instinct” that they cannot change. They remain as they were centuries earlier. So, they cannot be assimilated into a European-based society.

But there is something more to notice about the passage. Thoreau sneaks in a bit of voice appropriation in order to reassure himself that this is not simply a rationalization on the part of the dominant culture. Speaking for Indigenous people, he tells us that they are aware of, and “resigned” to, their fate. They will vanish, and they accept it.

These ideas are, of course, nonsense. For example, the People of the Seven Council Fires (The Oceti Sakowin Oyate) originally occupied the Ohio Valley and land around the Great Lakes, far from the Great Plains. (Collectively, these seven tribes are known as the Sioux, but that name is a French corruption of an name given to them by Ojibwa speakers.) The Oceti Sakowin people include the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota tribes. They migrated west in the 17th century to avoid conflict with the five Iroquois-speaking tribes. The Iroquois Nation, in turn, had been driven out of present-day New York by European settlers. The Oceti Sakowin people were, in the words of one historian, “a superbly flexible people” (Hamalainen 2019, p. 2). In a short time, they gave up much of their established way of life and developed another. Moving onto the plains, they amassed herds of horses and became expert marksmen who based their new life around buffalo hunting. (See figure5.7.) Their war craft, weapons, and riding were adapted from European sources. They traded to get guns and ammunition. Their horses were descended from ones brought to Mexico by Spanish invaders. Defending their new territory, they famously led the coalition that defeated U.S. troops at the Little Bighorn River in 1876. Ironically, the land that the Oceti Sakowin people settled was not their ancestral home, and yet the United States named it for on of the seven tribes: the Dakota Territory. The Dakota and other Oceti Sakowin people had arrived there only a few decades after the English arrived in New England.

Despite evidence to the contrary, misleading beliefs about a “fixed” and doomed “race” were spread by widely circulated images of Indigenous people in postures of noble resignation and tragic defeat. By the 1850s, the dominant culture was losing interest in portraits of proud, living Indigenous people. They preferred images such as Thomas Crawford’s The Indian: The Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization (See figure 5.8.). Crawford made several copies of his design. The earliest version is sculpted into the U.S. Capitol as part of the larger Progress of Civilization sculpture. (It is above the entrance to the U.S. Senate wing of the building.) By literally placing the dying man within a celebration of American progress, the message is explicit: the country’s progress is incompatible with its Indigenous peoples.

Crawford’s design is one among many similar statues. They were frequently placed in prominent locations in public buildings. For example, Peter Stephenson’s large marble statue of The Wounded Indian was displayed for a hundred years in Boston’s Mechanics Hall, one of Boston’s largest and busiest auditoriums. (See figure 5.9.) In this case, the man holds an arrow that he has just pulled from his chest. As with the death of Uncas in The Last of the Mohicans, competition among Indigenous peoples is offered as the source of their problems. As historian Jeff Fynn-Paul puts it, “What the Europeans did in the New World was insert themselves into a fluid power struggle which had been ongoing for millennia” (Fynn-Paul 2020). From this perspective, the dominant culture is symbolically off the hook. The problem of a declining Indigenous population is presented as an outcome of the inherent violence of Indigenous life, rather than frictions, disease, and deaths caused by European settler-colonialism.

Statues and pictures such as these communicated multiple ideas. They became an emblem of America’s difference from Europe, but also of virtuous attachment to nature. These images also encouraged nostalgic regret for what had been lost in the rise to continental empire. By locating Indigenous people in America’s past (and not the present), the dominant culture could avoid the true situation, which was that most of the continent continued to be lawfully occupied by Indigenous people. This artistic myth of the vanishing people made the majority population comfortable with land appropriation by shifting the blame from themselves to impersonal historical and biological forces.

The theme of the vanishing race also become popular in music, with many popular songs based on it. Some were even written for use in minstrel shows, so that a dominant culture fantasy about Indigenous people was integrated with an entertainment form that stereotyped and denigrated Black people. (See Chapter 4, Section 4.7.)

An example of such a song in minstrel shows is “The Indian Warrior’s Grave” (1850), by Marshall S. Pike. Like many of the popular “plantation” songs, Pike’s song pursues nostalgia by contrasting a happy childhood with the present time. The first verse is as follows:

Green is the grave by the dashing river,

Where sleeps the brave with his arrows and quiver,

Where in his prime, he roved in his childhood

Fought he and died in the depths of the wildwood.

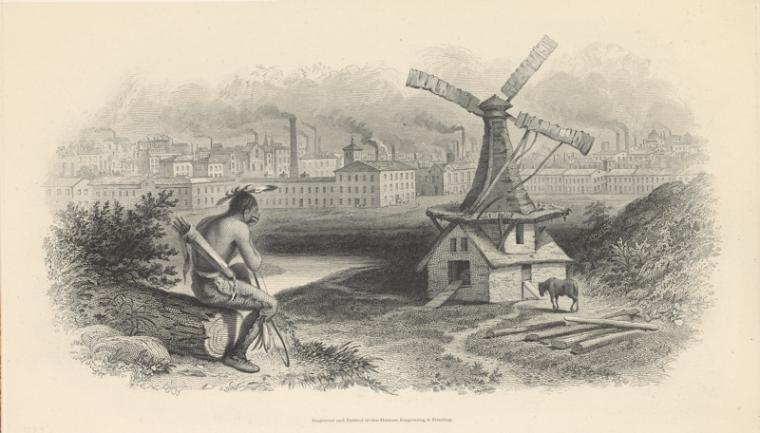

As explicitly confirmed by the full title of Crawford’s statue (The Indian: The Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization), the theme of defeated and isolated Indigenous men symbolized American progress. In many of these images, the warrior gazes out from his wilderness at factories, farms, and tilled fields. This vision of defeat in the face of a rising empire appeared everywhere from bank note engravings (See figure 5.10.) to John Gast’s very popular image of American Progress, which was widely seen in print versions. (See figure 5.11).

American Progress continues the tradition of an allegorical female personification of America. However, she is no longer an Indigenous woman. She has become a white woman, Columbia (a feminization of “Columbus” first used in 1738). During this era, one of the most popular songs in the U.S. was “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean,” a patriotic appropriation of the British song “Britannia, the Pride of the Ocean.”

The racial dimension of Columbia was made explicit in the following verse of Phillis Wheatley’s poem, “His Excellency General Washington,” written in 1775 amid growing expectation of the American Revolution.

One century scarce perform’d its destined round,

When Gallic powers Columbia’s fury found;

And so may you, whoever dares disgrace

The land of freedom’s heaven-defended race!

Ironically, Wheatley was an enslaved Black woman who achieved fame for her poetry. In this case, she praises the American Revolution by connecting the conflict with George Washington’s military service in the French and Indian War. Wheatley’s reference to a “heaven-defended race” of Anglo-Saxon colonials conveniently deletes Mohican and other Indigenous allies from her historical reconstruction. Wheatley promises future defeat to anyone who “dares disgrace” Columbia’s claim to the land to the west of the thirteen colonies. By referencing the earlier conflict in this manner, the poem says that colonial powers are granted the land by “heaven” and the resulting “land of freedom” means freedom for the dominant culture. In a nutshell, Wheatley’s four lines summarize the core principles of Manifest Destiny many years before anyone put a name to that doctrine.

In Gast’s image, Columbia is moving westward, guiding settlers who come in increasing numbers as the railroads cross the continent. The scene in the lower right confirms that her mission is to secure land for farmers. This mission means driving out the buffalo, and with them, the Plains tribes (here personified by one family who retreat ahead of the white settlers). But eventually, there would be nowhere else to go. The unstated message was that the entire continent was a “land of freedom” (for the right people) and the tribes must either assimilate (like Pocahontas) or in some other way vanish, as had the tribes who had lived on the East Coast during the early colonial period.

5.5. Revisiting Landscapes and Manifest Destiny

Chapter 4 explored the origins and spread of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, that is, the idea that the “race” of “Anglo-Saxons” is the source of the only legitimate dominant culture for America, and that this God-given status justified the seizure of land from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The historical record of the slave trade and the long-standing mistreatment of the Indigenous peoples confirm that the doctrine of Manifest Destiny was a byproduct rather than the source of systemic racism in the United States. However, it justified new waves of mistreatment and new land grabs that included extension of the United States into significant areas of territory where the dominant culture had been, until then, Hispanic.

The Hudson River School of painting appropriated European artistic innovations and adapted them to build ideas about Manifest Destiny into American landscapes. Here, we find that style and motif appropriation in visual art supported the country’s appropriation of land. As the reference to the Hudson River indicates, they started in New York State. However, as the United States moved into the West, the next generation of American landscape painters combined the symbolism of Manifest Destiny with the myth of the vanishing, vanquished people. This complex symbolism is not always apparent to 21st-century viewers of these paintings.

Two different kinds of symbolism were used to signal Indigenous irrelevance and extinction. First, there was the strategy of creating massive, sublime landscapes in which there are no people. Second, when Western landscapes do show signs of the presence of Indigenous people, they routinely suggest that they are a migratory people. Either way, 19th-century artworks presented Indigenous peoples as a vanishing race in order to soothe White guilt about “the mendacity, exploitation and the violence involved in dispossessing Indians of their land” (Fulford 2006, p. 202).

An important example of the first type – where there is no sign of human existence — is Thomas Moran’s The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. (See figure 5.12.) It is one among a series of images that led to the establishment of Yellowstone National Park, the first national park, in 1872. To understand that the absence of people is an innovation made for symbolic reasons, compare these later works with Thomas Cole’s View from Mount Holyoke. (See Chapter 4, figure 4.3.) Cole set up his painting as a contrast between settlement and wilderness, but he inserts a human figure (himself) into the wilderness portion. Since the early Renaissance, artists had been taught that the best way to indicate size and scale is to have a human figure in the picture. By inserting himself as a tiny figure in View from Mount Holyoke, Cole conveys the power of nature and the challenge of securing the wilderness in the name of American progress.

It is difficult to convey how radical it was for American artists to portray nature as a place where there was no human presence. Historically, European landscapes were backgrounds in pictures of people. Landscape became more common as the main feature of some paintings around the time that Columbus sailed for the Americas, but almost every landscape that was given public display showed some human activity. If there were no actual people in the image, there were signs of human presence, such as ruined buildings, a bridge over a river, or domesticated sheep or cows. Although Moran breaks free from this European tradition, a comparison of Cole and Moran shows that he is engaged in style appropriation from both Cole and, before him, J.M.W. Turner. (See Chapter 4, Section 4.4.) So, Moran established continuity with recent landscape painting while also innovating.

In The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, the absence of human figures or presence symbolizes that the land is vacant wilderness, un-owned by anyone and newly discovered. So, images of this type are throwbacks to the doctrine of discovery, symbolically justifying American possession of the land. (See also Chapter 3.) As art historian Scott Manning Stevens puts it, these paintings of “discovery” are a “seductive blinding and erasure of the history of the land itself” (quoted in Weinberg 2022). The history Stevens references is, of course, the historical fact that this land was Indigenous land. Parallel to the actual tangible appropriation of the land that was underway, Moran’s painting justifies expansion into the West through its symbolic appropriation of a newly discovered wilderness.

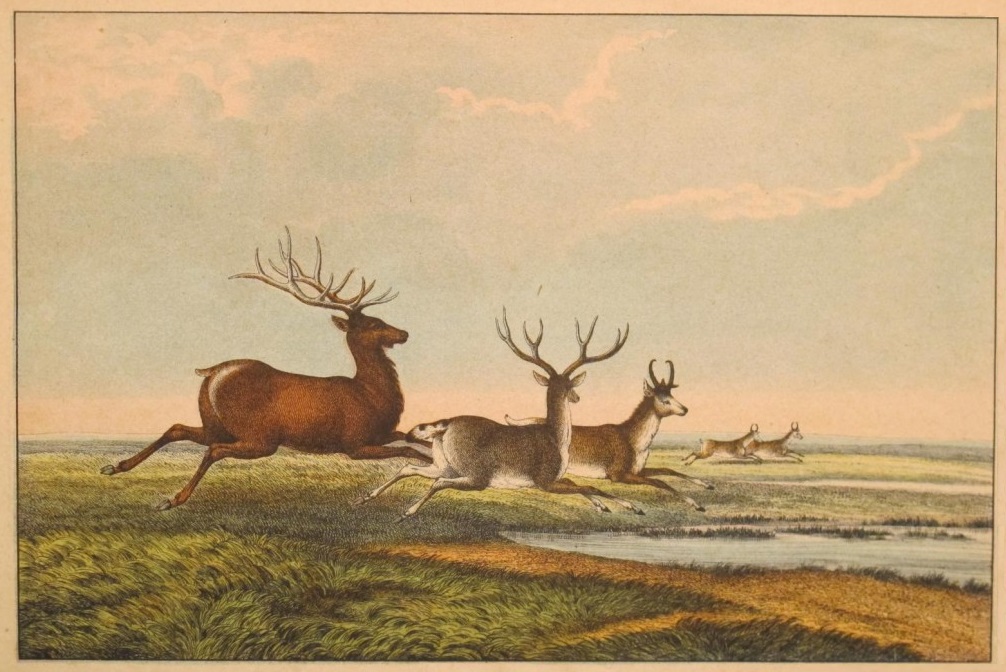

However, most of the West was not the filled with the “purple mountains majesty” celebrated in the song “America the Beautiful.” Artists had a harder time dealing with the land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. The area consists largely of flat, unbroken plains. Artists did not find much here that fit their training regarding what was beautiful, picturesque, or sublime. Buyers, likewise, were not interested in buying pictures of empty, flat landscapes. (The one major exception was pictures of bison hunting.) In the decades following the Railroad Act and the Homestead Act (both 1862) , the development of a network of railroads brought European immigrant settlers. Many were given free title to up to 160 acres of land if they would break the sod and farm it. For artists, one way to relieve the monotony of the flat grassland and to make it appear attractive was to foreground game animals. (See figure 5.13).

Again, the picture symbolically appropriates the land by presenting it as unoccupied. Pictures such as this were significant for their appeal to potential European immigrants: the land is ripe for grain crops that the railroads would carry east for sale. This myth of the empty, fertile plains became central to the self-image of the so-called “pioneers” who occupied and farmed this land. The idea permeates the writings of Willa Cather, a celebrated author who wrote about the immigrant experience in Nebraska. Several of her novels explore the clash between the dominant culture and new immigrant settlers in the 1880s. Because the land had recently been cleared of Indigenous people through their removal to the Oklahoma and Dakota territories, Cather adopts the immigrant perspective of being the first people to ever live there. Because they did not leave behind roads and buildings, the people just removed from the area were no more significant than “prehistoric races” (Cather 1913, p. 19). Cather personifies the soil of the prairie as “eagerly” wanting to be broken, plowed, and planted, suggesting that the land itself was happy now that farmers replaced Indigenous people.

Excerpts from Willa Cather, O Pioneers!

The roads were but faint tracks in the grass, and the fields were scarcely noticeable. The record of the plow was insignificant, like the feeble scratches on stone left by prehistoric races, so indeterminate that they may, after all, be only the markings of glaciers, and not a record of human strivings. …

The rich soil yields heavy harvests; the dry, bracing climate and the smoothness of the land make labor easy for men and beasts. There are few scenes more gratifying than a spring plowing in that country, where the furrows of a single field often lie a mile in length, and the brown earth, with such a strong, clean smell, and such a power of growth and fertility in it, yields itself eagerly to the plow; rolls away from the shear, not even dimming the brightness of the metal, with a soft, deep sigh of happiness. …

Alexandra hummed an old Swedish hymn, and Emil wondered why his sister looked so happy. Her face was so radiant that he felt shy about asking her. For the first time, perhaps, since that land emerged from the waters of geologic ages, a human face was set toward it with love and yearning. It seemed beautiful to her, rich and strong and glorious. Her eyes drank in the breadth of it, until her tears blinded her. Then the Genius of the Divide, the great, free spirit which breathes across it, must have bent lower than it ever bent to a human will before. The history of every country begins in the heart of a man or a woman.

The second strategy of minimizing the territorial rights of Indigenous people can be seen in Albert Bierstadt’s enormous painting of Lander’s Peak, in the Rocky Mountains. (See figure 5.14.) A viewer who is not aware of the background doctrine of Manifest Destiny might think that it confirms the land rights of Indigenous peoples. However, that is not how it was intended to be understood, nor how it was actually understood. A contemporary critical analysis of the painting stressed the presence of “the faithful and elaborate delineation of the Indian village, a form of life now rapidly disappearing from the earth,” which made it “a historical landscape” (quoted in Burns and Davis 2009, p. 507). Bierstadt’s inclusion of this “rude savage human life” is intended to convey the absence of “civilization.”

Viewed through the lens of Manifest Destiny, the Shoshoni encampment presents a historical people, that is, a people of the past rather than the present or future. (Recall that Lewis and Clark believed that Sakagawea was Shoshoni.) Just as Cole’s View from Mount Holyoke divides into two contrasting halves, so does Bierstadt’s canvas. However, instead of contrasting right and left sides, Bierstadt creates a contrast between the upper and lower halves of the image. Understood in terms of the widespread view that Indigenous peoples were a “dying race,” the upper half offers the sublimity of the mountains, while the Shoshoni presence in the lower half creates a picturesque nostalgia for a lost way of life. Ironically, Bierstadt used his sketches of Lander’s Peak to create a second version of the same scene, this one containing no signs of human presence.

Understood in its day as a history painting, Bierstadt’s The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak presents a false history. The Shoshoni people had not placed encampments in the valley pictured here until about the time the painting was made. They had primarily occupied the open plains just to the east, but had been forced up against and into the Rocky Mountains by the arrival of the U.S. military in 1859. Colonel Frederick Lander, the namesake of the peak, organized this westward removal of the Shoshoni people, who were compensated through payment in horses, guns, and ammunition (Coutant 1899, p. 364).

5.6. Indigenous Dwellings: The Tipi

The practice of picturing Indigenous people as temporary occupants of the land became more common after the Civil War. The railroads were beginning to cross the plains and increasing numbers of people were moving west. Following removal of almost all Indigenous peoples to land west of the Mississippi, from 1851 onward the U.S. Government took increasingly harsh steps to deprive Indigenous people of territory on the Plains and throughout the West. From 1851 to 1887, this involved moving Indigenous peoples onto reservations. They were confined to relatively small areas and were deprived of the right to roam freely or otherwise occupy other land, which the government opened to settlers for farming and grazing.

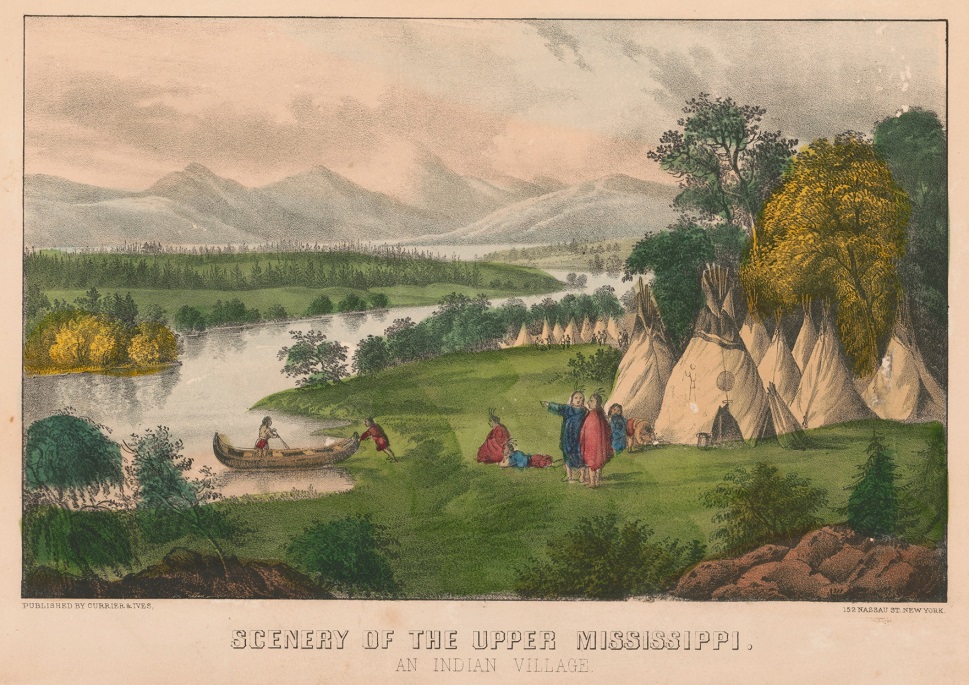

The idea that all Indigenous peoples could be moved to land selected by the government was supported by one of the most widespread motif appropriations in American art. Once Catlin and others brought back images of Indigenous settlements on the Great Plains, the tipi (or teepee) became the stereotype of Indigenous life. (Examine the right side of Catlin’s much-reproduced image of Wi-jún-jon, figure 5.4 above, and note that he is pictured as returning to a group of tipis.) The term “tipi” is a shortened form of the Lakota word for a pointed dwelling, and other Plains tribes had other names for the same structure (Gobal 2007, p. 9).

Historically, the tipi originated to shelter people who were hunting the migratory bison herds of the Great Plains. Even at the height of their use, they were basically unknown east of the Mississippi River and west of the Rocky Mountains. (See figure 5.15.) There is reason to believe that they originated among the Lakota people after they moved west from the Ohio Valley, which would indicate that they only came into use in the later part of the 17the century. Thus, their use was limited to about two centuries of time in less than a quarter of the land of the 48 contiguous states. Tipis required transportation by horses, which again confirms that they were not in use before the middle of the 17th century.

Excerpt from Luther Standing Bear: My People, the Sioux

Our home life began in the tipi. It was there we were born, and we loved our home. A tipi would probably seem queer to a white child, but if you ever have a chance to live in one you will find it very comfortable — that is, if you get a real tipi; not the [canvas] kind used by the moving-picture companies. When I was a boy all my tribe used tipis made of buffalo skins. Some were large; others were quite small; depending upon the wealth of the owner. In my boyhood days a man counted his wealth by the number of horses he owned. If a tipi was large it took a great many poles to set it up; and that called for a great many horses to move it about when camp was broken. A small tipi required about twelve poles to set up, and they were not very long, so that only about two horses were required when on the move. But a large tipi required from twenty-five to twenty-seven poles, and it was necessary that they be quite a bit longer. It required about six horses to transport properly a large tipi when camp was broken. We were at liberty to move any time we chose. So, if a man wanted a large tipi, he must first be sure he had horses enough to move it.

For 300 years, artists had correctly shown that various Indigenous groups had several types of permanent housing. (See above, figure 5.2, and see Chapter 3, figure 3.10.) This included visual documentation that the very same tribes who used tipis when hunting bison on the open plains also built permanent villages with houses. Seth Eastman sketched just such a village in the area that is currently St. Paul, Minnesota. (See figure 5.16.)

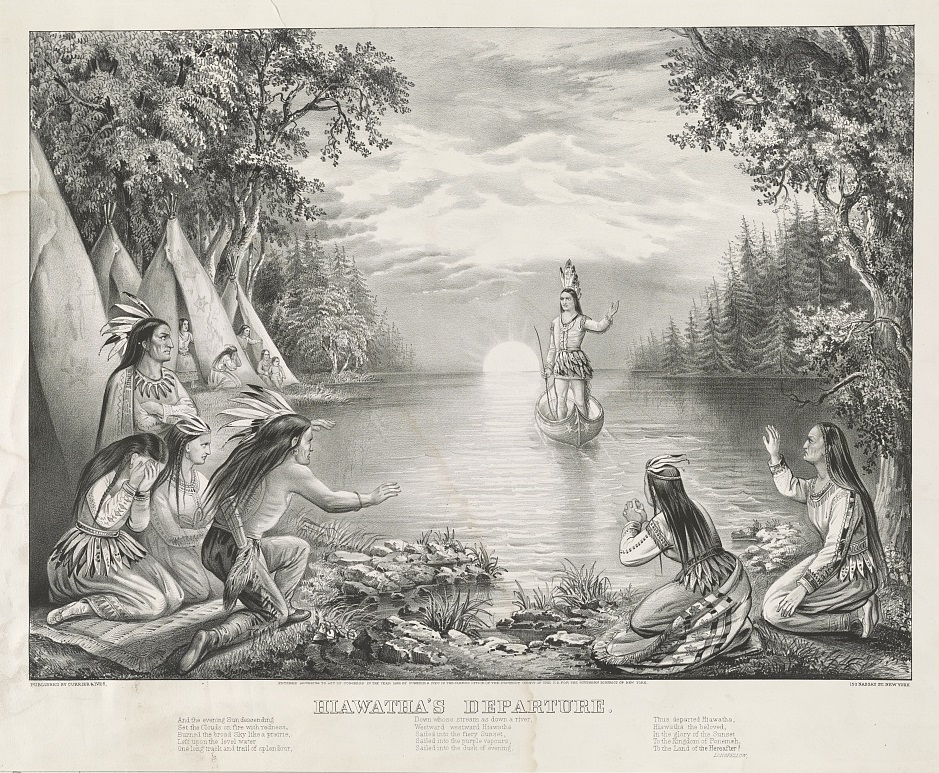

However, many artists did not care about accuracy. This was especially the case when their goal was to communicate popular stories to the general American public. The tipi was a striking and distinctive design, with no real equivalent in the dominant culture. Because it was different and distinctive, artists could use it as a visual shortcut to indicate that they were picturing Indigenous people. With the exception of the occasional image of the brick and stone houses of the Hopi people, images of other kinds of Indigenous dwellings became scarce. Artists inserted them into images without regard to geographical setting. For example, tipis were assigned to woodland peoples who did not have horses to move them, and illustrations of The Song of Hiawatha routinely included tipis. (See figures 5.17 and 5.18. Note the lack of poles to hold up the walls in the first image.)

Like The Last of the Mohicans, The Song of Hiawatha was set in a romanticized, fictionalized past. By replacing Ojibwa wigwams and longhouses with tipis, it was easier for the dominant culture to imagine the characters as migratory people, and so not a people with a land-right based on European-style land development. In actual fact, Hiawatha’s traditional Ojibwa society had permanent settlements and they planted crops such as beans and squash (Fulford 2006, p. 16). A reflective reader might realize that the story of the corn god, Mondamin, meant that the Ojibwa had settled agriculture (see Chapter 4, Section 4.9), but the pictures override this detail.

Once tipis were popularized in 19th-century illustrations, they also made their way into illustrations of events in American history where they did not belong. For example, Felix Octavius Carr Darley was a popular 19th-century book illustrator. Creating an illustration of a scene from Massachusetts history that took place around the year 1650, Darley inserts standard tipis from the Great Plains into a forest group. (See figure 5.19, right side.) Again, an artist has falsified history though motif appropriation, suggesting impermanence and mobility for a people who had no means to move heavy tipis. The image shows Darley preaching Christianity to Algonquian-speaking communities near the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In reality, Darley normally preached indoors, often in wigwams. The wigwams of the Algonquian-speaking people had rounded roofs and looked nothing like tipis. Besides the motif appropriation of placing tipis on the right side of the picture, Darley has engaged in a second artistic motif appropriation, giving Eliot a hand gesture associated with John the Baptist.

It is easy to see why artists falsified history by inserting tipis in pictures where they did not belong. It functioned as a universal symbol of Indian-ness. However, the practice had two unfortunate effects. First, the practice erased group differences. Different Indigenous peoples had distinct cultures, including distinctive architecture. The lazy use of pictures of tipis suggests, wrongly, that all Indigenous people in North America are basically the same. Second, it falsely suggests that all Indigenous peoples were nomadic hunters, like the Lakota and other tribes of the Oceti Sakowin people. Since tipis conveyed the message that Indigenous peoples never created permanent settlements, these images reassured the dominant culture that Indigenous people were uncivilized and made no claim to land ownership. Appropriation of the tipi as a standardized symbol of Indigenous life was another ongoing justification of the tangible appropriation of land.

5.7. Images of “Savages,” Faceless and Otherwise

Until recently, it was extremely common to refer to Indigenous people as “savages.” It communicated people who were not Christian and who had not advanced to civilized life. The term is used to refer to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from the time of first encounters. It appears in the journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and in both The Last of the Mohicans and The Song of Hiawatha. However, those two books were popular expressions of the idea of a “noble” but vanishing race. Over the course of the 19th century, the word came to be reserved for the contrasting category of Indigenous peoples who refused to cooperate, assimilate, and yield their land. Images of noble dying warriors were now contrasted with ones that emphasized a lack of nobility. Frederic Remington is one of the most popular artists to focus on the West, and his only statue of the head of an Indigenous man is called “The Savage.” (See figure 5.20.) No one thinks this is an attractive or positive portrait. Bronze copies of it are still manufactured and sold today.

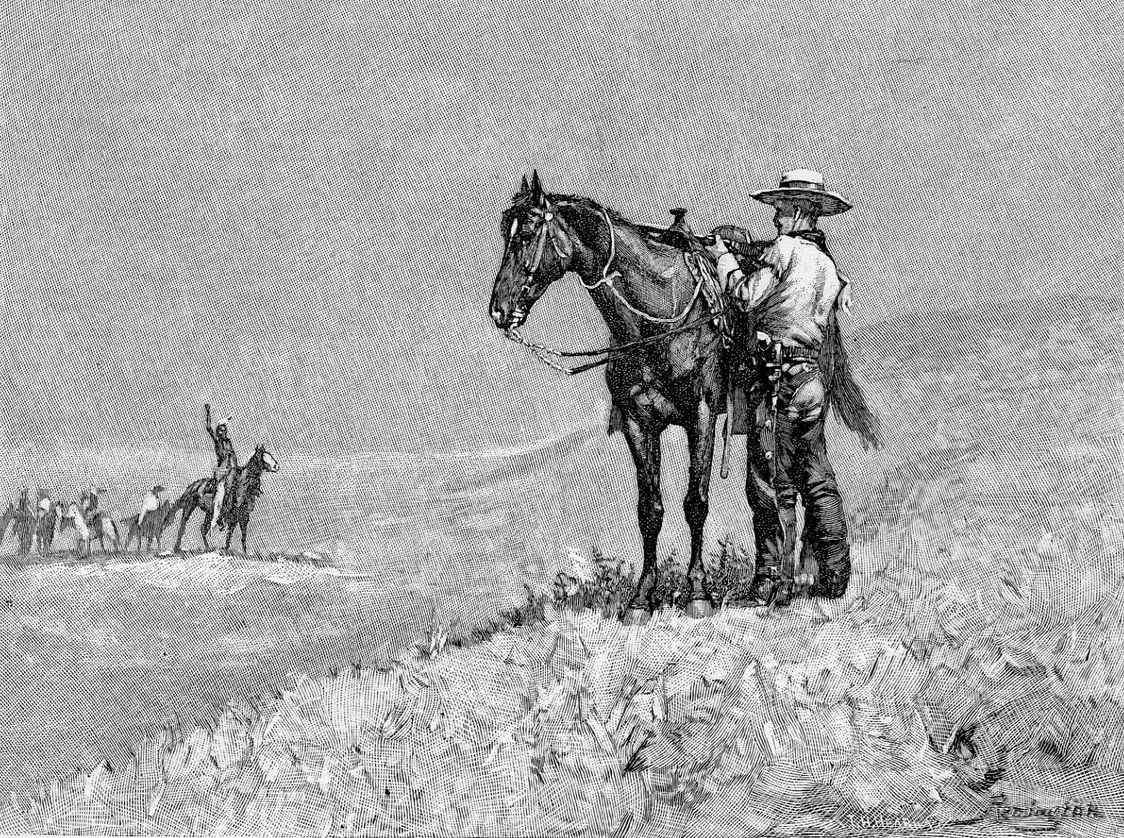

Remington made numerous images of the West, most often glorifying cowboys and the U.S. Military fighting to secure the Western frontier. Many of these reached a mass audience when reproductions were regularly featured in the magazine Collier’s Weekly. In almost all cases, Indigenous people are shown attacking, or threatening to attack, settlers and the military. The scenes are constructed as the reverse of the myth of the vanishing people. In Remington’s world, White people are always outnumbered and threatened. As one critic explains, “Usually he showed a small party of men – five or six at the outside – facing overwhelming odds” and “confronting death without a hint of fear” (Dippie 1994, p. 40) (See figure 5.21.) Typically, the attackers are kept at a distance, or not shown at all. In Remington’s world, they are generally faceless, and so they are not equivalent to the White fighters who are cast as defenders, dying in support of Manifest Destiny.

Some of Remington’s images present situations that modern viewers might read as non-threatening or peaceful. However, that is not how they were understood by the dominant culture of his time. For example, the illustration “Standing Off Indians” was produced to accompany a magazine article by future-President Theodore Roosevelt. (See figure 5.22.) Without the title or story, it might look like an encounter in which a cowboy watches a group of mounted men pass by. However, “standing off” refers to a situation of mutual threat. Looking closely at the picture, one will notice that the nearer figure is readying his rifle. In the text it illustrates, Roosevelt relates the one and only time he encountered Indigenous people outside of a White settlement. He says that while the Indigenous people of the western Dakotas are defeated and generally “meek and peaceable,” there is always the problem of “meeting a band of young bucks in lonely, uninhabited country” (Roosevelt 1888, p. 102). He tells us that he encountered such a group one day in open country, and they immediately drove their horses toward him in attack mode, “whooping.” He stood behind his horse and used its back to steady his rifle, took aim at the leading horse, and “like magic” they scattered. One unarmed man tried to approach him, but Roosevelt made it clear with gestures that he would fire if he did so, and they all left. (This attempted approach appears to be the scene in Remington’s drawing.) Roosevelt’s self-advertisement in popular magazine stories such as this were part of a public relations campaign after he returned East and entered politics. Clearly, the story and accompanying illustration accepts and supports the dominant culture’s fear that Indigenous people are natural killers and must never be trusted.

Remington was not alone in producing this kind of “Western” art. One popular competitor was Charles Scheyvogel. His work is less known today because he died relatively young, so he produced fewer images. At the same time, some of Scheyvogel’s art is more overt about the idea that Manifest Destiny was a racial project. This is clearly the case in the painting In Safe Hands, where Scheyvogel appropriates Remington’s theme of heroic cavalrymen while building the image around the rescue of a little girl with blond hair. (See figure 5.23.) Notice, also, the wagon train surrounded by Indigenous warriors on horseback. If the meaning is not clear, it is spelled out in the title of another of Scheyvogel’s images of the cavalry defending a wagon train against attacking warriors: Protecting the Emigrants. These are not simply images of frontier conflict. They are images supporting the conflict because it secures White settlement of Indigenous lands.

5.8. Photographs as Voice Appropriation

Until now, few of the images shown and discussed have been photographs. Without going into detail about the history of cameras and photography in the 19th century, it is important to understand that early photographs could not be reproduced. Each exposure created one and only one photo. Therefore, individual photographs made prior to the Civil War were not reproduced and had limited impact on the general public. Technology permitting multiple copies from the same negative became more common around 1850. New chemical processes also shortened the exposure time, simplifying the process of taking photos. However, mass-production remained complicated for most of the 19th century. Drawings, not photographs, remained the basis of the overwhelming majority of mass-produced images until the 20th century. One famous exception is a photograph of the whip scars inflicted on a formerly enslaved Black man, published in Harper’s Weekly in 1863. (See Chapter 2, figure 2.6.)

One might think that once photography became common, people would get to see genuine, unfiltered documentation of Indigenous life. However, that is not really the case. Photographers often select scenes that conform to standard views on the subject of the photo. Consequently, many of the early documentary photographs of Indigenous peoples — including some of the most famous and widely circulated images — continued to support and justify Manifest Destiny and the myth of the vanishing race.

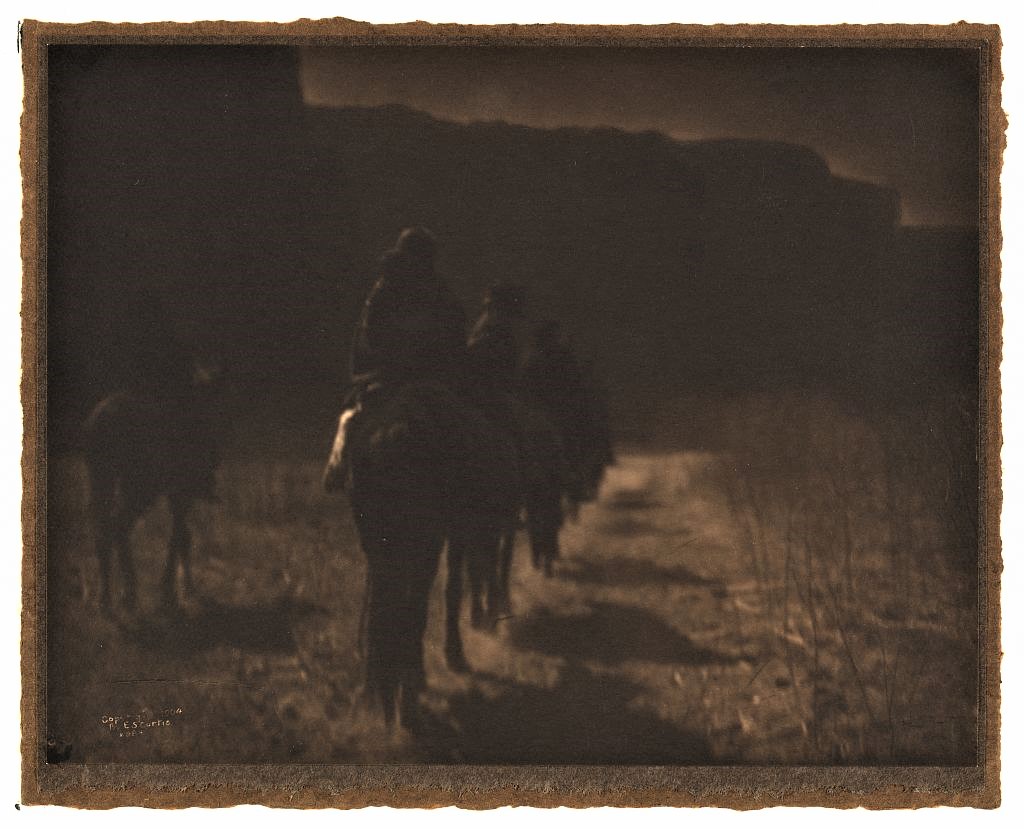

The most famous set of such images are the thousands of photos created by Edward S. Curtis to document more than 80 distinct Indigenous groups. However, Curtis started the project in 1900, at which point few Indigenous people in the United States lived the “traditional” life of their ancestors. Backed by wealthy patrons, Curtis set out to find and document people who “still retained to a considerable degree their primitive customs and traditions” (quoted in Library of Congress). In practice, this meant getting people to wear ceremonial clothing. As a result, the people in many of Curtis’ photos are not dressed the way Indigenous people dressed on an everyday basis. Sometimes, Curtis lent them horses, clothing, and weapons and other props. When he was not creating an individual portrait, Curtis carefully arranged and staged a scene to fit his view of Indigenous life. For example, the very first image in the first book he published is called “The Vanishing Race.” (See figure 5.24.) It was staged at dusk because, Curtis said, he wanted to suggest that the whole “race” is “passing into the darkness of an unknown future” (quoted in Kennedy 2001, p. 14).

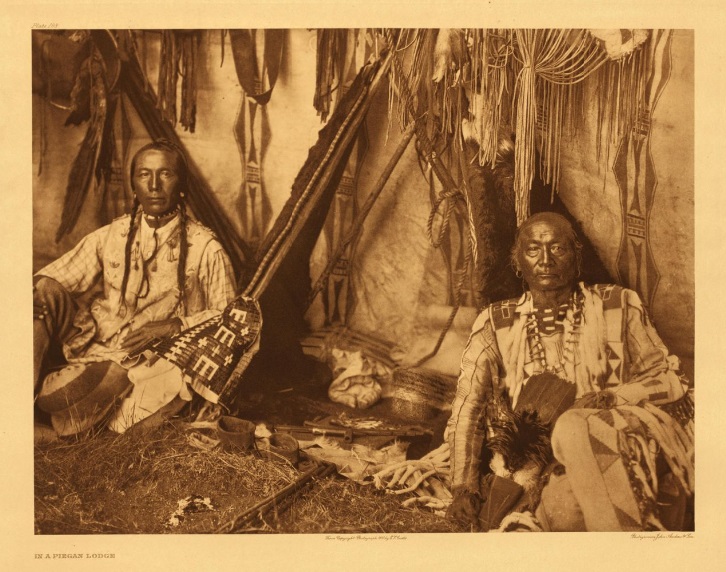

Curtis sometimes altered the photographs. In particular, he removed evidence that he was documenting people in the early 20th century. Like so many before him, he wanted to show Indigenous people as dwelling in the historical past. In one case, he removed a modern clock that was sitting on the ground between two men. (See figure 5.25, a “doctored” photo.)

Curtis spent most of his life doing a great service to Indigenous peoples, and everyone featured in Curtis’ pictures willingly cooperated. However, in his pursuit of timeless images, he ignored the living culture of reservation life and the harms done by forced assimilation. His falsification of their lives in pursuit of his goals is a kind of voice appropriation in which the participants are used to communicate ideas that had long appeased the dominant culture. Curtis’ photographs are, like so much of the art of the frontier, another confirmation of The Last of the Mohicans.