6 Content Appropriation: A Deeper Look

Theodore Gracyk

Chapter Goals

- Define content appropriation

- Define exoticism

- Understand how content appropriation has supported racism

- Define dominant culture ally

- Explore failures of allyship

- Explore examples of successful allyship

- Define dialogism in relation to appropriation

- Understand how dialogism can challenge racism

6.1. Content Appropriation: Reviewing the Basics

This chapter goes into more detail about content appropriation. It discusses ways in which it has supported racism in the United States. But it also examines ways in which content appropriation has be used to challenge the dominant culture.

Content appropriation and voice appropriation are distinct forms of cultural appropriation. In practice, however, they are frequently bundled together. To summarize the difference, content appropriation occurs when someone presents information that is drawn from another source. In this sense, our lives are full of content appropriation. People constantly share information that they did not originate. The focus of this book is appropriation within the arts, where appropriated information or content is often encoded in an appropriated story or image. Content appropriation is cultural appropriation when the material originated in, and was taken from, a different culture. Voice appropriation is similar, but it is characterized by the way that the material claims to offer insight into the worldview and belief system of another culture. This is most often done by portraying representative members of another culture, so the beliefs and values of selected individuals stand for those of the whole group. (For a more detailed discussion, see Chapter 1, Sections 1.6 and 1.8.)

In practice, content appropriation can be separated from voice appropriation by removing all references to the originating culture. This process is common in the contemporary world of mass entertainment, especially film-making and television.

- The Broadway musical West Side Story (1957) and subsequent hit film (1961) are updates of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. New York City of the 1950s replaces 15th-century Verona, Italy.

- Other Americanized updates of Shakespeare include the film 10 Things I Hate About You (1999) and Anne Tyler’s novel Vinegar Girl (2016). Both are appropriations of The Taming of the Shrew.

- 12 Monkeys (1995) is a remake of the French experimental film La Jetée (1962) that thoroughly Americanizes it.

- The Departed (2006) is a remake of the Hong Kong film Infernal Affairs (2002), replacing the Chinese criminal syndicate of the original with an Irish Mafia gang in Boston.

- The Spanish television series La casa de papel (2017) was purged of all Spanish content when re-tooled as Money Heist: Korea – Joint Economic Area (2022).

- The popular television series The Office (2005–13) Americanized the British original (2001–3) of the same name.

By removing all references to the cultures that created the original content, these acts of thematic and narrative appropriation are free from voice appropriation. This method of appropriation supports the common but doubtful claim that art aims to express universal truths about the human condition.

However, a great deal of content appropriation is not disguised. Cultural origins are frequently highlighted rather than hidden. Audience awareness of cultural appropriation can be part of the point of appropriating it. In such cases, the new material implicitly promises to inform about what is distinctively “foreign” — that is, strange and unusual — in the other culture. Display of cultural difference is a goal of appropriating the content, and therefore shapes the selection of the content. Examples of this kind of content appropriation were discussed in Chapter 5, with the documentary pictures of Indigenous Americans made by George Catlin and Edward S. Curtis. (For example, see figures 5.2 and 5.24.) Some writers give a more specific label to this kind of content appropriation: it is subject appropriation (Young 2010).

6.2. Exoticism

When cultural appropriation highlights what is different or unusual in another culture, it often promotes exoticism. Edward Said is well known for his study of a major type of European exoticism, Orientalism (Said 1978).

For many centuries, European art and popular art featured settings in “the Orient” (any and every society of the Middle East, Asia and the Far East). Said explores European literature to show how Orientalism constructed an imaginary and exotic “Orient.” This fad for Oriental content was well established by the late 18th century. For example, in the era when opera was popular music theater, two of Mozart’s operas are based on Orientalism: The Abduction from the Seraglio (1782) and The Magic Flute (1791). Their plots presuppose that there is a deep opposition between European and Oriental societies. But there is something more to Orientalism: the opposition of cultures is coupled with a racist assumption on the part of the European artist and audience that the Eastern “other” is racially — that is, naturally and unavoidably — inferior (Said 1978, pp. 41, 133, 313).

The problem is not confined to fictional works like operas and novels. It can occur in visual representations. Documentation is seldom a neutral activity. As explained in Chapters 3 and 5, documentation frequently functions in the service of a social and political agenda. Within the context of Orientalism, non-fictional content appropriation routinely emphasized how these lands and people were remarkable, mysterious, and “hopelessly” strange (Said 1978, pp. 1, 51, 166). (See the example of van Gogh in Chapter 1, Section 1.4.) For example, visual representations of women frequently found excuses to show them naked or minimally clothed, demonstrating the low moral standards of the Orient. (See figure 6.1.) (See also Chapter 3, figures 3.4 and 3.13, and the discussion of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly in Chapter 1, Section 1.8.)

Everything that Said says about Orientalism — European representation of the Orient — has strong parallels in patterns of American cultural appropriation. Content appropriation on the part of the dominant culture often aims at exoticism, highlighting cultural differences between a non-dominant group and the dominant culture (hooks 1992). Later examples in this chapter will suggest that content appropriation can also be used in a positive way. However, cultural appropriation frequently seeks the exotic by emphasizing what is (from the perspective of the dominant culture) remarkable and strange. In doing so, material that might be regarded as merely documentary should be understood as a method by which the dominant culture reinforces its distance from — and, implicitly, superiority over — a non-dominant group. (See figure 6.2.)

6.3. Misunderstood Intentions and Failed Allyship

There is a famous proverb, dating back to the Middle Ages, that says hell is full of well-meaning people. In the most common American version, the proverb says, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

When exoticism is an element of cultural appropriation, even the most sympathetic and fair-minded author or artist is likely to reinforce the prejudices of the dominant culture. As an example, consider two White authors — Mark Twain and Bret Harte — who reported on the California gold rush in the middle of the 19th century. Both authors called attention to the mistreatment of Chinese immigrants.

Gold was discovered in California in 1848, and it was found in an accessible form. It was present in the beds of the many rivers that carried melting snow down from the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The area had only recently been seized by the United States in a “local” uprising that was backed by the U.S. military. In 1848, the population profile was overwhelmingly Indigenous. Estimates of the Indigenous population range from 160,000 to 300,000. There were perhaps 6,000 Mexican Hispanics and fewer than 1,000 non-Hispanic White people. The gold rush brought about a rapid change: within two years, the population of the state may have doubled. While the majority of the new immigrants came from within the United States, it is estimated that one in three immigrants were men from China. To limit their competition with White gold seekers, “foreign” miners were heavily taxed. The tax had its desired effect: most of the Chinese immigrants turned to other forms of manual labor. San Francisco was the major port serving the mining boom, and many Chinese immigrants started businesses there, such as shops, laundries, and restaurants. Chinese immigration continued for thirty years, totaling 300,000 or more.

Two Americans who migrated to California later became famous authors: Mark Twain and Bret Harte. Both men started their writing careers there as newspaper writers. In 1864, Harte hired Twain as a writer for The Californian, a weekly publication edited by Harte. Both men later published books about their time in the mining camps. They both recognized that the Chinese community was of interest to readers back East, and they produced early examples of Orientalism in an American context. Of these, Harte’s was the more consequential.

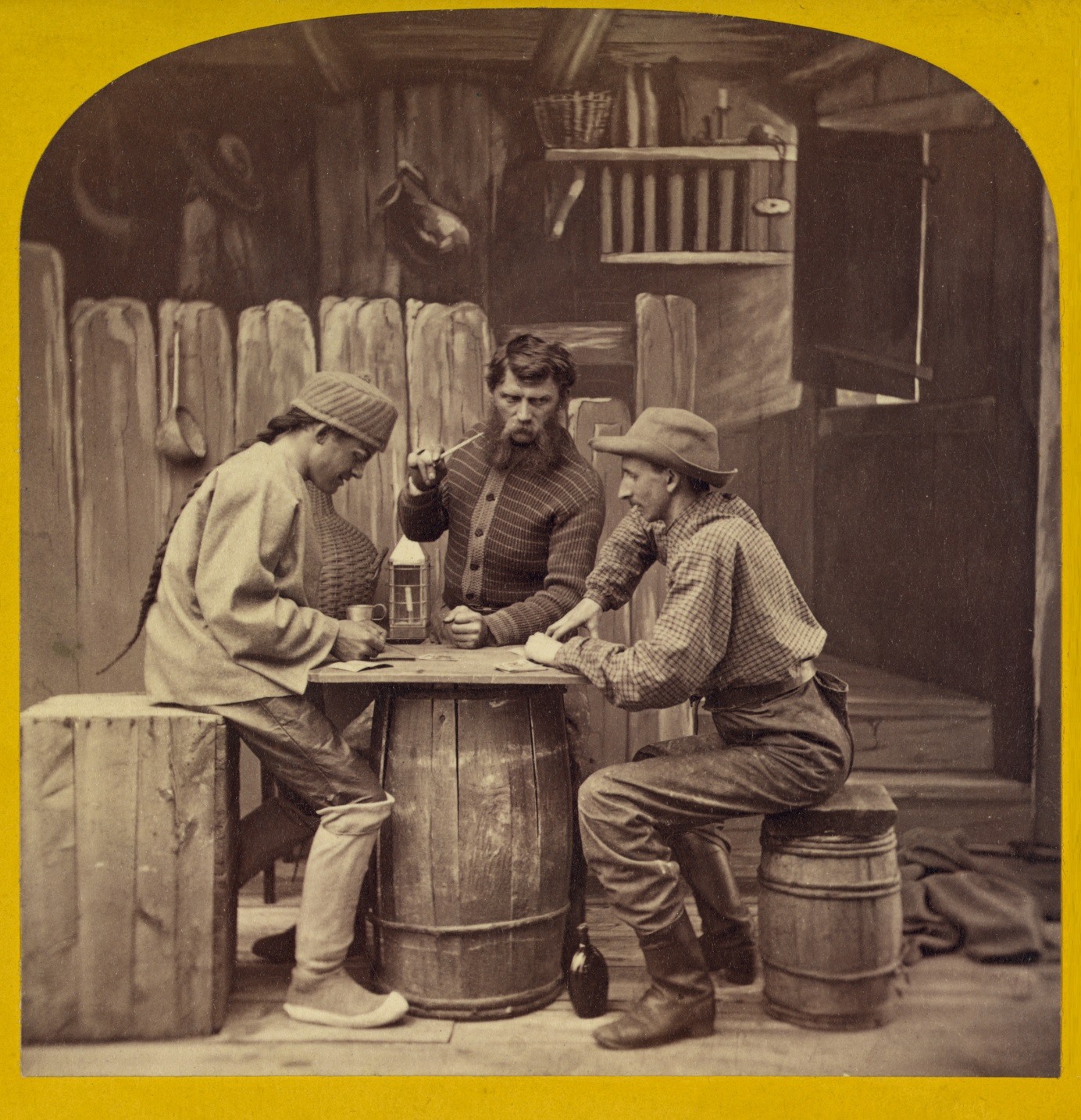

Both Twain and Harte respected the Chinese immigrants and tried to support them through their newspaper writings. Twain discussed their social status in relation to the class differences in the White population, emphasizing that the Chinese population was better educated and more civilized than the average White gold miner. Harte attempted to convey sympathy for the barriers facing Chinese immigrants by writing a satirical poem, “Plain Language from Truthful James” (1870). His poem was rapidly republished in newspapers throughout the United States, often with illustrations, using a title he did not supply, “The Heathen Chinee.” (See figures 6.3 and 6.4.) With that name, it was set to music and became a popular song. By the end of the year, Harte was one of the most famous and best paid writers in the United States.

Excerpt from Mark Twain, Roughing It

Of course there was a large Chinese population in … every town and city on the Pacific coast. They are a harmless race when white men either let them alone or treat them no worse than dogs; in fact they are almost entirely harmless anyhow, for they seldom think of resenting the vilest insults or the cruelest injuries. They are quiet, peaceable, tractable, free from drunkenness, and they are as industrious as the day is long. A disorderly Chinaman is rare, and a lazy one does not exist. So long as a Chinaman has strength to use his hands he needs no support from anybody; white men often complain of want of work, but a Chinaman offers no such complaint; he always manages to find something to do. He is a great convenience to everybody—even to the worst class of white men, for he bears the most of their sins, suffering fines for their petty thefts, imprisonment for their robberies, and death for their murders. Any white man can swear a Chinaman’s life away in the courts, but no Chinaman can testify against a white man. Ours is the “land of the free”—nobody denies that—nobody challenges it. (Maybe it is because we won’t let other people testify.) As I write, news comes that in broad daylight in San Francisco, some boys have stoned an inoffensive Chinaman to death, and that although a large crowd witnessed the shameful deed, no one interfered. …

Accompanied by a fellow reporter, we made a trip through our Chinese quarter the other night. The Chinese have built their portion of the city to suit themselves; and as they keep neither carriages nor wagons, their streets are not wide enough, as a general thing, to admit of the passage of vehicles. …

We ate chow-chow with chop-sticks in the celestial restaurants; our comrade chided the moon-eyed damsels in front of the houses for their want of feminine reserve; we received protecting Josh-lights from our hosts and “dickered” for a pagan God or two. Finally, we were impressed with the genius of a Chinese book-keeper; he figured up his accounts on a machine like a gridiron with buttons strung on its bars; the different rows represented units, tens, hundreds and thousands. He fingered them with incredible rapidity—in fact, he pushed them from place to place as fast as a musical professor’s fingers travel over the keys of a piano.

Bret Harte, Plain Language from Truthful James (1870)

Which I wish to remark,

And my language is plain,

That for ways that are dark

And for tricks that are vain,

The heathen Chinee is peculiar,

Which the same I would rise to explain.

Ah Sin was his name;

And I shall not deny,

In regard to the same,

What that name might imply;

But his smile it was pensive and childlike,

As I frequent remarked to Bill Nye. …

Which we had a small game,

And Ah Sin took a hand:

It was Euchre. The same

He did not understand;

But he smiled as he sat by the table,

With the smile that was childlike and bland.

Yet the cards they were stocked

In a way that I grieve,

And my feelings were shocked

At the state of Nye’s sleeve,

Which was stuffed full of aces and bowers,

And the same with intent to deceive.

But the hands that were played

By that heathen Chinee,

And the points that he made,

Were quite frightful to see,—

Till at last he put down a right bower,

Which the same Nye had dealt unto me.

Then I looked up at Nye,

And he gazed upon me;

And he rose with a sigh,

And said, “Can this be?

We are ruined by Chinese cheap labor,”—

And he went for that heathen Chinee.

In the scene that ensued

I did not take a hand,

But the floor it was strewed

Like the leaves on the strand

With the cards that Ah Sin had been hiding,

In the game “he did not understand.”

In his sleeves, which were long,

He had twenty-four packs,—

Which was coming it strong,

Yet I state but the facts; …

Which is why I remark,

And my language is plain,

That for ways that are dark

And for tricks that are vain,

The heathen Chinee is peculiar,—

Which the same I am free to maintain.

[Explanation: The men are playing the once-popular card game Euchre. The White men gamble with Ah Sin believing he “did not understand” the rules of Euchre. Five cards are dealt to each player and these are used in five rounds. The highest card laid down in each round wins the “trick.” A “bower” is a jack and it is the high card in the game of Eucher. The jacks are also ranked in case two are played in the same round. The highest jack is called the “right bower.” Ah Sin plays the same right bower that the narrator is holding in his hand, revealing that Ah Sin is cheating.]

There is a very small bit of voice appropriation in Twain’s description of the Chinese immigrants: “they seldom think of resenting” the injustices they suffer. Otherwise, these samples of their writing are examples of content appropriation.

Where Twain is direct in his support, Harte is more indirect. 19th-century readers would immediately understand “Bill Nye” to be an Irish name. Therefore, Harte tells a story featuring two immigrant groups who are in competition for unskilled jobs as manual laborers: “cheap labor.” This reading is supported by the fact that Harte had already raised the same issue in an editorial, observing that the “quickwitted, patient, obedient, and faithful” Chinese were “gradually deposing the Irish from their old, recognized positions in the ranks of labor” (quoted in Romeo 2006, p. 112). Harte is trying to make the point that Bill Nye and the “truthful” narrator are hypocrites. Ah Sin is not “peculiar” at all. Nye and Ah Sin are basically the same. Both have extra cards up their sleeves. Yet Ah Sin is physically assaulted by Nye as the narrator stands by and does nothing. The dominant culture permits Billy Nye to cheat Ah Sin — and, by implication, all Chinese immigrants — because Ah Sin and Bill Nye are held to different standards.

Harte’s poem is pure content appropriation. It contains no voice appropriation. Ah Sin does not speak and we are guided by the viewpoint of the White narrator. (Looking to cash in on the success of the poem, voice appropriation was added to the content appropriation when Harte co-wrote the play Ah Sin with Mark Twain in 1877.)

Despite his good intentions, Harte’s poem backfired. As such, it serves as a lesson why exoticism is dangerous even when it is meant to make a positive point. Harte tried to present the relative status of Chinese and Irish immigrants as a way of ridiculing the dominant culture’s racial prejudices. The dominant culture renamed the poem “The Heathen Chinee” and read it as confirmation of their anti-Chinese bias. In addition to finding the poem amusing, 19th-century Americans took it seriously as evidence that Chinese people are sneaky and deceitful competitors who do not play fair with other groups. The poem became a rallying cry of anti-Chinese racism, and it was even entered as evidence in Congress to support a ban on Chinese immigration (Lanzendorfer 2022).

Where the real-world reception of “Plain Language from Truthful James” diverged from Harte’s intentions, Twain’s documentation of Chinese immigration has problems, too. Twain was both a newspaper reporter and a humorist. As shown in the short excerpt from Roughing It, Twain played up exoticism, which tends to undercut his serious purpose. Like Harte, Twain emphasizes the hypocrisy of the dominant culture. Twain describes Chinese immigrants as a kind of model minority, and then suggests that, for that very reason, obstacles are created so that they will not succeed. At the same time, Twain is clearly working within — and so reinforcing — the racialized thinking of his times. He presupposes that cultural traits have a biological basis, and tries to defend Chinese immigration based on inherent, positive characteristics of their “race.”

Twain and Harte adopted the role of ally, which is “any member of a privileged or dominating group using their position to advocate for [a] nonprivileged, oppressed group” (Fried 2019, p. 447). Harte failed as an ally, and Twain had problems as one, too. Cases of this type illustrate Homi Bhabha’s warning, “We can never quite control [cultural appropriations] and their signification. They exceed intention” (Artforum 2017).

However, it would be a mistaken, hasty generalization to conclude that allyship cannot succeed through content appropriation. At best, these cases suggest that exoticism tends to work against allyship.

6.4. Successful Allyship: Winslow Homer

In contrast to Twain and Harte, Winslow Homer offers an example of successful allyship through content appropriation. Homer was a prominent visual artist of the 19th century. He got his start creating images of the Civil War, many of which were sketched at the front lines and then published in Harper’s Weekly Illustrated Magazine. After the war, he produced expensive art in the form of oil paintings, many of which were then adapted as black and white drawings and mass-produced as illustrations in Harper’s Weekly. This magazine was the most widely read publication in the United States during this time period. As a result, he became one of the best-known American artists of his time. The dominant culture embraced him as one of their own, and an early art critic went so far as to link him to an imagined Anglo-Saxon past: ““Like the men of Viking blood, he rises to his best estate in the stress of the hurricane” (Downes 1900, p. 106).

On the one hand, Homer’s significance is that he constructed a vision of the dominant culture that seems to celebrate a highly traditional version of White America. As the art critic Holland Cotter puts it, Homer made his fortune by producing what the audience wanted: “comforting visions of an imagined age of rural innocence” (Cotter 2013). For many in the dominant culture, he is the painter of the one-room schoolhouse, children playing snap the whip, New England fishermen hauling in their catch, and young men sailing for pleasure on a summer’s day. (See figure 6.5.)

On the other hand, Homer produced a body of work that is less celebratory about the United States. Shifting his focus away from the dominant culture, he used content appropriation to create a sharply critical form of social commentary. Across the span of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras that followed the Civil War, he produced a set of insightful and sympathetic images of Black American life. Given Homer’s position in the dominant culture, these are works of cultural appropriation. Shortly after his death, if not before, Homer’s content appropriations were recognized and applauded as positive acts of allyship. Furthermore, he designed images that avoided the misunderstanding and misuse that befell Harte’s poem about the Chinese immigrant, Ah Sin. One of Homer’s paintings, The Gulf Stream, is considered one of most significant of all American artworks. Before discussing that painting, two others deserve attention.

A Visit from the Old Mistress (1876) should be approached with the knowledge that Homer created it a decade after the Civil War and the legal abolishment of slavery. (See figure 6.6.) The White mistress, on the right, was once an enslaver of the other women in the picture, who are now emancipated.

Although the timing might be a coincidence, Homer created this image as the policies of Reconstruction were being rolled back. Reconstruction was the period of 12 years following the Civil War, during which the Federal Government took positive steps to secure the rights of formerly enslaved Black people. Withdrawing Federal troops and oversight from the South in 1877, the United States government would no longer protect Black Americans and guard their rights as equal citizens. In an essay about this painting, Sarah Senette summarizes Homer’s achievement.

In A Visit Form the Old Mistress, … the women look at each other as though staring across a battlefield. Their faces register a range of emotions, sadness, anger, and even resignation. … [the] group of African American women … appear rooted in place. … Far from expressing a new relationship that emerged after the Civil War, A Visit from the Old Mistress depicts an unfortunate continuity in the lives of formerly enslaved women in the American South and hints at the ultimate failure of Radical Reconstruction. … The fact that the African American women remained in close enough proximity to receive an informal visit from ‘the old mistress’ is particularly significant, as recently freed women often worked in the same spaces and performed the same services for white employers before and after the Civil War. … [T]he women of color appear poor, a fact that reflects African American women’s continued poverty after the Civil War and the failure of Reconstruction to fundamentally change living conditions for women of color. … Homer’s somber use of color, his bifurcated composition, and the cabin’s dreary interior … likely signifies both his observations and the continuing political, social, and economic reality of formerly enslaved women after the Civil War. (Senette 2015)

Given the timing, Homer’s Dressing for the Carnival of 1877 must also be understood as an exploration of race relations in America. (See figure 6.7.) It shows two women sewing a Harlequin costume onto a man while six children patiently watch. The image was created from sketches that Homer made of an emancipated Black family in Virginia. Black Americans with a Caribbean background had transferred aspects of their traditional pre-Lent carnival celebrations to the 4th of July. (Notice the small flag held by the boy on the right.) Like A Visit from the Old Mistress, this painting was made at the dawn of the Jim Crow era and the new system of legal segregation, and the painter likely intends that we should view it in those terms. Celebration of carnival is a Roman Catholic practice common in the Caribbean and New Orleans, but otherwise unknown in the Protestant South. As a consequence, the practice of dressing as a Harlequin was unusual even among Black Americans. To openly continue their traditions, carnival practitioners moved them to holidays that were supported by the Protestant White majority.

Given Homer’s decision to showcase an unusual Black Southern custom, Dressing for the Carnival is, to some extent, an example of exoticism. However, there is no condescension in Homer’s portrayal of this cultural practice. His interest in showing real people engaged in their lives stands in stark contrast to the ridiculous Black stereotypes of the ongoing minstrel tradition. (See Chapter 4, figures 4.9 through 4.12.) This is not to say that Homer was immune from the influence of that tradition. One early work, Defiance: Inviting a Shot Before Petersburg (1864), contains a number of figures. One of whom is a Black musician playing banjo who looks very much like a performer in a minstrel show. However, we do not find these stereotypes in the work Homer produced after the Civil War.

As with the two examples just discussed, Homer’s most important representations of Black life were oil paintings. Because they challenged familiar stereotypes, they were not reproduced in newspapers or magazines. Although they were not widely known during his lifetime, some White Southerners threatened him with violence for producing them (Downes 1911, pp. 85-86). Black audiences who could see these paintings on display in New York City responded positively to them. They were praised by Alain Locke, a prominent Black philosopher and art critic. Writing about Homer’s work 25 years after his death, Locke singled out one painting for special praise: “The Gulf Stream began the artistic emancipation of the Negro subject in American art,” possessing a degree of “human sympathy and understanding” not found in the work of any of Homer’s contemporaries (Locke 1936, p. 46).

Coming from such an influential Black writer, Locke’s praise is significant. Earlier, Section 6.3 introduced Jeremy Fried’s notion of dominant culture allyship. Expanding on that idea, Fried says that an artist must pass a basic test to qualify as genuine ally of a non-dominant group. The test “is acceptance by the relevant people and communities within the dominated group. … One becomes an ally by being identified as such by the community one aims to support” (Fried 2019, p. 452). Homer’s painting clearly passes this test due to Locke’s praise for it.

Strange Fruit

Another example of a genuine ally is Abel Meeropol and his 1937 poem, “Strange Fruit.” Written by a Russian-Jewish high school teacher in New York, the poem is a work of content appropriation that aimed to raise awareness of the barbaric Southern practice of lynching Black men as a method of enforcing Jim Crow segregation. Here is the opening of the poem:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Meeropol’s success as an ally was confirmed by his next step, which was to set his poem to music. He then offered the song to jazz singer Billie Holiday, whose 1939 recording was the best selling recording of her career. As a Black singer making records for a Black audience, Holiday’s success with “Strange Fruit” certifies Meeropol as a genuine ally.

Beyond acceptance from the relevant community, allyship can be measured in terms of its impact as a political gesture (Fried 2019). Impact depends on whether it successfully communicates its critique to the dominant culture. Political impact is difficult to measure. Given that Time magazine declared it “Song of the Century” in 1999, “Strange Fruit” passes this test (Lynskey 2011).

Political impact is difficult to determine for an artist such as Homer. His cultural position and other work are closely identified with the dominant culture, and his works of allyship were not popular successes. Despite these obstacles, Homer created a body of work involving cultural appropriation that meets Addison Gayle’s criteria for conveying Black culture in art. According to Gayle, content appropriation should “recognize and insist upon the validity of an African American culture that encompasses not only the retentions of the African cultures from which the enslaved population was drawn, but also the unique culture that the enslaved developed out of the conditions and imperatives of their lives in the U.S.” (summary of Gayle in Shockley 2011, p. 4; see also Gayle 1994). Homer’s Dressing for the Carnival satisfies these demands to a high degree.

Locke’s early praise for The Gulf Stream is significant because it was largely dismissed as ugly and unpleasant during Homer’s lifetime. (See figure 6.8.) Until a museum bought it, it was for sale for more than five years without a buyer. As with many complex artworks, The Gulf Stream has been interpreted in several ways. The only one of these that will be discussed here is the interpretation that takes the painting at face value: this is a representation of a Black man at the dawn of the 20th century. Given Homer’s audience and the decision to create an oil painting, the image is (presumably) intended to be seen by a White, well-off audience. However, there is no sense that the man on the boat is speaking to the viewer in any way — there is no dimension of voice appropriation. Nonetheless, Homer has created a complex symbol about Black and White America.

Homer created The Gulf Stream after a time sketching in the Bahamas, but the title leaves the location of the scene open to interpretation. This small fishing boat could have sailed from Cuba, or Florida, or even North Carolina. The boat has been battered by a storm, and the man is threatened by sharks and by the approach of another storm. He has no mast or sail, so no power. He cannot steer – the rudder is gone. He is adrift and at the mercy of others. There is the potential for rescue — a ship is on the horizon at left. But will they see him even if he spots them and signals? Stalks of sugar cane are on the deck beside him, reminding the viewer that the sugar industry of the Americas was a major reason for the slave trade. So, this image does not symbolize, as some would have it, “man against nature.” As Albert Boime says, “Homer’s besieged fisherman is an allegory of black people’s victimization at the end of the nineteenth century” (Boime 1990, p. 36). The man’s posture is ambiguous. He might be resigned. He might be defiant. Either way, the painting “conveys the paradoxical destiny of ‘freed’ black people in modern society” (Boime 1990, p. 46.) The Gulf Stream vividly demonstrates that cultural appropriation is compatible with being an artistic ally of non-dominant groups.

6.5. Employing Dual Appropriations

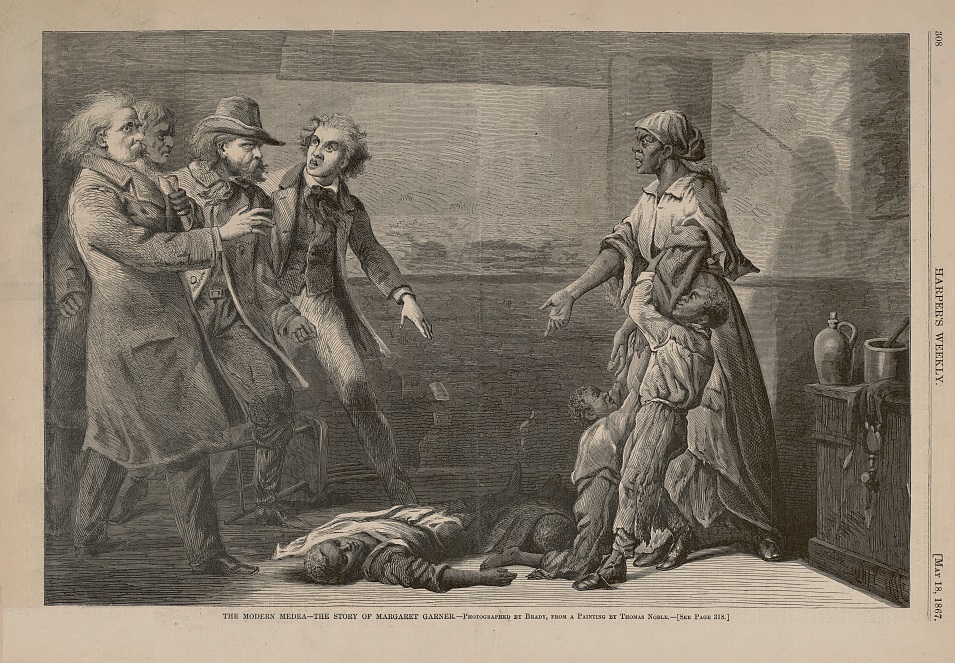

The examples of Twain and Harte suggest that allyship can easily go wrong, while the example of Homer shows that it can succeed. Despite Locke’s high praise, it would be wrong to think that Homer was singular in achieving allyship in visual art in the second half of the 19th century. One of Homer’s contemporaries used dual appropriation to the same end. In dual appropriation, an artist appropriates from two different cultures at the same time. Consequently, this approach can put three cultures into dialogue. Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s painting Margaret Garner is an example of using dual appropriation to achieve a complex cultural interplay. (See figure 6.9.) In showing a tragic moment in the life of Garner, Noble engages in content appropriation. And it is cultural appropriation, because a White man is illustrating a moment in the life of a Black woman. The basic design of the image is appropriated, as well — from yet another culture. There is a question of whether her hand gesture is voice appropriation, but that can be set aside because the overall point of the image is the content appropriation that places it in the genre of “true crime” documentation. As explained above in relation to the content appropriation of exoticism, presentation of Garner’s perspective is not the actual goal. Noble is illustrating her story in order to make his own statement about the fragile, undecided status of recently emancipated slaves.

Noble’s painting became widely known because a reproduction was published in Harper’s Weekly, the same weekly magazine that made Winslow Homer a household name. Harper’s Weekly renamed the image The Modern Medea. Painted immediately following the Civil War, the picture illustrates the story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman who fled north to Ohio in 1856. Under the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1850, free states were required to cooperate in the capture and return of enslaved people. When Garner was located near Cincinnati, she decided to kill her children with a butcher knife rather than let them be taken and returned to enslavement. She had killed one child and wounded two others when slave hunters broke into the house and seized her. Her tragic story was widely publicized in Northern newspapers when it led to a court case that debated whether the state of Ohio could charge her with murder, which would require a court ruling that Garner was a free woman. Noble’s picture is a content appropriation of the most dramatic moment of her story, illustrating the arrival of the posse and their disruption of her desperate act.

By reminding the public of Garner’s story a decade after it took place, Noble is engaging in allyship in the same way that Homer did with A Visit from the Old Mistress and Dressing for the Carnival. Both artists are portraying real people and inviting viewers to interpret their pictures in relation to American politics following the ending of the Civil War. Noble’s picture was produced a few years earlier than the pair by Homer. Noble painted his at the beginning of Reconstruction, while Homer painted his two as it came to an end. In relation to current events, “the political and cultural context for Noble’s rendering was fundamentally different from surrounding Margaret Garner’s actions in Cincinnati. In a nation partway through ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment, the conflict over slavery and abolition had given way to an equally fierce debate over equality, black autonomy, and the terms of Reconstruction” (Reinhardt 2010, p. 262). Although slavery had been outlawed, the former Confederate states were uncooperative, passing laws that would establish legal segregation. In response to this problem and other issues, The Reconstruction Act of 1867 required the rebel states to guarantee voting rights for Black men as a condition for rejoining the United States with voting rights for White men. Garner’s image was painted and shown during the debate surrounding adoption and implementation of that law.

Thus, in 1867 the dominant culture would have understood Noble’s image as an endorsement of the Reconstruction Act. It was created as a reminder that slavery was a brutal institution and so terrible that murder was plausibly seen as a lesser evil than having one’s children grow up enslaved. Without exactly excusing Garner, Noble guided interpretation of her action by building the image around a second cultural appropriation. Many viewers would have immediately recognized the motif or design appropriation guiding Noble’s placement and poses for the adult figures in the picture. Their placement and poses are a cultural appropriation from a famous painting, The Oath of the Horatii. (See figure 6.10.) Like Noble’s own painting, this French painting of 1784 was popularized in engraved reproductions.

The Oath of the Horatii concentrates on four figures. On the left, three brothers pledge to defend Rome to their father, the figure on the right. Noble’s image employs a copycat grouping. Other than her arm placement and the direction of her gaze, Garner has the body stance of the father. The slave hunters have the body stances of the brothers. Since the similarity is not coincidental, Garner’s visual allusion to The Oath must be a prompt to think about the connection between the two stories.

The Oath was understood in its time — and ever since — as a reminder that there is an ongoing struggle to secure the rights and privileges of liberty. Although it is a history painting about ancient Rome, David’s painting was understood to support the French Revolution, a political event of his own time. By using motif appropriation to make a connection between Garner and The Oath, Noble is asking the audience to interpret this horrifying moment in Garner’s story as another act in the historical defense of liberty. The 14th Amendment must be ratified and the rights of the formerly enslaved secured, Noble is suggesting, or the United States will cause further tragedies of this kind.

There is an additional bit of cultural appropriation here, from yet another culture. Noble tiled his image Margaret Garner, but someone at Harper’s Weekly added the words The Modern Medea (Boime 1990, pp. 146-47). What does the expanded title mean? Who was Medea? In ancient Greek stories, Medea was the lover of Jason, but he betrayed her to marry someone else. In rage, Medea murdered their children with a knife. In the version of the story that has come down to us in a play by Euripides, the gods actually assist Medea, implying that they forgave her wrongdoing because she did it in response to a wrong done to her. Here, again, cultural appropriation implies that it would be wrong to simply condemn Garner. We cannot judge her unless we understand what drove her to do such a terrible thing.

By gesturing back to the time just before the Civil War and emancipation, Noble engages in content appropriation. He then deepens its meaning with another cultural appropriation, a motif appropriation from Jacques-Louis David’s well-known painting. Sharing Noble’s work with a larger audience, Harper’s Weekly adds further content appropriation by giving the image a new title. With or without the Medea reference, Noble’s painting makes him an ally of the millions of Black Americans who awaited their fate at the hands of a country undecided about its commitment to freedom and equality for Black people.

6.6. Appropriation and White Ethnic Americans

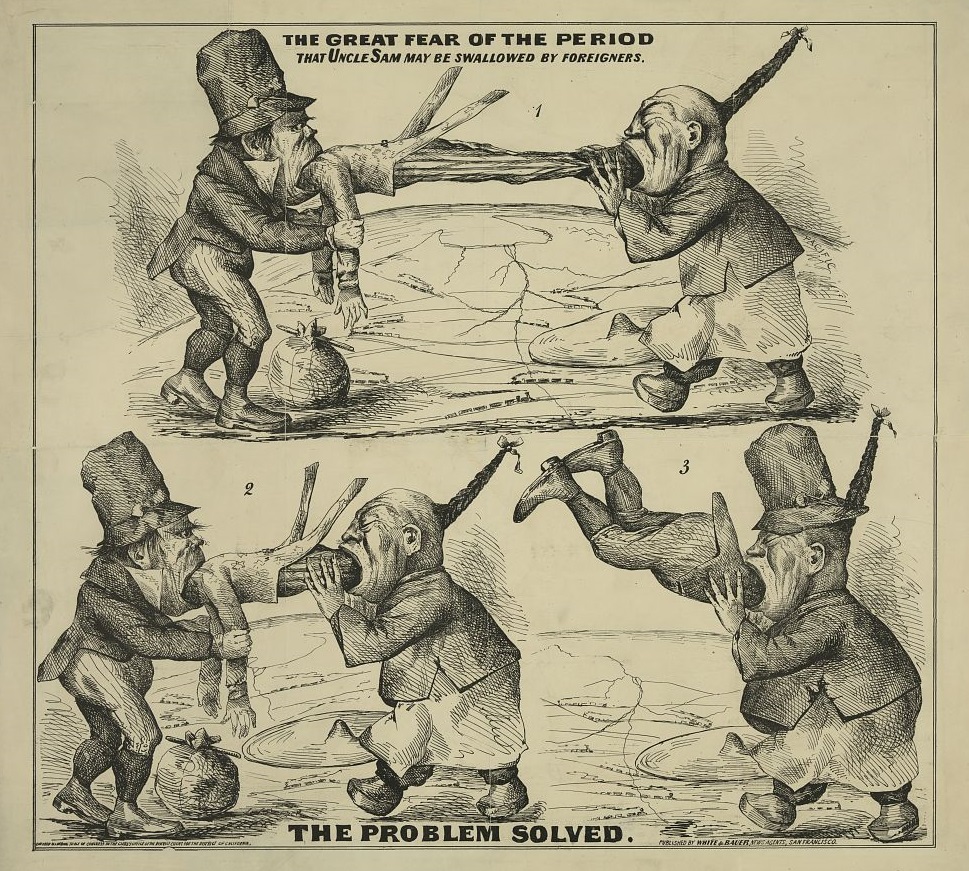

As explained in Chapter 4, Section 4.7, and above in Section 6.3, Irish immigrants were not immediately accepted as members of the dominant White culture. A wave of Irish immigrants began to pour into the United States after famine struck Ireland in the 1840s. Many of them found work as unskilled physical laborers, such as leveling ground for new roads and digging the Erie Canal. After the United States government decided to fund a transcontinental railroad linking California and the East in 1862, Irish immigrants supplied the bulk of the labor force of the line heading west across the central plains. At the same time, a second rail line, the Central Pacific, headed east into the mountains to meet them. The Central Pacific actively recruited its labor force in China, bringing in a fresh wave of young men to supplement the generation that had arrived to support the gold rush. Although the country wanted cheap manual labor, many people saw both immigrant groups as threats to the dominant culture. One popular political cartoon showed the two groups headed toward each other across the continent, gobbling up Uncle Sam. (See figure 6.11.) The railroads they were building can be seen in the background. Notice that this is a variation of Bret Harte’s poem about the cheating gamblers: Irish laborers compete with Chinese laborers.

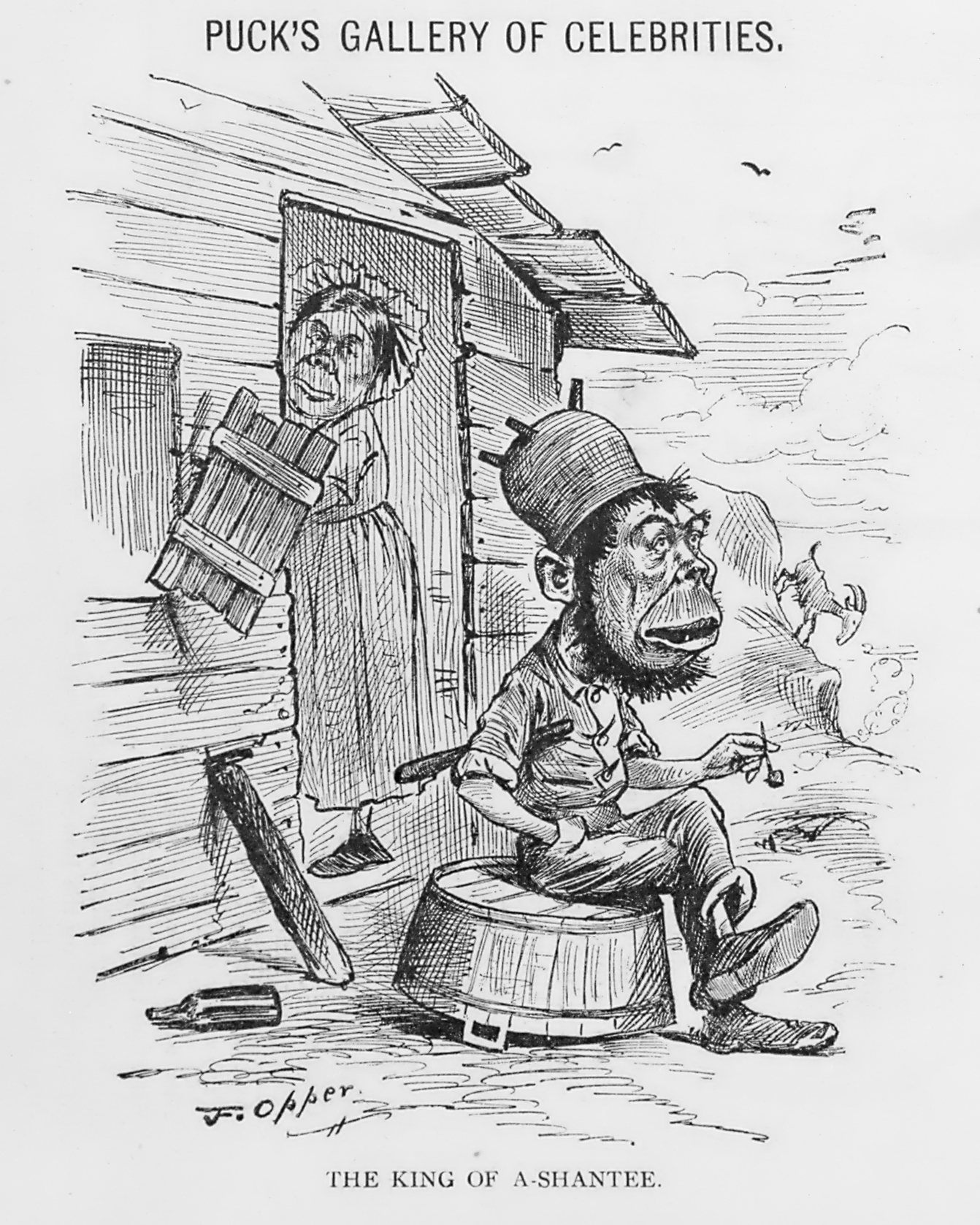

This cartoon references “foreigners” and it does not directly state that the men are Irish and Chinese. Instead, it engages in content appropriation that most Americans would immediately recognize as stereotypes for those two groups. In the case of the figure on the right, the long hair braid or queue was a standard stereotype that signified Chinese ethnicity. However, the Irish laborer also conforms to a stereotype that appears in countless drawings in the 19th century. Just as the Chinese man is stereotyped by the bamboo cone hat on the ground beside him, the Irish man is assigned a distinctive style of cap. The Irishman’s face is notably monkey-like. This stereotype was a content appropriation in which American artists copied from English drawings and cartoons that pictured the Irish as a backward race. (See figure 6.12.) Historically, the English takeover of Ireland originated the model of settler-colonization that the English later used in North America. In both cases, the English stressed the racial inferiority of the ancestral landholders and replaced them with settlers who would engage in agricultural development.

Through content appropriation, the English stereotype of monkey-faced Irish people was widely adopted in the United States. (See figure 6.13. See also Chapter 2, Figure 2.13.) An American humor magazine commented that this comparison was not an insult to the Irish, but to monkeys (Life 1893, p. 303).

The point of this dehumanizing content appropriation was to affirm that the Irish were racially, and not merely ethnically, different. One reason was that the country’s English heritage included centuries of racist mistreatment of the Irish. Another factor was that the Protestant culture of the United States was hostile to the immigration of Roman Catholics. The complaints and warnings that were raised about Irish immigrants became a blueprint that is still used in the United States — although now against other groups.

The standardization of anti-Irish racism is clearly illustrated by a “humor” piece by one of the most popular authors of the 19th century, Louisa May Alcott. She is best known for the novel Little Women (1868-69). Because that novel is so progressive on the topic of women, it may surprise its fans to learn that Alcott supported the “nativist” anti-Irish movement, and that she did so using racial stereotyping. In the essay “The Servant-Girl Problem” (1874), Alcott uncritically adopted prevailing stereotypes and advised her readers against hiring Irish women for housekeeping jobs. If they followed her advice, Alcott promised, her readers could find good help among native-born “American women.”

Excerpt from “The Servant-Girl Problem: How Louisa M. Alcott Solves It

… Last spring, it became my turn to keep house for a very mixed family of old and young, with very different tastes, tempers and pursuits. For several years Irish incapables have reigned in our kitchen, and general discomfort has pervaded the house. The girl then serving had been with us a year, and was an unusually intelligent person, but the faults of her race seemed to be unconquerable, and the winter had been a most trying one all around. My first edict was, “Biddy must go.” “You won’t get anyone else, mum, so early in the season,” said Biddy, with much satisfaction at my approaching downfall. “Then I’ll do the work myself, so you can pack up,” was my undaunted reply. Biddy departed, sure of an early recall, and for a month I did do the work myself, looking about meantime for help. “No Irish need apply,” was my answer to the half-dozen girls who, spite of Biddy’s prophecy, did come to take the place. …

I found a delicate little woman of thirty, perhaps, neat, modest, cheerful and ladylike. She made no promises, but said, “I’ll come and try;” so I engaged her at three dollars a week, to take charge of the kitchen department. She came, and with her coming peace fell upon our perturbed family … alas, my little S. did go, because she only came for the summer and preferred the city in winter.

Cheered by my first success, I tried again, and found no lack of excellent American women longing for a home and eager to accept the rights, not privileges, which I offered them. … . These women long for homes, are well fitted for these cares, love children, are glad to help busy mothers and lighten domestic burdens, if, with their small wages, they receive respect, sympathy and the kindness that is genuine, not patronizing or forced. Let them feel that they confer a favor in living with you, that you are equals, and that the fact of a few dollars a week does not build up a wall between two women who need each other.

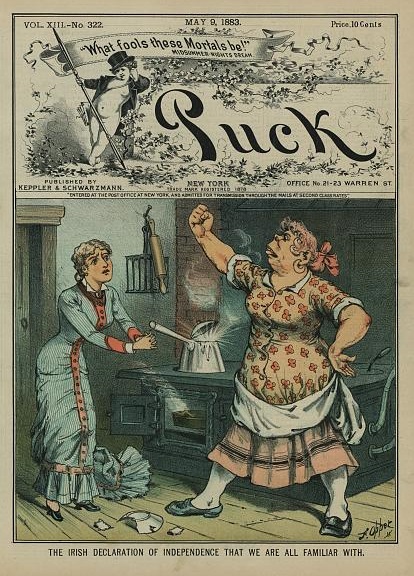

Alcott says that the Irish are a “race” of “incapables.” She does not say why. She is counting on her readers to be aware of the stereotype that the Irish are short-tempered, violent drunks. An image published in the humor magazine Puck can serve as an illustration of Alcott’s unspecified experiences with Biddy. (See figure 6.14.) Alcott says that the desirable qualities of an employee cannot be found among the Irish. Her ideal employee is “neat, modest, cheerful and ladylike.” Presumably, Biddy was the opposite of each of those qualifications. (Incidentally, “Biddy” was probably not her name. It was a generic nickname applied to all Irish women by members of the dominant culture, and therefore functioned like a racial slur.)

Alcott’s further message is that the secret to good help is a social relationship in which the employee will “receive respect, sympathy and the kindness that is genuine, not patronizing or forced. Let them feel that they confer a favor in living with you, that you are equals.” Alcott is saying that “American” women have a “right” to be treated as equals. By implication, this was impossible with her Irish cook and, by extension, other Irish women. From Alcott’s perspective, the Irish are racially inferior, and cannot and should not be treated as equals. The social relationship that is needed in the household cannot be extended to Irish help. Therefore, “No Irish need apply.” Other than its authorship by Alcott, this anti-Irish essay is unremarkable. It is simply one of many 19th-century content appropriations portraying the Irish as racially unfit for assimilation into White America.

These standardized, negative stereotypes of Irish immigrants originated in England Their appropriation by Americans shows that 19th-century thinking about race does not match its current social construction. However, the idea that the Irish were a distinct racial group and “not quite” White gradually faded, giving way to the idea that the Irish are fully White and merely ethnically distinct (Heinz 2013). Americans have not been consistent about who is, and who is not, welcome in the dominant culture.

6.7. Copycat Appropriation: Sherrie Levine

Until this point, cultural appropriation has almost always been framed in terms of the dominant culture’s appropriations from non-dominant cultures that have a distinct ethnic or ancestral identity. However, subcultures can also form and carry forward without reference to shared ancestry. We speak of the culture of medicine, the culture of science, and the culture of academia. Medical doctors, research scientists, and university professors have traditionally been members of the country’s dominant culture. Nonetheless, each of those fields has established values and practices that are handed down between generations and which conflict, in many ways, with the values and practices of the dominant culture. This is particularly the case given the strong strain of anti-intellectualism in the dominant culture (Hofstadter 1963). However, because these subcultures have high status in American society, they are not oppressed groups.

Creative artists, writers, and musicians can also be viewed as loosely organized into distinct subcultures. However, at least since the importation of “the Bohemian” artistic lifestyle from France in the mid-1800s, these groups have generally been regarded as out of step with the dominant culture. (See figure 6.15.) As a subculture, the artistic underclass has been seen as rebellious, subversive, and anti-establishment. As such, they are socially constructed as one or more distinct non-dominant or subordinate cultures. This distinctive cultural zone is often called “the artworld” (Danto 1964).

In many contexts, women function as members of a non-dominant culture. This is true even in the case of women who otherwise belong to the dominant culture. To be clear, women are here understood in relation to gender. As a social construct, gender operates much like race. Collectively, society distinguishes between social roles that are permitted and prohibited to members of these groups, and negative consequences — up to and including violence — are used to enforce conformity. This pattern of discriminatory treatment is then justified by appeal to shared “natural” or biological characteristics that are not actually aligned with inherent tendencies and behavioral traits. As with race, gender expectations are developed, codified, and circulated in numerous cultural products, and in both fine art and popular art.

For example, the United States has operated with the social norm that adults will marry and establish their own self-supporting homes. From a global and historical perspective, this expectation is culturally unusual. It was a relatively unique pattern of family life that developed in the Protestant culture of northwest Europe. Protestant immigrants from that region established it as an element of the dominant culture of the colonies that became the United States (Smith 1993). On this model of family life, the man is “head” of an independent “nuclear” family, and he is the “breadwinner.” The wife is expected to bear children and to devote herself to the role of “homemaker.” The husband is the decision-maker and the wife is expected to obey those decisions.

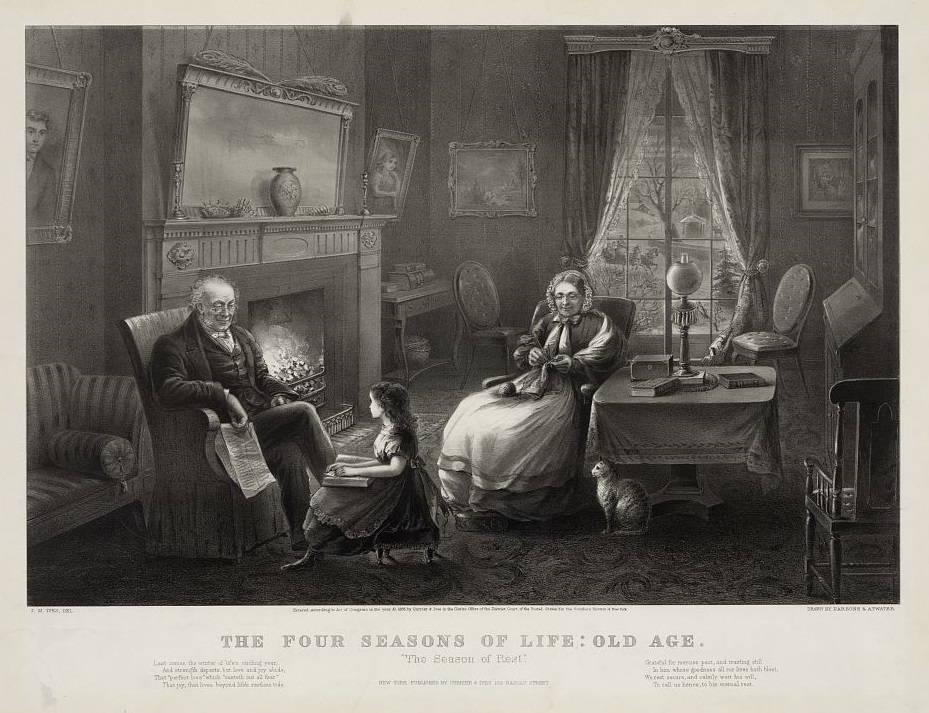

As in many examples previously discussed, these cultural norms are frequently communicated through the repetition of stereotypes that convey subtle messages. Consider the domestic scene of “Old Age,” the fourth in the Seasons of Life set of prints mass-produced in the 19th century. (See figure 6.16.) This scene is an idealization. At the time the picture was created, the United States was experiencing high rates of widowhood and abandonment of wives. In the South, the rate of widowhood was about 1 in 3 for White women who had married (Hacker, Hilde, Jones 2010). In the image, a sled is visible through the window, so the setting is not the South. An elderly couple sits by the fire. The husband holds a newspaper, showing his ongoing connection with the world outside the house even after he has, presumably, retired. His wife is knitting. A young girl — a granddaughter, no doubt — is positioned so as to literally look up to the male figure. His attention and approval are prioritized. He is the head of the house, while his wife has no rest from chores to maintain the household.

One of the social roles that has long been denied to women is that of creative artist. Once the dominant culture’s expectation that women remain at home met up with the 19th-century idea of the artist as a footloose-and-fancy-free Bohemian, the category of “woman artist” counted few examples. Linda Nochlin, an art historian, documented the social barriers to women’s participation in the modern artworld in the essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (Nochlin 1971). She answered the question in her title by observing that there cannot be “great” women artists — ones with the status of Leonardo da Vinci, Vincent Van Gogh, and Pablo Picasso — in a culture that won’t allow women to devote their lives to full-time pursuit of art.

Things improved during the 20th century in one way. The number of women artists is now roughly equal to the number of men (National Endowment for the Arts 2019). However, their earnings and employment status are not at the same level. Within the artworld, women face more barriers than men. In the 1980s, a group of American women artists working collectively as the Guerilla Girls made it their mission to highlight these barriers for women artists. For example, they created posters that shamed The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They pointed out that the museum ignored living women artists. When purchasing art by recent and living artists, 95% of the purchases were of male artists (Freeland 84-85). Things have not improved since then. Museums and collectors simply do not purchase art by women at the same rate that they purchase art by men, and when they do, they pay far less. A recent study found that when we exclude the cost of the most expensive art by male artists, such as paintings by da Vinci, art by living women artists sells for about 60% of what men receive (Elsesser 2022).

With this cultural background in mind, it is not surprising that women artists have used art appropriation to criticize the artworld itself. One of the most interesting examples is the photography of Sherrie Levine, who uses content appropriation to call attention to the cultural barriers that hold back women artists. Levine did not invent the technique she uses. However, her version of it is so blatant and obvious that it serves as a model for thinking about appropriation as a powerful tool for artists with non-dominant identities.

The technique used by Levine is the mirror opposite of exoticism. It involves the appropriation of familiar content from the dominant culture by someone who is a member of a non-dominant group. In this way, it reverses the power dynamic that occurs in most cultural appropriation. This appropriation from the dominant culture is carried out with the full expectation that the audience will know that it is a reverse form of cultural appropriation. As such, it is a tactic for challenging norms and values endorsed by the dominant culture.

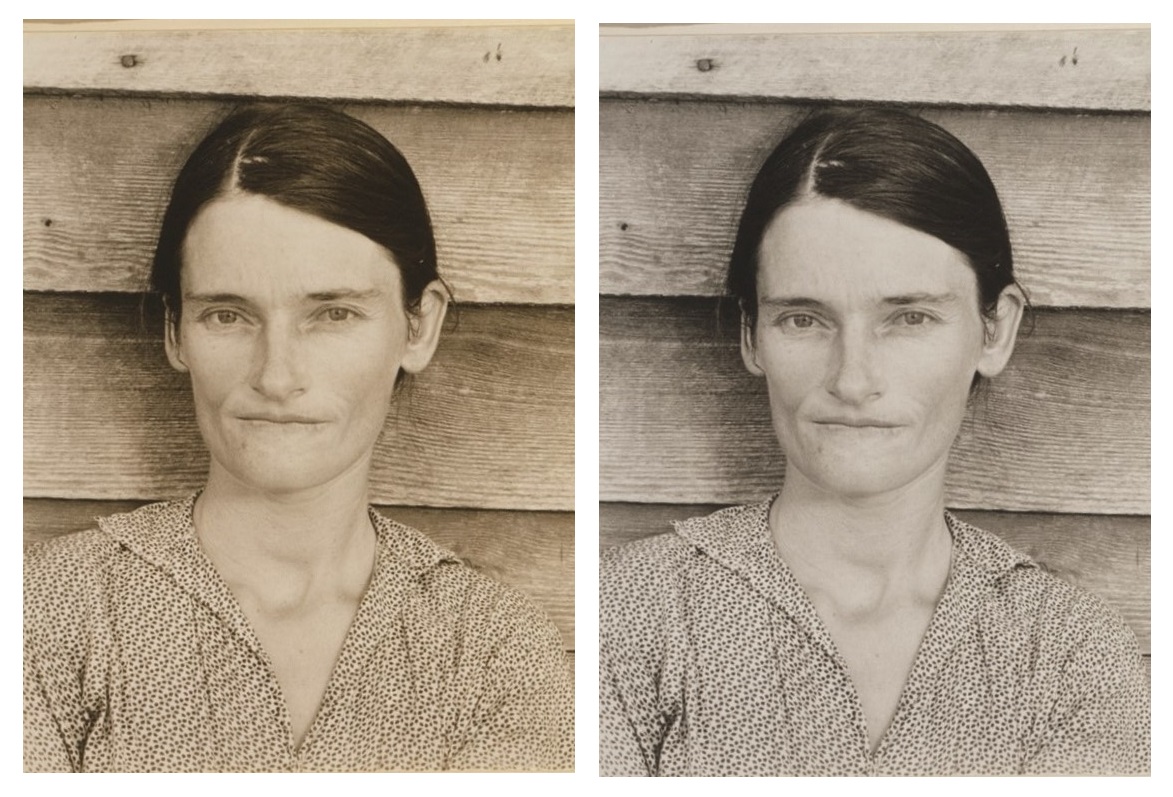

In Levine’s case, the appropriation is direct and minimally transformative. She used photography to stage content appropriation from a male artist in a way that challenges viewers to think about her position as a woman in a male-dominated artworld. The best-known examples of her work are the photos exhibited in 1981 in the series After Walker Evans (see figure 6.17.) Evans was hired by the Farm Security Administration, a department of the U.S. government, in the 1930s. He was one of many artists hired to document ordinary Americans, especially those who were struggling due to the economic troubles of the Great Depression. Because these were works commissioned by the Federal Government, the Library of Congress makes some of them available without copyright restriction under the fair use doctrine. Levine used a book of Evans’ photos and photographed his photos. She then displayed a set of these as her own work. Although they looked almost identical, she was exhibiting her photographs, not his. (Her work is protected by copyright, and therefore a new original digital photograph is shown in the right panel instead of one of hers.)

Levine’s point in making such direct copies of another artist’s work is to call attention to the social construction of art in modern life. That is, it calls attention to the way that social institutions create a category of “artist” along with associated rules about what counts as art and who gets to be an artist — and who does not. In this way, it also calls attention to the social determination that Evans was male and Levine is female.

Faced with such a direct and blatant content appropriation, the viewer is also invited to confront the issue of why U.S. law treats the two photographs differently. Why is one his, and the other hers? This question leads to the bigger issue. What does it mean to put an artist’s name on a work? What are the social implications? One of the implications is that we live in a society where a man’s name is worth more than a woman’s name. Against the claim that Evans was doing something original in making art, but Levine was not, it is important to notice that the Evans photograph is already an act of cultural appropriation, bordering on exoticism, in showing struggling Southern farmers. To a certain extent, Levine is simply doing what Evans did. (Notice the parallel here to Bret Harte’s juxtaposition of Bill Nye and Ah Sin.) The point of Levine’s appropriation is that there is a difference, but it is not visual. It is a difference rooted in, and addressing, the overlapping norms of gender, money, and social recognition in Western culture.

6.8. Music Performance: Nina Simone and Jimi Hendrix

Sherrie Levine was not the first artist to launch a protest by appropriating content from the dominant culture. The technique has been used countless times by others, and it is often used in cases that the dominant culture classifies as mere entertainment. The primary value of focusing on Levine is that the After Walker Evans series is minimally transformative. The important differences are not visible. They arise from the invisible social constructions that distinguish art from the rest of life. In this way, Levine’s work showcases her “outsider” status: she relies on audience awareness of her non-dominant cultural position. Audience awareness of her status is what allows her to use cultural appropriation to challenge the dominant culture.

With this in mind, this section examines a pair of similar examples, but ones involving music rather than visual copying. In the case of music, content can be strictly musical content, that is, the music apart from any words. With many well-known songs, listeners can recognize what it is in less than one second, even before any words are sung. If someone of one culture performs music created in another, it is automatically cultural appropriation of content. At the very least, it involves appropriation of the musical content. If there are words but those words do not signal that the song comes from a different culture, the appropriation can be content appropriation without being voice appropriation. The American song “Happy Birthday to You” is sung by people in many distinct cultures, but these appropriations are not likely to be categorized as voice appropriation. People are using content to give voice to their own celebration.

In cases where there are no obvious signs of voice appropriation, a song appropriation by a performer who belongs to a non-dominant group can function very much like Levine’s After Walker Evans series. It can make a political statement simply by being re-authored from a different cultural position. We can find a number of examples of this during the 1960s, when Black Americans used both political and media tools to campaign for the ending of segregation and exclusion. Performances by Nina Simone and Jimi Hendrix provide two clear examples of this kind of musical content appropriation.

Nina Simone was the stage name of Eunice Wayman, a Black pianist and singer who mixed together jazz, classical, blues, and mainstream popular music. As Daphne Brooks explains, “she forged her own form of musical integration and performative agitation … and [challenged] cultural expectations of where black women can and should articulate their voices” (Brooks 2011, p. 179). For example, during a 1964 concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall that was released as the recording In Concert, Simone performed the song “Pirate Jenny.” The song originated in a German stage musical of 1928, The Threepenny Opera, with music by Kurt Weill and lyrics by Bertolt Brecht. Their musical was itself a cultural appropriation of an English musical, The Beggar’s Opera, and therefore the story is set in London. However, German audiences certainly understood The Threepenny Opera as a portrait and celebration the underclass of Berlin that was meant to challenge the expectations and hypocrisy of the middle and upper classes of German society. “Pirate Jenny” is a song of revenge. Jenny is an abused, underpaid maid. She sings a fantasy of revenge in which she reveals that she secretly commands a pirate ship that will soon arrive, and the pirates will slaughter everyone she dislikes in the hotel.

It might be thought that an American performance of this song is both voice appropriation and content appropriation. After all, Simone is representing someone else’s voice. However, that voice is a fictional character, Jenny, and there is no voice appropriation as normally understood. There is nothing in the song that ties it to its originating place and time, Germany of the 1920s. The key cultural references — a hotel maid and pirates — are not alien to Simone’s own social background and cultural heritage. There were, after all, female pirates. (See figure 6.18.) Simone was born and raised in North Carolina, and piracy was part of the history of North Carolina, producing one of history’s most famous pirates, Blackbeard. Many slaves and escaped slaves were among known pirates, and there is even a legendary woman pirate from Haiti, Jacquotte Delahaye, reputedly born of a French father and Black Haitian mother. However, aside from all that, the voice represented in a performance of “Pirate Jenny” is simply that of a maid engaged in daydreaming, and anyone who knows a small amount of history might daydream of pirates. There is nothing in the song that is foreign to anything in Simone’s life, and so there is no basis for treating her performance as voice appropriation.

Like Levine’s photographs, the impact of the appropriation depends on audience understanding of who appropriates from whom. In Simone’s case, many in her Carnegie Hall audience may have seen The Threepenny Opera a few years before during its lengthy off-Broadway run in New York. In this way, her performance of “Pirate Jenny” offered a richer experience for those who understood that something created by someone in a more privileged position was being used as political and social protest by someone in a less privileged position. However, for listeners who do not know that “Pirate Jenny” was from a famous play co-written by a German poet and a German musician, one could listen to a recording of the performance and think that Simone composed and performed a song that she wrote herself. It would still have a powerful political impact.

Other than to sing that the hotel is in a “crummy Southern town,” Simone sticks to the lyrics as translated into English for American stage performances. However, coming from Simone, Jenny is assigned a racialized identity. Simone is presenting the character of a Black maid who is fed up with segregation and her mistreatment. The pirates arrive and round up everyone in the hotel, and she gets her revenge:

And they’re chainin’ up people

And they’re bringin’ them to me

Askin’ me “Kill them now, or later?”

I’ll say, “Right now, right now!”

Then they pile up the bodies

And I’ll say

“That’ll learn ya!”

In The Threepenny Opera, the song is about class conflict. Sung by Simone, class conflict is still there, but now it is clearly connected to both feminism and racial conflict. Her performance announces that being a Black woman in the United States places one in a non-dominant group within a non-dominant group. One music critic describes the performance as “ astonishing … It is a theatrical piece that she sings as if she means every word, her vocal dripping with venomous relish as it delivers its saga of murderous revenge: listening to it feels like being pinned to a wall” (Petridis 2023). Fifty years before the founding of the Black Lives Matter movement, Simone used cultural appropriation to highlight multiple issues that motivated that movement. She was also suggesting that rage is a justified response to American racism.

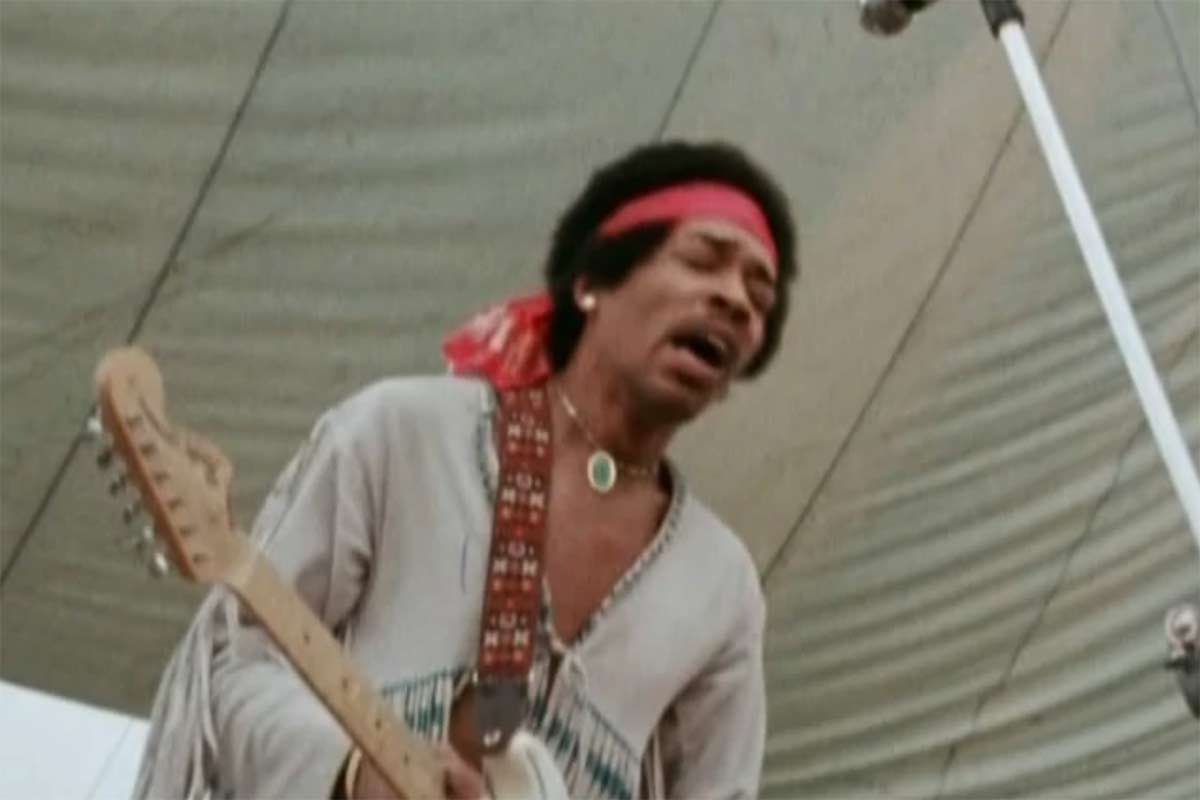

In a more famous example of musical content appropriation, Jimi Hendrix engaged in a complex cultural appropriation as part of his performance at the Woodstock Festival on August 18, 1969. The 3-day festival was one of the first large, multi-day outdoor festivals presenting popular music, and it drew an audience estimated at more than 400,000. The music performances were filmed, leading to a documentary film, Woodstock (1970). The film won an Academy Award (“Oscar”) and has been seen by many millions of people. The festival itself had been a financial disaster, but the film was one of the most profitable movies of its era.

There is general agreement that Hendrix was one of the festival’s highlights. (See figure 6.19.) He was the last musician to play, and much of the audience had departed, heading home. (The festival ran longer than planned. It had been scheduled to end the night before he played.) Rather than focus on one of his hit songs or originals, the filmmakers showcased his bold act of content appropriation. Playing electric guitar, Hendrix performed a solo instrumental version of the American national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” (See Chapter 4, Section 4.2.) The performance is readily recognizable as the anthem despite Hendrix’s use of distortion, bent notes, and introduction of other music alongside the familiar melody. This additional music introduces references to warfare and the military. At one point he uses the guitar to make sounds that mimic screaming, and at another point he makes it sound like machine gun fire. Just after the point where the lyric says “bombs bursting in air,” he disrupts the musical flow to create the sound of bomb explosions with his guitar.

Toward the end of the performance, Hendrix introduces the opening notes of “Taps,” the military bugle call that signals the end of the day. It is frequently played at military funerals and memorial services in a metaphorical announcement that “Day is done … All is well, safely rest” (to quote the unofficial words associated with the bugle call). Hendrix is clearly calling attention to the military casualties in Vietnam. In the summer of 1969, roughly 250 young American men were dying there each week.

It was clear to everyone who heard it that Hendrix was using the anthem to call attention to the ongoing American involvement in Viet Nam. The military draft was highly unpopular with the age group that attended the Woodstock Festival. The United States had recently expanded the war from Viet Nam to neighboring Cambodia with bombings that violated international law. A few weeks after Woodstock, an estimated 15 million Americans participated in a coordinated national protest in which they skipped work and school to march in public against the war. The war was one of the major political issues of the time, and by playing the militaristic anthem and injecting it with a commentary of sound effects, Hendrix was understood by everyone to be using the national anthem to make a statement against current national policies.

Reflecting on this performance 50 years after it happened, Paul Grimstad remarks, “What Hendrix did with ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock, in August of 1969, was … among other things, an act of protest whose power and convincingness were inseparable from its identity as a fiercely nonconformist act of individual expression” (Grimstad 2021). However, expression takes place in a social context. In the same way that Levine’s After Walker Evans series offers a critical perspective framed by the broader feminist movement, Hendrix and Simone offered a critical perspective framed by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Their performances were not simply individual expression. They were Black protest. Mark Clague, a music professor who specializes in the history of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” stresses this point about Hendrix’s performance: “He’s an African American, mixed-race artist who came from a traditional black rhythm and blues background,” says Clague. “At the time, the civil rights movement was playing out. People had just lived through the race riots of the ’60s and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. … So, you have a sort of reverence and revolution at the same time. His performance is both a protest and a fireworks display” (Hawkins 2019). Seen in this way, Hendrix was staging a very public, popular-culture appropriation from the dominant culture. He was simultaneously restating and questioning the anthem from a non-dominant social position.

The Hendrix performance is an example of dialogism, a communication strategy identified and named by Mikhail Bakhtin. Dialogism occurs when a communication creates a dialogue between distinct points of view by inserting two or more perspectives into the same communication or artwork (Bakhtin 1981). Dialogism is slightly different from the cultural interplay found in Noble’s painting of Margaret Garner. All of the cultural components of Noble’s image are advancing the point that the United States should support Reconstruction and live up to its ideal of liberty for all. In contrast, Bakhtin called attention to dialogism as a communication strategy in which distinct perspectives are presented alongside each other. They are not integrated, but remain at odds with one another. Dialogism is therefore a useful tool for highlighting conflicts between the dominant culture and other perspectives.

As such, dialogic mixing of appropriated content is an especially powerful technique for showcasing the voices of non-dominant groups and marginalized people. Most art, literature, and music created by members of a dominant culture will be monologic. That is, most of it will uncritically support the interests of the dominant culture. This point was raised earlier in this chapter in relation to exoticism (see Section 6.2). Exoticism seems to document a different culture, but it actually showcases the values and prejudices of the dominant culture. However, when dialogism interweaves content of the dominant culture with a second, conflicting “voice,” there is an opportunity to address the dominant culture from a perspective that is normally suppressed. This kind of dialogism is precisely what happened whenever Hendrix performed “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Basically, he staged a critical interrogation of the material appropriated from the dominant culture. Looking at Levine’s After Walker Evans series and Simone’s performance of “Pirate Jenny,” those works can be understood as using dialogism to inject a feminist voice into the artworld. The dialogism of the Hendrix performance is probably more obvious, presenting a clear contrast between the familiar melody and Hendrix’s alterations and additions.

Hendrix himself was not open about his intentions in playing — and playing with — the anthem. A few weeks after Woodstock, he was interviewed by popular television talk-show host Dick Cavett, who asked him about it.

Cavett: “when you mention the national anthem and talk about playing it in any unorthodox way, you immediately get a guaranteed percentage of hate mail from people …”

Hendrix: “That’s not unorthodox. That’s not unorthodox.”

Cavett: “It isn’t unorthodox?”

Hendrix: “No, no, I thought it was beautiful.” (exchange quoted in Moores 2019)

On the other hand, when he played the anthem in Los Angeles earlier in 1969, he introduced it by telling the audience that he was going to perform “a song that we was all brainwashed with” (Clague 2022, p. 215). Clearly, Hendrix meant his performances to be understood as a content appropriation from the dominant culture and a response to dominant norms and values.

6.9. Two Popular Songs from Tin Pan Alley

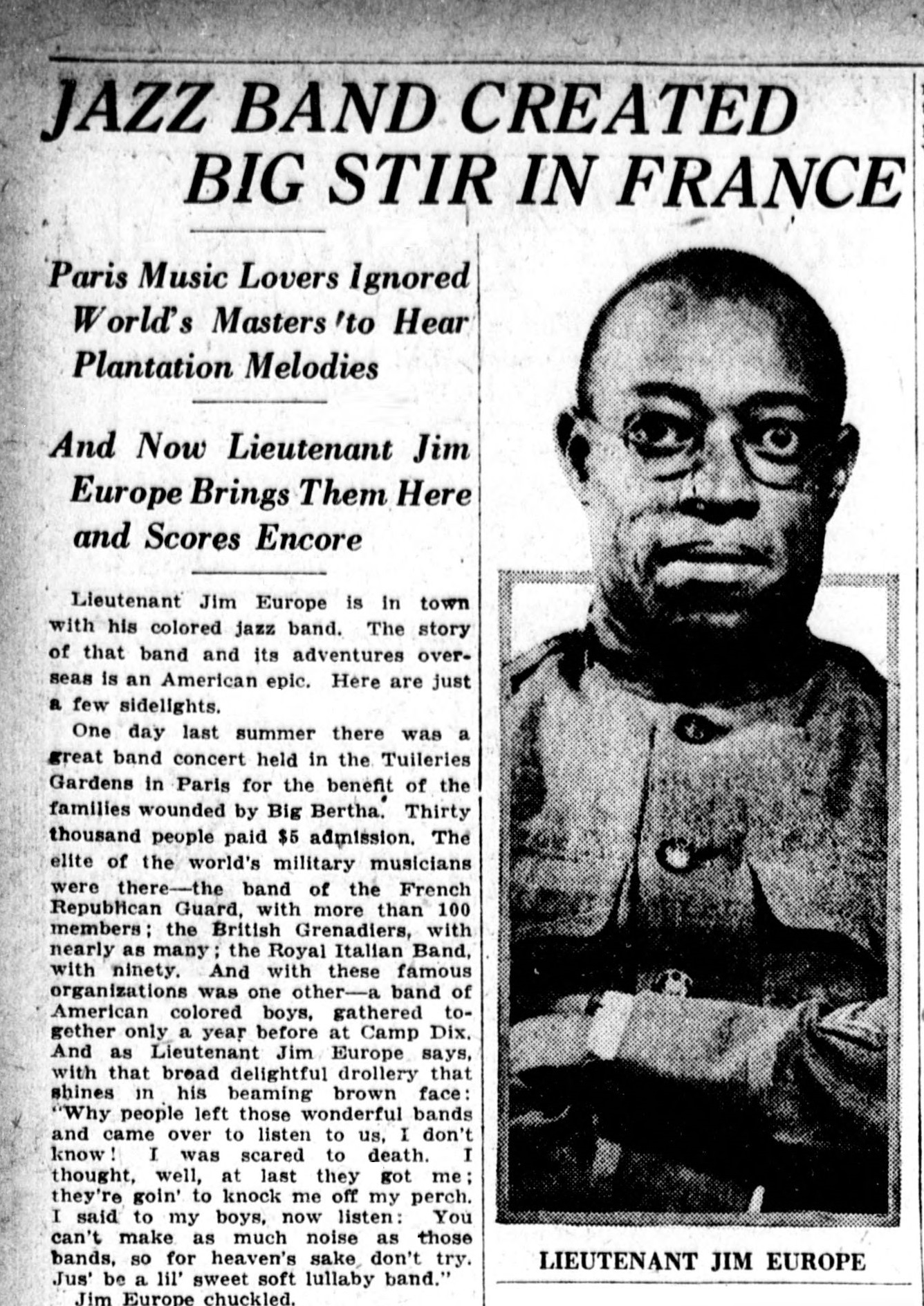

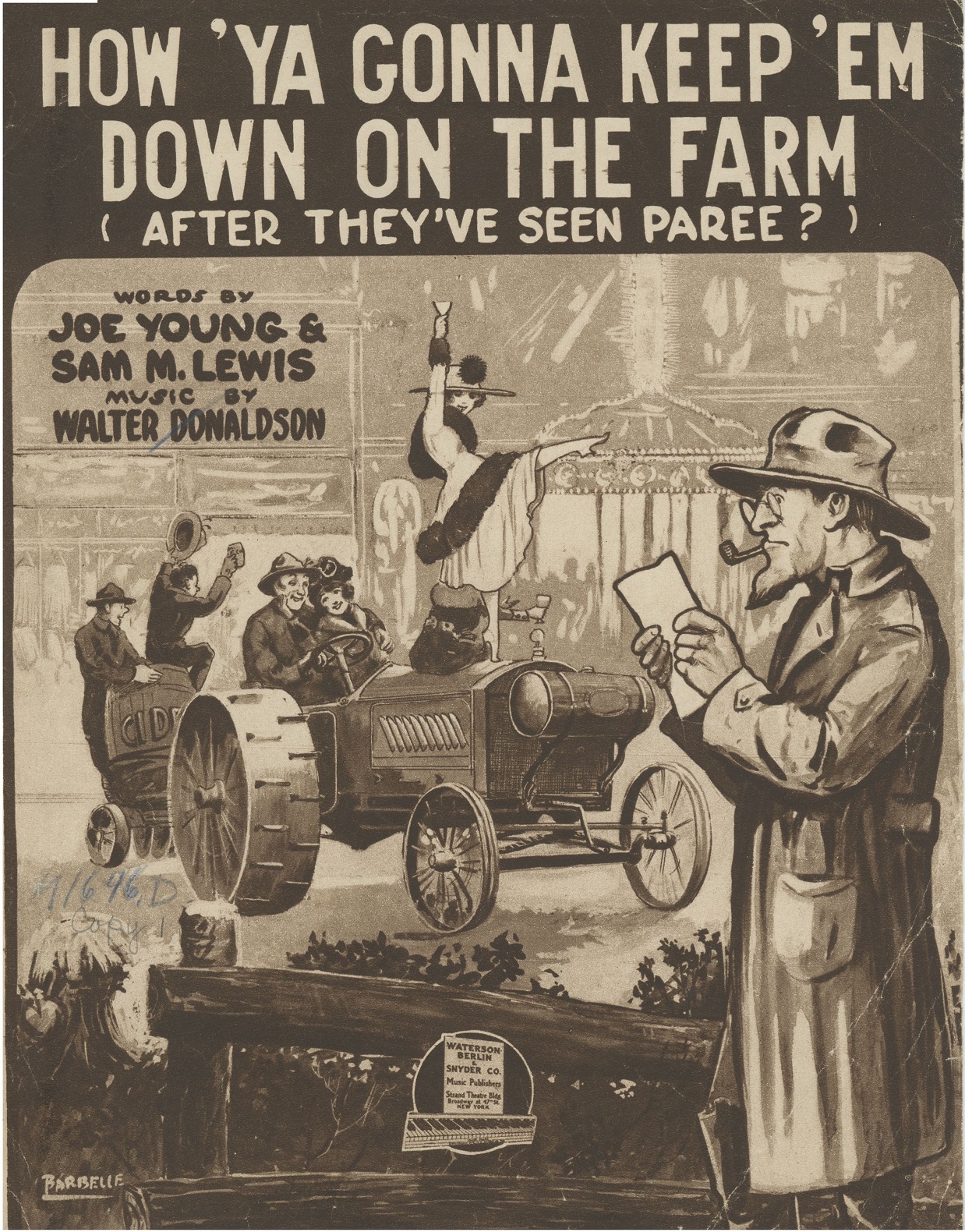

Pushing back in time, we can find other, similar appropriations. “Yes! We Have No Bananas” and “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep ’em Down on the Farm” were two very popular songs from Tin Pan Alley, the knickname for the New York City music publishing industry. Both songs were appropriated — although in rather different ways — by popular performers from non-dominant groups. In each case, the content appropriation created an opportunity for dialogic response in the period immediately after the World War I.

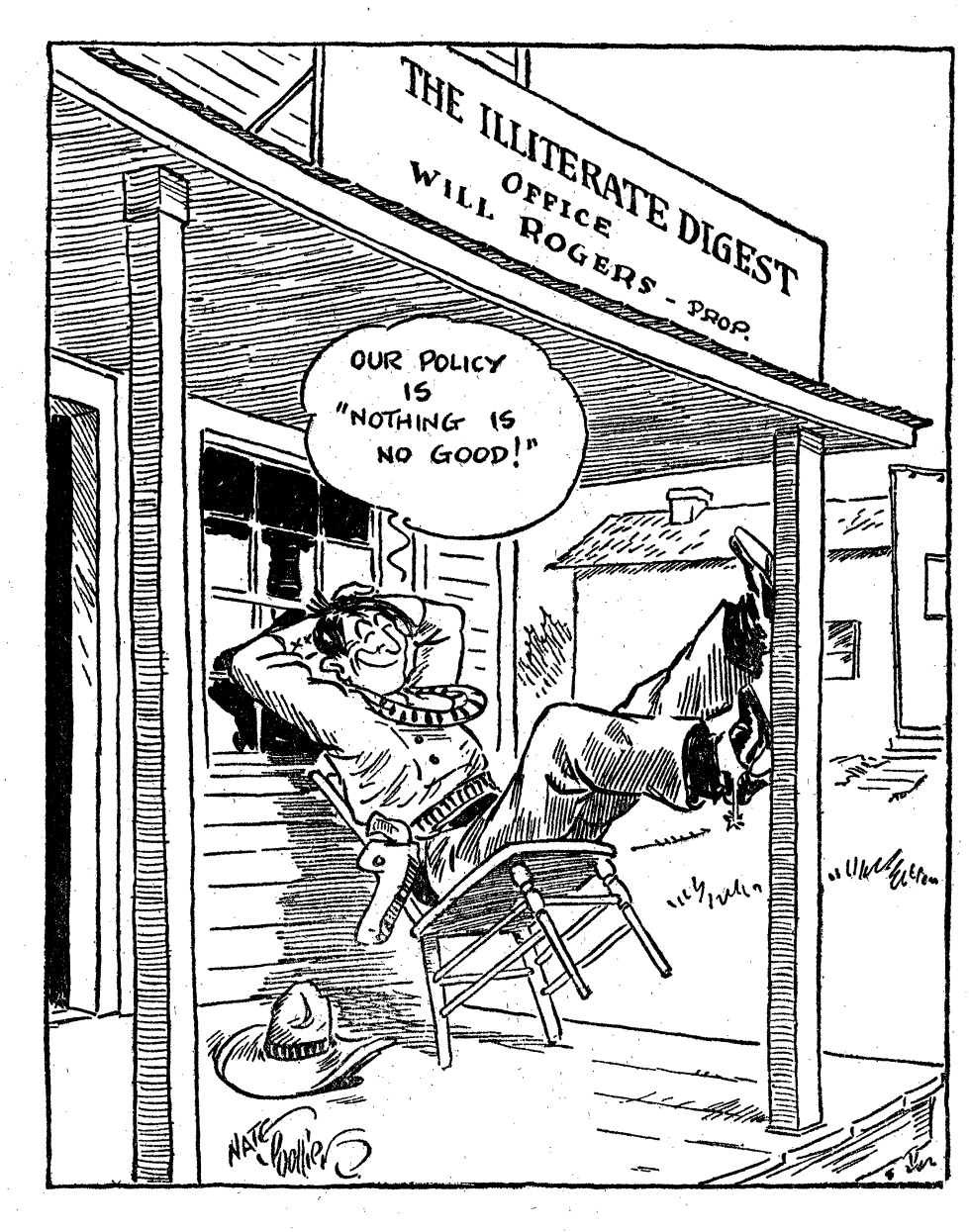

First, we will examine an intervention into the debate about whether to adopt “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem. Aware of the racism of its lyrics and the fact that pro-segregation forces were backing it, comedian Will Rogers argued that an alternative should be selected.

Rogers was one of the most popular entertainers in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. (See figure 6.20.) He was known primarily as a radio comedian and author who specialized in political humor. He appeared in 68 films before his untimely death in 1935 in an airplane crash. Born a member of the Cherokee Nation in what was still officially Indian Territory, Rogers worked as a cowboy and then as a rodeo performer. He specialized in rope tricks, some copied from performances by a Mexican performer, Vicente Oropeza (Ware 2015, p. 55). He then transitioned to being an act in circus shows, touring cowboy exhibitions, and theater shows in which he combined his rope tricks with joke-telling. Although he wore a stereotypical cowboy outfit, he started his career with a stage name that identified his roots: The Cherokee Kid. After Oklahoma became a state, he capitalized on it by rebranding himself as “The Oklahoma Cowboy.” As a result, it is likely that much of his audience did not know of his ethnic identity. At the same time, this background was publicized — for example, stories about it were published when he donated to Cherokee charities — and anyone familiar with the Cherokee Nation could recognize that Rogers’ storytelling style and speech patterns were firmly rooted in that community (Ware 2015, p. 184).

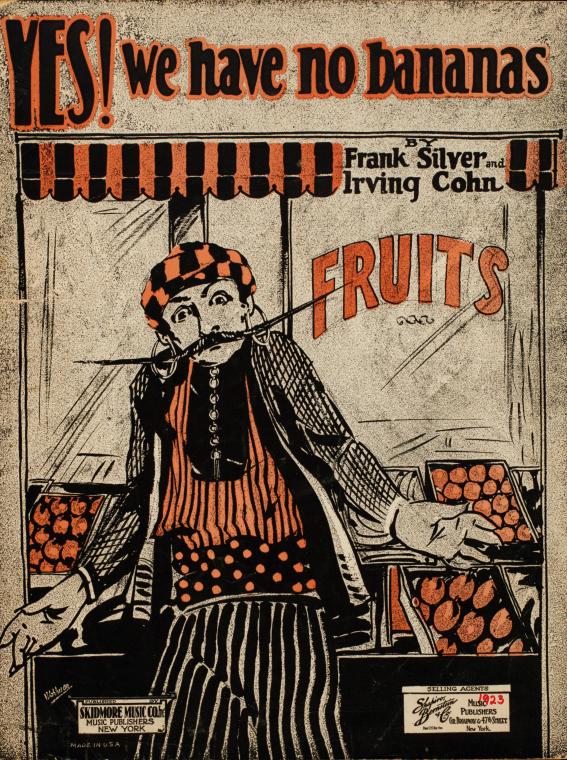

Most of Rogers’ humor was highly topical, focusing on recent news stories. In a collection of essays published in 1924, Rogers discussed one of the most popular songs of the time, “Yes! We Have No Bananas.” The song itself is a piece of voice appropriation. Written by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn in 1923, its title appears to have been taken directly from the words of a Greek immigrant fruit vendor from whom Cohn bought fruit (Wichmann 2022). There was a banana shortage at the time due to crop failures in Central America, and the vendor is portrayed as trying to sell customers everything but bananas. In case anyone was slow to get it, the sheet music was illustrated with an image that made it clear that the song carried a hint of exoticism. (See figure 6.21.) The fruit vendor is presented as a Mediterranean immigrant, but not specifically Greek. The same artist drew a very similar figure to illustrate a song that was directly identified as Italian-themed.

Enter Will Rogers. By over-praising it, he pokes fun at the dominant culture’s embrace of voice appropriation. By directly quoting it, he engages in content appropriation from the dominant culture. By mixing together two voices — the voice of the song’s character, and his own — his essay is a clear case of dialogism. He enters (but does not mention) the then-current debate about adopting the “Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem, proposing that a song written at the level of “Yes! We Have No Bananas” should be selected. Instead of naming it, he references the “Star-Spangled Banner” indirectly, as a militaristic song that is associated with the dominant culture’s patriotic priorities in the War of 1812, the Civil War, and World War I.

Excerpt from Will Rogers, “The Greatest Document in American Literature”

The subject for this brainy editorial is resolved that, “Is the Song ‘Yes! We Have no Bananas’ the greatest or the worst Song that America ever had?”

I have read quite a Iot in the papers about the degeneration of America by falling for a thing like it. … I claim that it is the greatest document that has been penned in the entire History of American Literature. And there is only one way to account for its popularity, and that is how you account for anything’s popularity, and that is because it has merit. Real down to earth merit, more than anything written in the last decade. The world was just hungry for something good and when this genius come along and got right down and wrote on a subject that every human being is familiar with, and that was vegetables, bologna, eggs and bananas. Why, he simply hit us where we live. … You see, we had been eating these things all our lives but no one had ever thought of paying homage to them in words and harmony. … If we had had a man like that to write our National Anthem somebody could learn it. It wouldn’t take three wars to learn the words. …

This boy has got the stuff. Get this one and then read all through Shakespeare and see if he ever scrambled up a mess of words like these,

“Try our walnuts and CO-CO- nuts, there ain’t many nuts like they.”

Now just off-hand you would think that it is purely a commercial song with no tinge of sentiment, but don’t you believe it. Read this:

“And you can take home for the WIM-mens, nice juicy per-sim-mons.”

Now that shows thoughtfulness for the fair sex and also excellent judgment in the choice of a delicacy. Then there is rhythm and harmony that would do credit to a Walt Whitman, so I defy you to show me a single song with so much downright merit to it as this has.

You know, it don’t take much to rank a man away up if he is just lucky in coining the right words. Now take for instance Horace Greeley, I think it was, or was it W. G. McAdoo, who said “Go West, young man.”‘ Now that took no original thought at the time it was uttered. There was no other place for a man to go, still it has lived. Now you mean to tell me that a commonplace remark like that has the real backbone of this one:

“Our Grapefruit I’ll bet you, is not going to wet you, we drain them out every day.”

Now which do you think it would take you the longest to think of, that or “Go West, Young Man”? … Now what was original about that? Anyone who had been in one could have told you that, and today he has one of the biggest statues in New York. According to that, what should this banana man get? He should be voted the Poet Lariet of America.

Now mind you, I am not upholding this man because I hold any briefs for the songwriters. I think they are in a class with the After Dinner speakers. They should be like vice used to be in some towns. They should be segregated of to themselves and not allowed to associate with people at all, and should be made to sing these songs to each other. … But when one does come along and display real talent as this one has proven, I think he should be encouraged. Some man said years ago that he “cared not who fought their countries’ wars as long as he could write their songs.” But of the two our songs have been the most devastating. …

I would rather have been the author of that banana masterpiece than the author of the Constitution of the United States. No one has offered any amendments to it. It’s the only thing ever written in America that we haven’t changed, most of them for the worst.