1 Art Appropriation and Cultural Appropriation

Theodore Gracyk

Chapter Goals

- Define appropriation in in a descriptive, non-evaluative way

- Understand that appropriation is common in the arts

- Understand major types of artistic appropriation

- Define culture

- Understand that cultural identities are complex

- Define cultural appropriation

1.1. Appropriation: The Basic Idea

Put simply, to appropriate is to take something and to claim it as one’s own.

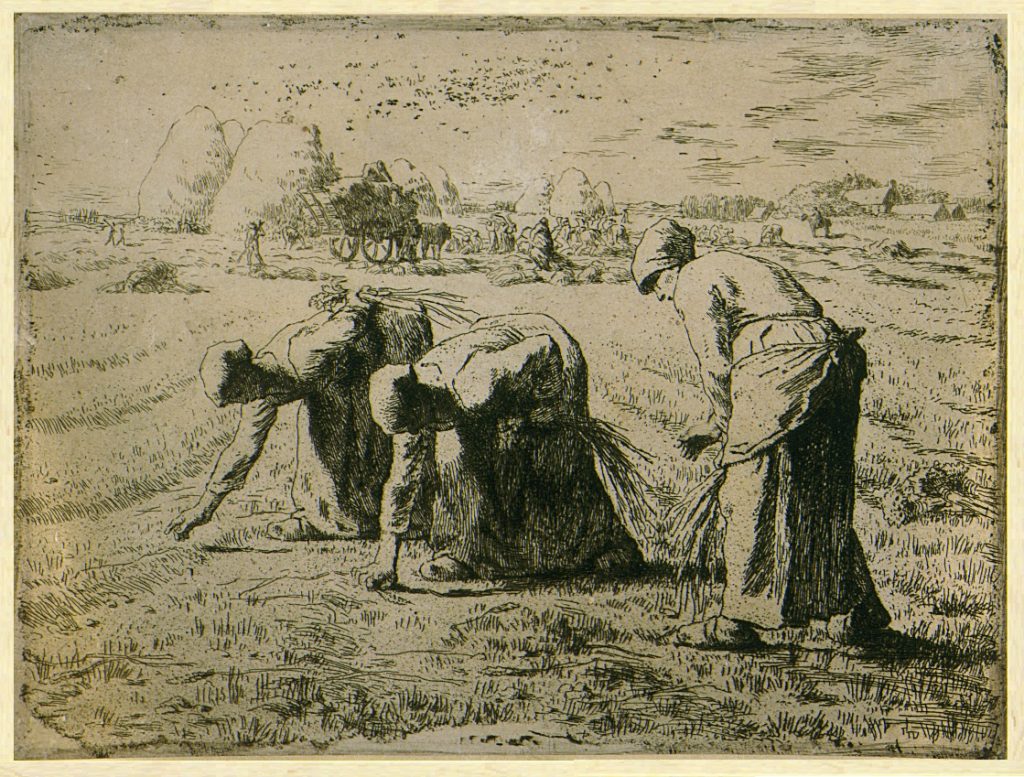

In a famous image created by Jean-François Millet in 1855, three peasant women search for wheat in a field after the crop has been harvested. They are gathering food that would otherwise go to waste. Their activity gives the image its title: “The Gleaners.” (See figure 1.1.) The women illustrate appropriation: they are engaged in the ancient practice of appropriating crops that remain after the harvest. The previous day, the wheat belonged to the farmer. Today, they are permitted to take whatever they can find.

There are many ways to appropriate something. Someone might buy it, or steal it, or take it because no one else has made a claim to it. It might be land or a physical object, and someone takes control of it and makes it their own tangible property. Or someone could just use a vacant building without asking permission: squatting is a mode of appropriation.

While squatting is a morally questionable activity, this chapter does not discuss which of these acts of appropriation are misappropriation, that is, wrongful taking or use. In order to provide an overview of the basic concept, ethical issues are delayed until later in the book. Throughout this book, phrases such as “cultural appropriation” and “voice appropriation” are used in a descriptive, non-evaluative way.

Appropriation frequently involves taking material to use when making something else. Presumably, the wheat is gathered to make flour and then to bake bread. Moving to a larger scale, many ancient ruins are in bad shape because local people took old buildings apart to use the materials in new buildings. For example, the three great pyramids at Giza, Egypt, were white when they were new. They had an outer layer of white limestone. However, most of this outer layer was stripped off in the 14th century, hauled ten miles north to Cairo, and used in the construction of new mosques. In other words, the pyramids are now light brown in color because their surface layer was appropriated. And, of course, this was many centuries after the contents of their burial chambers were appropriated, that is, looted by thieves.

However, appropriation is not limited to land and physical, tangible things. People can buy, borrow, and steal ideas. This also extends to appropriation of the mode of expression of those ideas. Famously, the cubist art movement arose when Pablo Picasso appropriated the appearance of West-African masks for the faces of two of the women in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). However, appropriation of a design or mode of expression frequently separates it from its original meaning. Picasso copied the designs for his own purposes, eliminating their religious significance and distorting what these masks meant to the people who made them.

The Italian painter and sculptor Amedeo Modigliani moved to Paris at about this time. He, too, became interested in the art of West Africa, and there was a noticeable change in his style. He studied and sketched many African masks. Soon afterward, the faces of his portraits displayed a style appropriation from these sources. (See figures 1.2 and 1.3). The appropriation is clearly evident in the stretching of the faces, the long, thin noses, and the vacant, almond-shaped eyes.

This book itself includes many appropriations. Some of the text in some chapters is derived from other open source books. In order to provide Figure 1.1, an existing image from a museum website has been recycled to show Millet’s etching. It is straightforward content appropriation. As with Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, these appropriations of text and images are non-tangible.

In contemporary society, designs and other original expressions of an idea are generally protected as intellectual property. The right to control and profit from one’s original expression of an idea is associated with copyright protection or patent protection. Generally, these “ownership” protections for intellectual property expire after some fixed length of time and the design or the expression of an idea then enters public domain. Public domain works are ones that anyone can appropriate without seeking permission or paying for their use. Ironically, an image of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon does not appear here because it remains under copyright until 2044.

Story-telling is another common field of non-tangible appropriation. Stories are frequently appropriated and rewritten. William Shakespeare’s play Tragedy of Macbeth fictionalized a true incident in Scottish history, and then the play was appropriated and rewritten to become Akira Kurosawa’s film Throne of Blood (1957). Musical appropriation is also common. The Beach Boys’ first nation-wide hit was the song “Surfin’ U.S.A.” (1963). Although Chuck Berry never wrote about surfing, the music of Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen” (1958) was appropriated for “Surfin’ U.S.A.” and Berry successfully demanded the songwriting credit and all royalties.

The lesson here is that the contrasting cases of gleaning stalks of wheat and rewriting the words to “Sweet Little Sixteen” illustrate a basic contrast between tangible and non-tangible appropriation. What they have in common is that, either way, something that already exists is taken. Sometimes there is compensation for doing so, but sometimes there is not.

This book focuses on non-tangible appropriation in American culture. More specifically, the focus is on appropriation of cultural activities and products that we recognize as art, including the popular arts.

1.2. Art Appropriation

In much the same way that something physical can be appropriated and then used to make something new, ideas and their expression can be appropriated and used to create new cultural products, designs, and intellectual property. This is extremely common in the arts. For example, a visual artist may appropriate a story from one source and a design idea from another source and, combining them, create a unique picture. This is art appropriation.

To get started, here is a simple and obvious example. The art of printmaking flourished in Japan in the 18th and 19th centuries. For much of that time, the publishing industry did not operate with copyright laws of the kind we have today. For that reason, together with a general cultural acceptance of copying images in the production of new ones, original print designs were often “borrowed” by other print artists. It should be noted that Japanese print artists of this period did not make any physical prints themselves. They designed new prints by making line drawings. They sold the drawings to print shops, and the shops created the printing materials and then produced the physical prints. For purposes of simplicity, references to these prints routinely downplay the extent to which printmaking was a collaborative process As was the case when they were produced, the artist who made the basic drawing receives credit for the print.

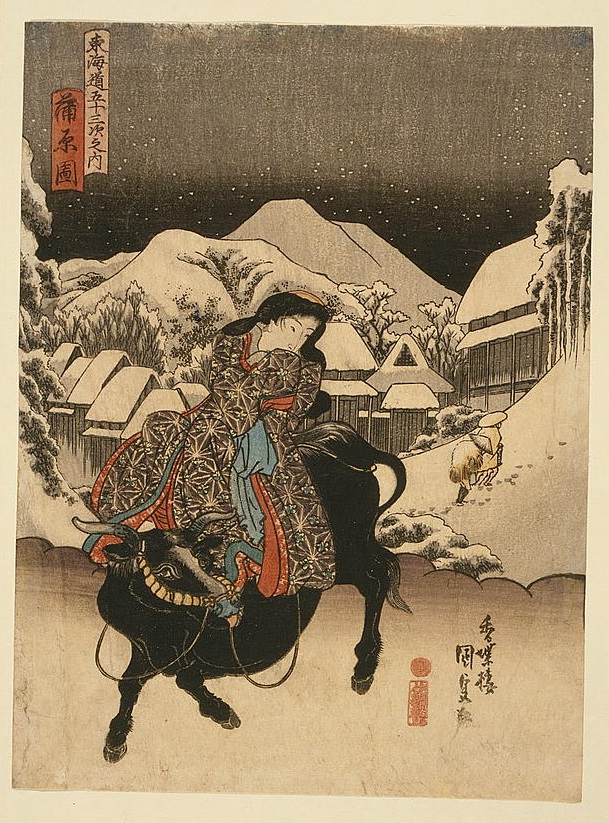

In 1833–1834, Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige designed a revolutionary and popular series of prints that illustrated landmarks along a major travel route, the Tokaido road. One of the best known of these prints is the sixteenth print in the series, Kanbara. It shows a small village during a deep snowfall. (See figure 1.4.) A few years later, Utagawa Kunisada appropriated Hiroshige’s designs from the Tokaido prints and used them as backgrounds for his own series of Tokaido prints. (See figure 1.5.) The two artists share the name “Utagawa” not because they are related, but because it indicates that they were both students trained in the Utagawa school or workshop. These are their professional names. Kunisada also claimed the name Toyokuni the 2nd, and Hiroshige often signed himself Ichiyūsai Hiroshige.

No one in 19th-century Japan would have seen anything wrong with Kunisada’s appropriation from Hiroshige. In fact, there were no hard feelings between the competing commercial artists and they later worked together as a team to design a new “two brushes” set of Tokaido prints.

This example shows that different cultures have different attitudes about artistic originality and appropriation. It is a mistake to assume that universal standards govern what counts as misappropriation.

In most of today’s world, this level of direct appropriation from a competitor would likely lead to a lawsuit if it was not negotiated and approved in advance. For example, there is a famous image of President Barack Obama by the artist Shepard Fairey, with the word “hope” at the bottom. Fairey created it by appropriating a photograph by Mannie Garcia. Because the photo was incorporated without prior permission, Fairey was sued for copyright infringement. Fairey responded that because he had changed the image in several ways, he was operating at a level of appropriation that falls within the “fair use” doctrine. He claimed that he had transformed what he had appropriated enough to be an original artwork. In the end, Fairey avoided a court trial on the matter by reaching a settlement. While we did not get to learn whether the American courts would endorse his appropriation as fair use, copyright does not prohibit all forms of direct artistic appropriation, especially for older art and for the performing arts. All of the visual examples that appear in this chapter are of older works that can be reproduced (that is, appropriated) without payment or prior permission because the art is old enough that it is not subject to copyright protection. But, of course, the fact that some appropriations are legal under U.S. or international law does not mean that is morally right to appropriate what others have created.

1.3. Cultural Appropriation

The main focus of this book is cultural appropriation, a version of artistic appropriation that is only present when two cultures interact. Cultural appropriation occurs when someone appropriates from a different culture than their own.

Cultural appropriation can be divided into several distinct categories, and the remainder of this chapter outlines these variations. The current section and the next one (1.3 and 1.4) will introduce the basic idea of cultural appropriation, the next after that (1.5) will expand on the idea of culture that is being used here, and then the remaining sections will go into more detail about the varieties of cultural appropriation.

Put most simply, cultural appropriation is appropriation of cultural products and practices by people who are “outsiders” to that culture. It is intercultural appropriation. It happens whenever people take from or imitate the cultural products of another culture. Showing the practices of another culture in pictures and stories can also be a form of cultural appropriation.

Not all appropriation is cultural appropriation. A great deal of art appropriation is “internal” to a society. When Kunisada copied Hiroshige, the two print designers were working within the same society and culture (Edo-era Japan). So, although Kunisada was engaging in art appropriation, it was not cultural appropriation. On the other hand, appropriation of Hiroshige’s designs soon spread beyond Edo-era Japan and continues even now. Today, there are bath towels, shower curtains, coffee mugs, and yoga mats decorated with Hiroshige’s “Kanbara.” Whether the production of these items is cultural appropriation depends on who is making them, and to whom they market them. If the yoga mat is being produced by a Japanese firm for sale in Japan, that use is a continuation of Japanese cultural heritage and not cultural appropriation. However, when a twentieth-century American designer appropriates the “Kanbara” image to sell products to an American market, that is cultural appropriation. There are many examples of this, such as the cover design for the music album Pinkerton (1996) by the American rock group Weezer.

Cultural appropriation is an ancient practice and has probably taken place since early societies split off into distinct cultures. Physical appropriation of culture is the simplest type to understand, so it will once again serve as the starting point for better understanding when appropriation is, and isn’t, cultural appropriation.

When archeologists open up ancient burial sites, one of the goals is to learn about the lives and social practices of ancient peoples. For example, large mounds on an estate in east central England turned out to be a medieval burial site. It has been named Sutton Hoo, using old English to designate the mounds and location. The most remarkable thing about Sutton Hoo is that one person was of such importance that his grave consisted of an entire ship, hauled inland and buried under a huge mound of earth. The grave also contained weapons, household items, and jewelry. Another surprise was that these items proved that, long after the collapse of the Roman Empire, eastern England remained connected to trade routes that reached across the world (Williams 2011). The grave contained Merovingian coins (from present-day France), silverware from the eastern Mediterranean, and a shield decorated with jewels that came from Sri Lanka (southeast of India). We know, therefore, that the wealthy class of a small medieval kingdom in England did not function in isolation. Its cultural products included tangible appropriation from both near and far.

The Sutton Hoo case is not remarkable except that archeologists were surprised about the level of wealth buried there. All except the most isolated societies engage in trade that results in intercultural tangible appropriation. For example, many of the Indigenous peoples of North America used porcupine quills to create elaborate decorative patterns on shoes, clothing, cloth bags, and many other items. Because they are hollow, the quills can be threaded like beads, and they were dyed various colors by using plants to produce natural dyes. However, the arrival of colonial settlers and their westward expansion led to increasing trade between the colonizers and Indigenous Americans. Small glass beads became a staple of intercultural trade. These beads traveled to the American Great Plains from Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. By 1850, imported beads and traditional quill work were increasingly intermingled. (See figure 1.6.) By 1900, beads were so inexpensive and widely available that the use of quills almost vanished from Indigenous handwork, only to be revived later in a conscious return to traditional culture.

Next, consider two specific objects that are in the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (“The MET”). One is from 13th-century France, and the other is from what is now the center of the continental United States. (See figure 1.7 and figure 1.8.) Here, the tangible appropriation is the transfer of ownership that brought each of them their shared home in New York City.

Coming across these two objects in different areas of the same museum, it might not be obvious that this silver hand and fringed shirt have something important in common. They are both sacred objects within the home cultures that produced them. They both have religious as well as artistic importance. The Medieval French silver hand is not simply a sculpture. It is a reliquary, which is a container created to hold relics (in this case, physical remains) of a Roman Catholic saint. It would have been placed on a church altar during religious services. The leather shirt is a war shirt of the Crow Nation, an Indigenous people whose traditional homeland is spread across present-day Montana and Wyoming. It was made to be worn during special ceremonies. Human hair from tribal members contributes to the shirt’s fringe, signifying that the power of the warrior who wears it will be used to protect the tribe. (The existing threat to the tribe when it was created was the United States army.)

We do not know precisely how either object found its way to New York. In each case, it was eventually donated to The MET by a wealthy art collector. In each case, this transfer is art appropriation, where a religious artifact has been acquired for display as art. In the case of the French reliquary, we might allow that the United States has an artistic culture that is deeply indebted to French culture, and so its transportation from France to New York might be nothing more than a case of art appropriation. However, that is not plausible in the case of the war shirt. Traditional Crow culture is clearly distinct from the European-collecting culture that developed the art museum as a place to display collections of art. They are distinct societies and this appropriation is tangible cultural appropriation. According to Crow custom, no one in the community had the authority to transfer the shirt out of tribal control. It could only have become the property of an art collector and then the museum through some initial act of theft. (Imagine a private individual claiming to own the Statue of Liberty and offering it for sale! No legitimate transfer of property could happen that way.) According to Crow tradition and living representatives of the tribe, the shirt should not be displayed and should be returned to the Crow Nation.

In many cases, cultural appropriation from traditional and Indigenous peoples involves trafficking in stolen goods. In the United States, museums and institutions supported by federal funding are now required to locate and return any Indigenous human remains and sacred objects in their possession. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 was originally designed to address museum collections containing human remains and artifacts stolen by looters and grave robbers. However, the law has a broad description of which tangible objects should be returned. The law requires the return of any “object having ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself.” The Association on American Indian Affairs has asked The MET to return the war shirt to the Crow Nation. However, because the war shirt was a “private gift” to The MET, the museum is not legally obligated to return it, and they have not done so. The museum’s ongoing possession and display of the shirt are directly contrary to the cultural beliefs and values of the people who created it. In this manner, cultural appropriation often leads to ongoing disrespect for the integrity of Indigenous peoples.

1.4. Visual Appropriation

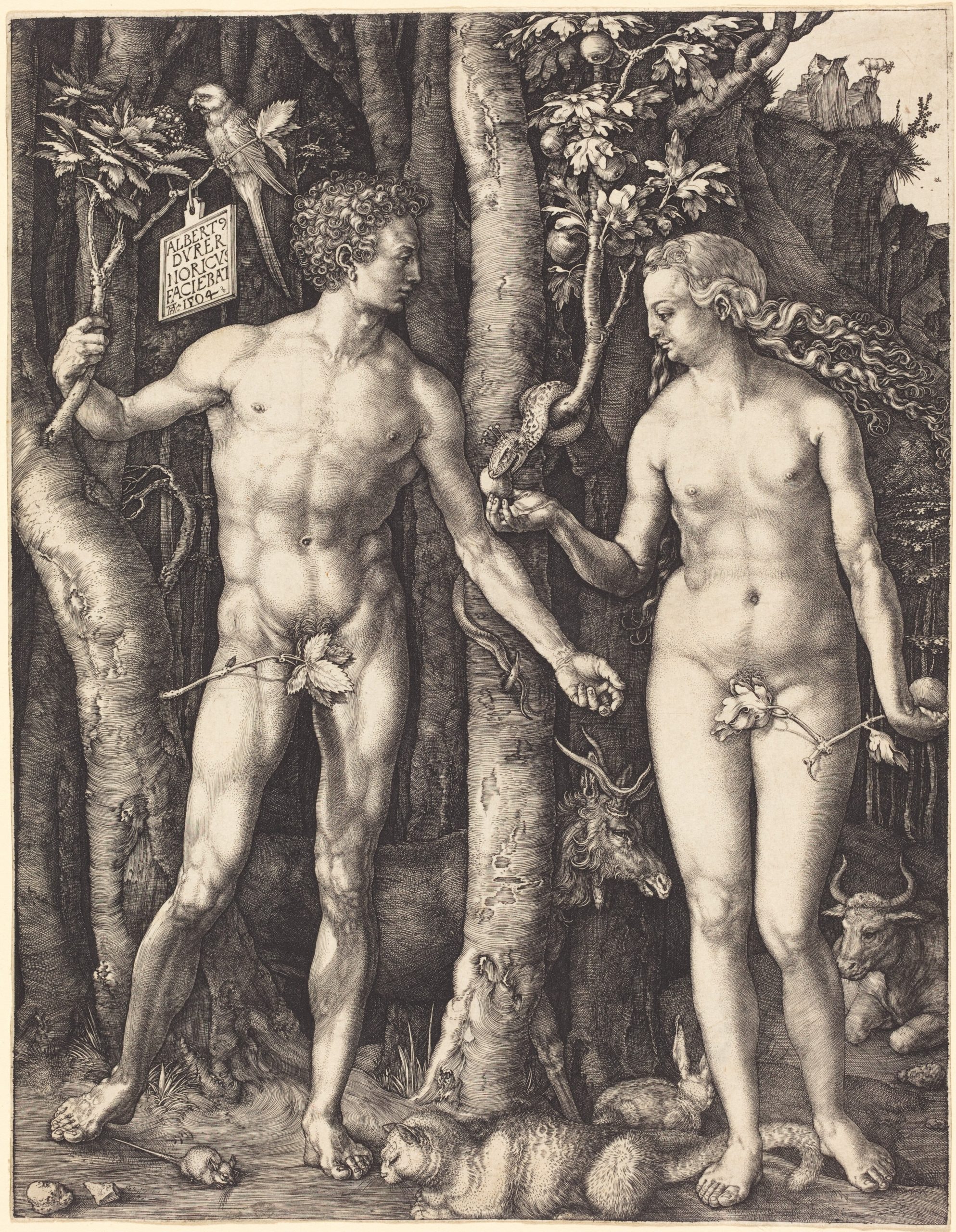

Art history offers countless examples of cultural appropriation through copying rather than physical transfer. A famous example is a print created by Albrecht Dürer in 1504, portraying Adam and Eve. (See figure 1.9.) A life-long Roman Catholic who was sympathetic to the Protestant Reformation, Dürer produced many famous images of Christian subject matter. At the same time, he was working at the height of the artistic and cultural movement that we know as the Renaissance, during which European artists looked back to earlier non-Christian achievements for inspiration and guidance. In this print, Dürer appropriated the poses of two ancient statues. Eve is modeled on a Venus statue from pagan Greece, and Adam is modeled on an Apollo statue from pagan Rome. One is a goddess, the other a god. (See figure 1.10.) Here we have a straightforward case of non-tangible appropriation that is also cultural appropriation.

Comparing Dürer’s print with the two statues, notice the basic stance of the figures. In each case, the weight of the body is one one leg (foot firmly planted). The other leg is bent at the knee and the heel of the foot is off the ground. This pose, used in many ancient statues, is called contrapposto or “counterpoise.” It produces a slight curve of the whole body, making the figures more dynamic and alive. In this case, it creates the effect of Adam and Eve leaning in toward one another in an intimate way. But Dürer has not simply appropriated the ancient technique of contrapposto . Look at Adam’s uneven shoulders, the turn of their two heads, and Adam’s hair. Adam and Eve are clearly modeled on, and so appropriated from, these two specific statues.

There was no significant connection between ancient Mediterranean culture and the culture of Bavaria, where Dürer was born and raised. The area had once been part of the Roman Empire, but Germanic culture had always remained distinct from that of the Roman conquerors. Furthermore, it had been more than a thousand years since the empire had collapsed. Today, many people assume that there was ongoing cultural continuity between ancient Greece and Rome and later European culture. However, the connection back to those ancient Mediterranean cultures is largely a product of events of Dürer’s own time. Artists and intellectuals revived the connection through appropriation. Several generations of Renaissance intellectuals and artists made a conscious effort to infuse ancient pagan culture into their own Christian societies. These appropriations from the past transformed European culture. (This is why they referred to their active appropriation of the past as a “Renaissance” or “rebirth.” They understood that Greek culture and Roman culture were dead cultures and they wanted to make them “live” again.) Furthermore, Dürer was not copying what was happening in other visual art in Bavaria at the time. Art historians have established that he was a trendsetter in being the first artist in southern Germany to embrace and promote Renaissance humanism in visual art (Price 2003). He was leading the way among his immediate Bavarian peers in selecting Apollo as a model for male figures in Christian art.

Therefore, Dürer’s Adam and Eve is not simply art appropriation. It is a case of cultural appropriation. A new artwork was created by appropriating from the art of other cultures.

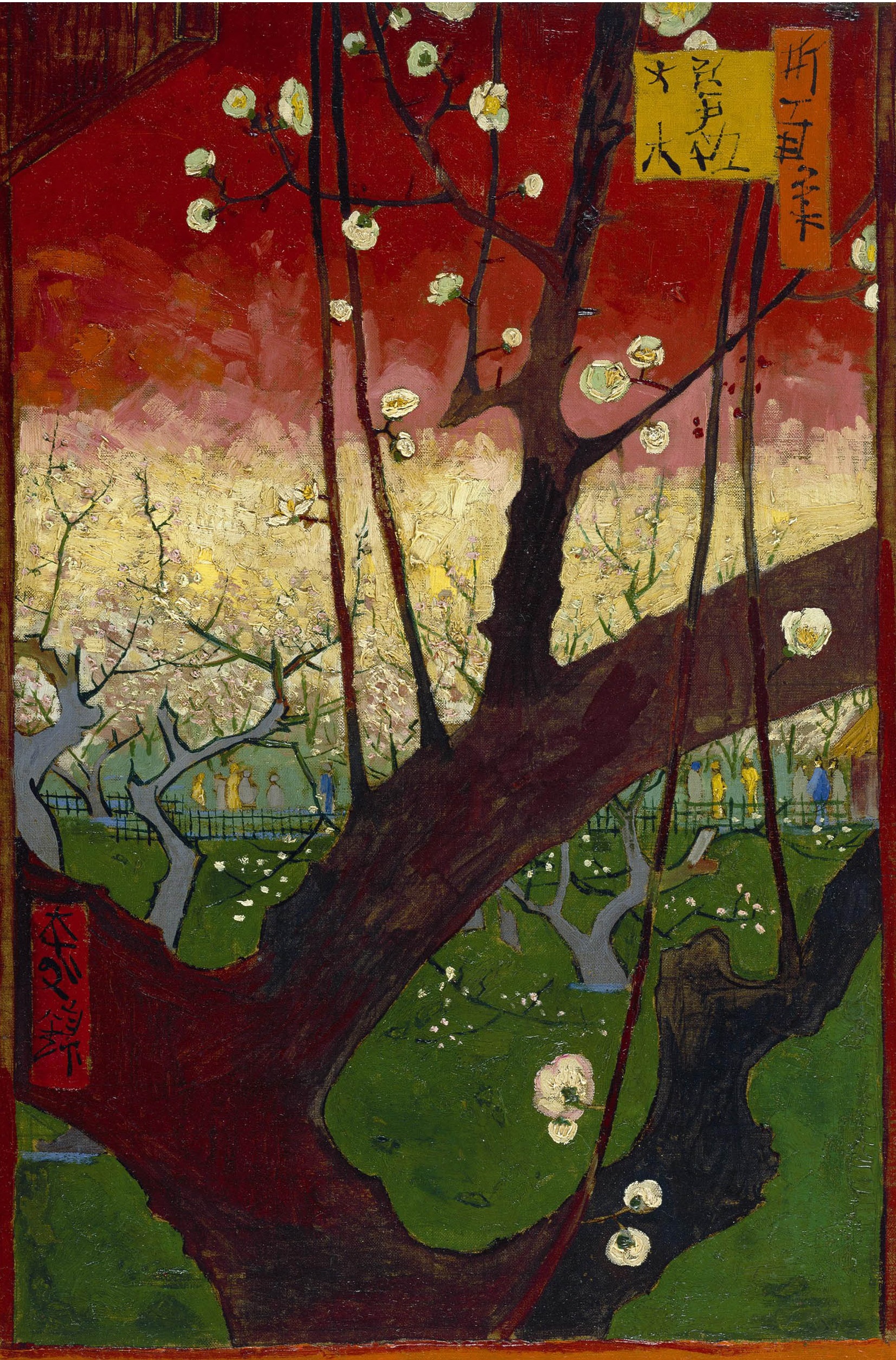

Another example of cultural appropriation is Vincent van Gogh’s rendering of a print by Hiroshige. (See figure 1.11.) Hiroshige established his reputation in Japan by creating the Tokaido series that Kunisada appropriated. At the end of his life, Hiroshige’s final achievement was a larger set of prints called One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856–59). Edo was the traditional name for present-day Tokyo. Unfortunately, Hiroshige died during a cholera epidemic in 1858, leaving the series unfinished. Just a few years earlier, the United States sent warships and used threats to get Japan to enter into an open trade agreement. Negotiations were completed in 1860, and Japanese prints by Hiroshige, Kunisada, and other artists flowed out of Japan in staggering numbers. Many were exported to Europe, where van Gogh (despite his poverty) owned more than 650 of them (Rüger and Vellekoop 2018). Copies of some of them appear on the walls and backgrounds of indoor settings in van Gogh’s later paintings. In in at least two cases, he made detailed copies of prints by Hiroshige. One of these was Plum Estate, Kameido, the 30th print in the one hundred views of Edo series. Like several other designs in this print series, Plum Estate displays a high level of originality. Hiroshige fills the image with a close-up of one uniquely bent plum tree while reducing everything else to the background. The time depicted is early spring: the plum trees are flowering. Crowds have come to view them from the fenced path that cuts through the orchard. Van Gogh carefully copies Hiroshige’s composition. However, he changes the colors, darkening the foregrounded tree and the red sky. Hiroshige’s pleasant sunset becomes something much more dramatic.

So, van Gogh carried out cultural appropriation in two distinct ways: he bought imported Japanese prints (tangible appropriation), and then he copied all or parts of some of them.

Van Gogh did not hide his artistic debt to Hiroshige. By copying the Japanese system of text in boxes within the print, van Gogh makes it clear that he is appropriating from another culture. (In the original, the title and series title are the two boxes in the upper right, and the artist’s name is at the left. However, van Gogh did not attempt to make an accurate copy of the original Japanese characters.) In letters to his brother, van Gogh praised the directness of the Japanese approach and said that all his later work was modeled on the design principles and “feeling” of Japanese art (van Gogh, letter of 10 September 1889). So van Gogh’s appropriation was both very specific, copying content, and more general, adapting design principles and artistic style.

Many other European artists of the time also studied Japanese prints and appropriated their designs. This was especially true in France. Henri de Tolouse-Lautrec, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and many other artists in the late 19th century appropriated subject matter and designs from Japanese prints. However, some of these artists were less open about their reliance on cultural appropriation. Until recently, art history textbooks often praised them for their originality without explaining that some of their most striking designs were appropriated. For example, Mary Cassatt made a set of ten prints that were inspired by her study of Japanese prints. The Bath, in particular, recreates a mother-child scene that appears in many Japanese prints. (See figure 1.12.) She also adopts design principles that originated in Japanese portrait prints: the basic picture is a black line drawing, the figures occupy most of the image, only a few colors are used, and there is little else shown beyond the primary subject. Cassatt has engaged in a double appropriation in The Bath: there is style appropriation (how it’s drawn), and there is content appropriation (what is pictured). This distinction between content and style is explained in greater detail below, in the section 1.6.

1.5. What Is Culture?

The previous section introduced the idea of cultural appropriation without explaining what is meant by culture. The first thing to note is that the word “culture” is being used in an inclusive and nonjudgmental way. Every person lives in an ongoing relationship to one or more cultures. Other than young infants, no one is uncultured. Among adults, no one is really “more” cultured than anyone else.

Unfortunately, the term “culture” is frequently used in a judgmental way. It is used to endorse the values and modes of expression of a society’s privileged class. This elitist, exclusionary approach is associated with Matthew Arnold’s book Anarchy and Culture (1875). Famously, Arnold limits culture to “the best which has been thought and said” (Arnold 1875, p. x). He also describes it as “the sweetness and light of the few” that aims at the improvement and perfection of the masses (Arnold 1875, p. 43). For Arnold, nothing negative belongs to culture. On this approach, privileged groups have historically, and even now, denied that non-dominant groups possess their own culture. In the past, denials of cultural legitimacy were often expressed by the term “uncivilized.” An elitist approach to culture is often used to justify oppression in the name of “helping” groups identified as uncultured and uncivilized. Some examples of this sort of cultural elitism are introduced in the next section.

The Japanese prints discussed earlier demonstrate why it is a mistake to think of culture in an elitist way that limits culture to a society’s upper classes. When they were new, the prints that impressed and inspired van Gogh and Cassatt were not the “sweetness and light” of Japanese society. In fact, Edo-era Japanese society did not even classify them as art. A painting on silk could be art, but not a cheap, mass-produced Hiroshige print that was available in book shops and from street vendors. A painting that illustrated a classic poem was art, but not an illustration of peasants trudging through the snow, like Hiroshige’s Kanbara. Consider Japan’s most famous image, Katsushika Hokusai’s print The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831). In Japanese society, art did not portray the lives of low-class commoners like those in The Great Wave, which shows men in boats fighting the waves after hauling their tuna to the market in Edo. In their original time and place, mass-produced prints were part of the entertainment industry of Edo and other large cities. The Japanese viewed these prints as low-status craft objects (Davis 2021, p. 16). They reflected the lives and values of the merchant class, a group that Japanese society placed as the lowest in its ranking of social classes. Although Japanese society did not regard the prints as among their “collective best” achievements, these prints were (rightly!) treated by European and, subsequently, American artists and collectors as central documents of Japanese culture. In hindsight, Japanese society came to agree.

A non-elitist view of culture calls for non-elitist approach to art. In the non-elitist approach to culture used in this book, art includes a society’s treasured fine art, but it also includes popular and disposable art. It includes both Shakespeare’s plays and children’s bedtime stories, the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci and Marvel comic books, the symphonic music of Beethoven and the songs of Taylor Swift, the Statue of Liberty and paper dolls. (See figure 1.13.)

In the past, paper dolls were printed in American newspapers. In many ways, these printed sheets had an original cultural status like that of the prints of Hiroshige, Kunisada, and Hokusai. Like those Japanese prints, the paper dolls were mass-produced for a broader range of people than the paintings and sculptures created for wealthier, socially privileged people. For that reason, people did not regard them as art when they were new. Nonetheless, folk art, popular art, and mass-produced art are a valuable record of the beliefs and values that are widespread in a society. They are part of culture, too. For example, these paper dolls from 1895 are very much a reflection of the dominant culture in the United States. They feature historical figures from England and Scotland, including two who played a role in the English colonization of North America. As such, these particular dolls played a role in carrying the history and traditions of the dominant culture to the children of the emerging middle class of the late 19th century.

So, what is culture?

Art and culture are closely related, but they are not the same thing. Basically, “culture” refers to a distinctive group of people rather than the things they produce.

One culture is distinguished from another by reference to the basic values, behaviors, and beliefs that organize their way of life and provide them with an ongoing, inter-generational group identity. From this vantage point, art is one part of cultural identity. Art is expressive communication that reflects group identity. Communication that conveys information without a significant expressive purpose isn’t art. So, a scientific report or a Wikipedia article isn’t art. In contrast, later chapters of this book treat advertisements, newspaper editorials, and cartoons as art. They are popular art.

This emphasis on expression of group identity differs from what many people assume about art, which is that the arts are important as the expression of individual creativity and self-expression. There are countless books that approach art as individual self-expression. However, that is not the approach taken here. Instead, the emphasis is on how self-identity and self-expression are closely related to group identity. To borrow from an essay by Ralph Ellison, a Black American writer, “Art by its nature is social” (Ellison 1953, p. 38).

Why should we regard art as inherently social? To appropriate a famous metaphor crafted by the poet John Donne in 1623, “No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” Even if it is the case that some art is a display of self-expression, and some artists are more creative than others, no artist produces art in a cultural vacuum. Donne did not invent the language he used to craft this metaphor: his starting point was the English language and its conventions and vocabulary as those existed in the early 17th century.

Donne may have originated the “no man is an island” metaphor, but he is hardly the first person to observe that how people behave and what they believe is influenced by when and where they were born and raised. As Aristotle observed twenty-four centuries ago, humans are social animals. We depend on each other. Human babies have lengthy periods of development in which they learn language and become socialized by those around them. Even for adults, survival is almost impossible without group or social cooperation. Social cooperation puts food on the table, keeps the lights on, and provides for the needs of children and others who can’t fully care for themselves. At the same time, societies have a historical dimension. In raising the next generation, each society passes along values, beliefs, and customs. Some of these social inheritances will be relatively recent in origin. Some persist for many generations. Either way, no group starts from scratch and invents all of its own language, tools, religion, entertainment, and laws. Some of these things are passed along in an organized way, in formal education. Some are learned informally from others in the society by the process of living among, and imitating, the rest of the group.

Culture, then, is group identity based on historical identity. Culture binds a group of people together because their distinctive way of life is shared by, and carried forward from, the previous generation. By definition, culture is shared, learned, and cumulative. None of this means that it remains fixed or frozen. Later generations adapt and modify cultural traditions transmitted in response to changing times and circumstances.

This emphasis on what is learned from the previous generation distinguishes cultural membership from other kinds of group membership. In the modern world, cultural identity frequently relates to national identity, as when we say that Korean culture is different from German culture. However, cultures can cut across national and linguistic boundaries, so that we can speak of the culture of Christianity as distinct from the culture of Buddhism. And since there are both Buddhists and Christians in both Germany and Korea, it is also the case that cultures overlap in interesting and complex ways.

To offer a summary definition, the concept of culture used in this book is captured by James Neuliep’s description of culture as “an accumulated pattern of values, beliefs, and behaviors, shared by an identifiable group of people with a common history and verbal and nonverbal symbol systems” (Neuliep 2012, p. 19). Notice that, aside from common history, the definition is completely neutral about how a group of people might come together and share an identifiable culture. Notice, in particular, that the definition does not assume that the group is a nation or racial group. Culture is not restricted to national cultures and ethnic cultures. Furthermore, this approach is value-neutral. There is no assumption that any culture is better than any other.

Finally, culture is not mutually exclusive. This is especially true at the level of the individual person. The fact that a person has an identity aligned with one distinctive culture does not rule out alignment with another. In multicultural societies, many individuals belong to an ethnic culture as well as one or more regional cultures or subcultures. For example, Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) and Maya Angelou (1951–2014) are two of America’s most famous poets. Setting aside the fact that they lived in different centuries, they are two important representatives of American culture and one can find examples of their writing in any good collection of American literature. However, Dickinson is a White woman from New England, while Angelou is a Black woman who was primarily raised in Arkansas. As American women, they have a degree of shared cultural identity. At the same time, it is clear to anyone who understands American society that these two poets have, and express, different cultural identities. Dickinson belonged to the dominant culture of her time and place. Angelou did not.

To summarize, art is a major element of culture. Every society encodes its culture in its storytelling and its visual and performing arts, and these cultural products provide access to shared practices, beliefs, and behaviors. By examining the full range of art produced by a society, it is possible to get a rich picture of its ongoing way of life. Furthermore, the arts frequently display a culture’s interactions with other cultures. Sometimes this is explicit, where the subject matter is the meeting of different cultures. Sometimes it is less explicit but shows itself in appropriations from another culture. Either way, the arts provide a wealth of evidence about both inter-cultural and intra-cultural social relationships. Patterns of appropriation are especially revealing about cultural attitudes and behaviors that involve group dynamics. Where group dynamics involve oppression and discrimination, works of art and literature and other cultural products will sometimes include a record of the endorsement of those harmful values. Unfortunately, culture is not all sweetness and light.

1.6. Varieties of Non-Tangible Cultural Appropriation

So far, this chapter has distinguished between tangible and non-tangible appropriation. It has also explained why some appropriation is cultural appropriation. However, to understand the full extent of cultural appropriation, it helps to see that intercultural “taking” takes several distinct forms. There are at least five distinct categories of cultural appropriation.

Setting aside the first type, tangible appropriation, there are four distinct kinds of non-tangible cultural appropriation.

1. Content appropriation is taking and reusing preexisting information. This may include (but is not limited to) taking facts, ideas, or stories.

2. Style appropriation is copying a distinctive artistic style from earlier cultural products. Style is found in the distinctive way that elements are combined.

3. Motif appropriation is copying one or more design features, patterns, or symbols from earlier cultural products.

(To give credit, the basic formulations of these first three categories are from the work of James O. Young (2011).)

When the appropriation is by a cultural insider, these three are artistic appropriation. When the appropriation is by a cultural outsider, they are cultural appropriation.

There is a fourth type of non-tangible appropriation, and it is so frequently linked to cultural appropriation that this initial discussion will treat it as such:

4. Voice appropriation is representing someone else in a way that implies insight into their beliefs and values.

Frequently, this involves creating a representation of an individual while using that individual to represent a larger group, so that the ideas and feelings attributed to the one person “speak” for the group. This book will generally focus on cases of voice appropriation that involve representing people of another culture in a way that implies insight into distinctive or important aspects of that culture.

To illustrate what is involved in each of the four types of non-tangible cultural appropriation, here are four new examples.

CONTENT: Content is any information represented, described, displayed, or shown in a picture, text, story, or other communication. Most people get their information from other sources, and therefore content appropriation is extremely common. It occurs whenever one person shares information they have taken from another source. However, the focus here is content appropriation within the arts. For example, the popular “Twilight” books by Stephanie Myers say that a number of central characters are shapeshifters belonging to the Indigenous Quileute people of western Washington state. Myers appropriated the traditional origin story of the Quileute Nation and inserted werewolves (or shapeshifting wolves) into the story, weaving her new material into appropriated legends to create a fictional background story for the “Twilight” saga. As a result of Myers’s changes to the appropriated content, an internet search for word “Quileute” leads almost immediately to the topic of whether the tribe includes real werewolves. For good or bad, the “Twilight” series is built around appropriated content.

STYLE: If content is what is presented, then style is how it is presented, its “mode of expression” (Judkins 2011, p. 134). There are broad, shared styles, such as Impressionism in painting, ragtime in music, and Elizabethan drama in theater. Style can also be highly individualized, so that people who are familiar with van Gogh’s work can tell immediately that a painting displays his distinctive style. Style is especially prominent in music: “only a moment’s exposure (a few seconds of listening) is usually enough for us to identify it” (Judkins 2011, p. 134). In the 1960s, popular music underwent profound changes. Many of the changes arose from the so-called “British Invasion” in which British musicians took over the airwaves, jukeboxes, and sales charts of the American music industry and then much of the rest of the world. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones are the most famous bands in the British Invasion. Both bands practiced content appropriation, “covering” American popular songs and exporting their versions back to the United States. For example, both bands covered Barrett Strong’s 1959 hit record “Money (That’s What I Want).” However, in addition to this content appropriation, both bands learned to perform several different American musical styles and then appropriated these styles for their own original music. For example, the Beatles adopt the sound of close harmony doo wop for “This Boy.” “Back in the U.S.S.R.” blatantly copies the style of the Beach Boys. “Don’t Pass Me By” is clearly indebted to country music. Similarly, the Rolling Stones were initially known for their ability to copy Black American styles, especially blues music. Clear examples of original songs that sound like American blues are “I Got the Blues,” “Stray Cat Blues,” and “All Down the Line.”

MOTIF: A motif is a distinctive pattern, design element, or symbol. Brand logos are common motifs. (Think of the swoosh for Nike shoes and the double arches of McDonald’s.) Motif appropriation occurs when someone repurposes a motif that was already in use by someone else. The state flag of New Mexico has a very simple design. (See figure 1.14.) It has a distinctive, burgundy-red figure on a golden yellow background. Some people might see it as a cross centered on a circle, with the cross consisting of four parallel lines. In fact, the basic design is a traditional sun symbol of an Indigenous group, the Zia Pueblo. The lines are sunrays radiating out, rather than a cross. This symbol is sacred to this Indigenous community. It became known to cultural outsiders because it appeared on a sacred pot that was physically removed from the pueblo in the late 19th century and then the pot was displayed in nearby Santa Fe. Some years later, individuals within the dominant White culture appropriated the design and entered it into a contest for the design of the state’s flag. As often happens, minor changes were made during the appropriation process. Today, this modified Zia sun decorates jewelry, clothing, tourism advertising, tattoos, and even the faces of clocks. Many Indigenous people of New Mexico find this motif appropriation to be highly offensive and the tribe has been fighting (unsuccessfully) for legal control over their Zia sun symbol.

VOICE: Last but not least, voice appropriation occurs when an outsider represents the cultural perspective of another culture. As an example, consider a postage stamp issued by the United States in 1930. (See figure 1.15.) Many postage stamps are issued to commemorate anniversaries of important events, and these stamps often appropriate images from the time of that event. The 1930 stamp was issued to commemorate the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the arrival of the Puritan “pilgrims.” The stamp commemorates the beginning of British colonization of present-day New England.

The picture in the center of this stamp is a copy of the official seal of the government of the colony. (To this extent, we have content appropriation.) The seal was designed in 1629, before the colonizers left England on the Mayflower. It pictures an adult male who fits an English stereotype of the Indigenous peoples they expected to encounter. The man is almost naked. He holds his arms wide so that his weapon is non-threatening, an idea reinforced by having the arrow in his other hand turned down to the ground. A ribbon of speech is above and around his head. Although it is hard to read when reduced to a stamp, the ribbon contains the same words as the original seal: “Come over and help us.” Obviously, “come over” is an invitation to cross the Atlantic Ocean from England. The “help” that is requested is less clear. However, the Puritans saw themselves as divinely charged to spread their version of Christianity into North America, so the message suggests that the man is asking the English to bring Christianity to his people.

The government seal of the colony literally puts words into the mouth of the man in the picture. This an extremely clear example of voice appropriation. Outsiders have created a symbol in which a man welcomes them by asking them to bring “help.” He is being presented as a representative of whatever people the Puritans would displace when they founded their colony. (It would turn out to be the Wampanoag Tribe of present-day Massachusetts, the “People of the First Light.”) The image implies that Indigenous people saw themselves as culturally deficient and in need of reform and change that could only be brought about by the arrival of the European colonizers. The image purports to tell us what the Wampanoag people thought about their own situation at this time. In this English fantasy, Indigenous people welcomed English colonization and cultural change.

Many scholars have observed that voice appropriation is most often a kind of voice replacement. As historian Caroline Dodds Pennock puts it, it is the distorting practice of “filtering” another culture through “ventriloquism” (Pennock 2023, p. 214). In this case, an imaginary man speaks for an entire people. A “voice” created by outsiders replaces genuine representatives of the culture so that actual participants of the culture are silenced or ignored.

Reproducing the colony seal on the stamp compounds the original voice appropriation. The postal service could have used some other image. In selecting and republishing this seal, a U.S. government agency revived a long-forgotten voice appropriation. The stamp spread the fantasy that Indigenous peoples of North America had welcomed colonization.

Appropriation within an Indigenous framework

The Washoe (or Wá∙šiw) Tribe are located in present-day Nevada. Like many Indigenous Americans, the Washoe people created decorated baskets for storing food and other items.

Baskets made in the early 20th century by Louisa Keyser, a Washoe woman, are highly prized and can sell at auction for more than a million dollars each. Keyser originated a unique combination of decoration and weaving style. (See figure1.16.) When she was making the baskets, she had an arrangement to market them through a White couple who ran a store in Carson City, Nevada. They falsely advertised the baskets as the work of a Washoe “princess” and claimed that tribal custom ensured that she alone could make baskets of this type. About 150 of her baskets are known to survive.

In fact, all of the claims that were originally made to sell the baskets were false. She was not a “princess” and there was no tradition that restricted others from copying her work. Furthermore, her baskets were not strictly the products of Washoe tradition (Tracy 2023). The shape and stitching of her baskets were unique among the Washoe people at that time, but only because she appropriated the shape from the baskets of the nearby Maidu Tribe and appropriated the stitching technique from the baskets of the Pomo Tribe. Ironically, the baskets are highly decorated because they were intended to be sold to tourists and collectors. Since they would not be worn down or destroyed through daily use, they were more highly decorated than traditional Indigenous baskets of that region.

Indigenous people saw nothing wrong with Keyser’s appropriations and departures from tradition. Anthropologists point out that our contemporary concerns about the ethics of appropriation would be completely alien to Washoe culture (Tracy 2023). In fact, once Keyser started to make money with her baskets, other Washoe basket weavers appropriated from her.

1.7. Voice Appropriation in Literature

Voice appropriation is common in literature. Consider the example of The Vanishing American, a novel by one of the United States’ most popular authors, Zane Grey. More than 100 films have been based on his books. Born and raised near Columbus, Ohio, Grey was educated at the University of Pennsylvania and he was a dentist before eventually pursuing a career in fiction writing. Grey is best known for his many books on a topic that was far from his Ohio upbringing: the American West.

As was common at the time, The Vanishing American was published in installments in a popular magazine that reached millions of readers before it was issued in book form. Grey aims to offer a sympathetic account of the mistreatment of the Navajo Nation (their Diné Bikéyah). He does this by focusing on the personal struggles of the fictional character of Nophaie, who has returned to his tribal homeland after a “White” education and success in college football. In 1922, most readers would have readily identified Nophaie with Olympic gold medalist Jim Thorpe, a member of the Sac and Fox tribes who had just retired from professional baseball. Readers who understood that Thorpe was Grey’s model would transfer Nophaie’s views to Thorpe, lending them credibility by association with a sports celebrity.

The following passage is one of many where the fictional Nophaie offers his thoughts:

Excerpt from Zane Grey, The Vanishing American

“The Indian in me speaks,” he soliloquized. “It would have been better for me to have yielded to the plague. That hole in the wall was my home—this valley my playground. There are now no home, no kin, no play. The Indians’ deeds are done. His glory and dream are gone. His sun has set. Those of him who survive the disease and drink and poverty forced upon him must inevitably be absorbed by the race that has destroyed him. Red blood into the white! It means the white race will gain and the Indian vanish.” (Grey 1925, p. 294)

A few lines later, Grey describes Nophaie’s words as an expression of “the misery of his race.”

Here, Grey goes beyond an association of Nophaie with Thorpe. Although Grey is an outsider to the culture he represents, he uses Nophaie to speak on behalf of “the Indian,” as though racial identity ensures that Nophaie is the voice of many Indigenous peoples. So, Grey is not simply telling a story here. He wants the story to represent real people and real events, and he purports to represent a whole culture by giving voice to one individual. As discussed later in this book, in Chapter 5, Grey is giving new expression to a long-standing idea of the dominant culture, the idea that Indigenous peoples are a vanishing race and cannot coexist with a more advanced dominant culture. Like the Massachusetts Bay Colony seal discussed above, Grey takes a doctrine of the dominant culture and inserts it into the speech of a representative of Indigenous peoples.

A more famous and possibly more consequential example of literary voice appropriation is Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851). Published ten years before the United States entered its horrific civil war, the novel’s primary importance is that it portrayed Southern life and customs. It concentrated on the institution of slavery in Kentucky and Louisiana. A number of the key plot ideas in the book are content appropriation from stories she heard while living in Cincinnati, and some characters and situations are derived from the voice appropriation of the popular minstrel shows of the time. (See Chapter 4, Section 4.7.) Because Stowe wrote about the South but never lived there, many things presented in the story can be classified as voice appropriation. For example, here is a passage from Chapter 30 (“The Slave Warehouse”). It includes speculation about the motivations of specific behaviors.

Excerpt from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin

A slave warehouse! Perhaps some of my readers conjure up horrible visions of such a place. They fancy some foul, obscure den, … But no, innocent friend; in these days men have learned the art of sinning expertly and genteelly, so as not to shock the eyes and senses of respectable society. Human property is high in the market; and is, therefore, well fed, well cleaned, tended, and looked after, that it may come to sale sleek, and strong, and shining. A slave-warehouse in New Orleans is a house externally not much unlike many others, kept with neatness; and where every day you may see arranged, under a sort of shed along the outside, rows of men and women, who stand there as a sign of the property sold within. …

The dealers in the human article make scrupulous and systematic efforts to promote noisy mirth among them, as a means of drowning reflection, and rendering them insensible to their condition. The whole object of the training to which the [Black man] is put, from the time he is sold in the northern market till he arrives south, is systematically directed towards making him callous, unthinking, and brutal. The slave-dealer collects his gang in Virginia or Kentucky, and drives them to some convenient, healthy place,—often a watering place,—to be fattened. Here they are fed full daily; and, because some incline to pine, a fiddle is kept commonly going among them, and they are made to dance daily; and he who refuses to be merry—in whose soul thoughts of wife, or child, or home, are too strong for him to be gay—is marked as sullen and dangerous, and subjected to all the evils which the ill will of an utterly irresponsible and hardened man can inflict upon him. (Stowe 1852, p. 155)

Although the book is a work of fiction, Stowe, like Grey, represents a real place and its culture, and does so with a political purpose. The second quoted paragraph includes voice appropriation. However, it is not as explicit or obvious as Grey’s presentation of Nophaie as a racial spokesperson. Although no speech or dialogue occurs here, Stowe goes beyond descriptions of what can be seen and heard. She says that the enslaved men were encouraged to make music. Some danced. Others did not. This sets up her presentation of the thinking and intentions of both the Southern slavers and the enslaved men. Because “some incline to pine” for home and family, the slavers encouraged them to engage in practices that might redirect their thoughts and attitudes. By implication, those who make “merry” with the music are not pining, or at least not as much, implying that some of the enslaved men accept their abusive treatment and status as property. While it is done in a less obvious way than Grey’s “The Vanishing Race,” Stowe practices voice appropriation. (For another example, see Chapter 4, Section 4.8).

Voice appropriation should never be accepted at face value. Stowe is writing about the interactions of two groups with distinct cultures, but she is an “outsider” to both of them. Her understanding of African-derived culture, especially music, was likely based on the craze for minstrel performances and “Ethiopian” songs (Meer 2005, pp. 9-11). But that form of music and dance was a grotesque White parody of Black culture.

Consider an alternative reading of the “noisy mirth” Stowe interprets for us. Music and dance are central to the spiritual life of the African societies brutalized by the transatlantic slave trade. In the United States, many Black communities retained their ancestral rituals of religious dancing. Therefore, the music and dancing described by Stowe might be a continuation of those practices and not, as she implies, mere entertainment. To an outsider, it looks like making “merry” (having fun). However, what Stowe describes might instead be a form of defiance through cultural affirmation. (See figure 1.17.) It might be prayer for deliverance rather than frivolous diversion. In other words, Stowe’s interpretation might be a serious misrepresentation based on her own Puritan-derived perspective on music and dance, which she projects into another culture. We know from many 19th-century written records that White outsiders routinely saw African-based communal religious dance as mere entertainment. In fact, Uncle Tom’s Cabin directly mentions Timothy Flint ‘s travel book Recollections of the Last Ten Years (Stowe, chapter 15). Flint’s book claimed that the communal religious music and dancing in Place Congo, New Orleans, was “license and revelry” demonstrating “forgetfulness of the past” (Flint 1826, p. 140). Basically, Flint witnessed a religious practice and thought he was looking at a party. He witnessed a preservation of ancestral memory and saw “forgetfulness.” Given that Stowe goes out of her way to call attention to Flint’s book, it is likely that she was relying on that source and repeating the same mistake.

1.8. Overlapping Appropriations

The examples of the last two sections have been presented as illustrating distinct types of cultural appropriation. However, the four types of non-tangible appropriation are frequently combined in practice. Look again at the example of van Gogh’s copy of a Hiroshige print (figure 1.11. ). The painting gives us three types of non-tangible cultural appropriation, and perhaps it gives us all four.

Content appropriation: van Gogh directly copies Hiroshige’s content, a flowering plum tree in a public garden.

Style appropriation: By copying Hiroshige’s print, van Gogh appropriates aspects of Hiroshige’s personal style. Some aspects of this style were highly innovative, especially his fondness for placing one object so close to the viewer that it fills most of the picture. In many of Hiroshige’s later prints, the featured object is pictured as being so close to the viewer that parts of it fall outside the picture frame. Other elements of the scene are then placed at a distance and therefore appear very small.

Motif appropriation: By directly copying the print, van Gogh picks up the Japanese design principle of placing multiple text boxes within the picture frame. This feature is specific to woodblock prints of this era. It is not a design feature of other Japanese visual art. These boxes were often given a customized design that was unique to just that one print series. Ironically, van Gogh’s version eliminates a distinctive Hiroshige motif. The original displays Hiroshige’s “signature” design of indentations at the four corners of the print’s border.

Voice appropriation: van Gogh may have selected this image because there is a spiritual dimension in the cultural tradition of viewing plum blossoms in the early spring. At this point in his life, van Gogh was beginning to identify himself as a Buddhist. He was probably aware that this image reflects an East Asian, Buddhist perspective on nature that was uncommon in Europe in the late 19th century. Therefore, van Gogh may have appropriated this content because it celebrates the tradition of blossom-viewing, which expresses a particular spiritual and philosophical relationship to nature and seasonal change. In this way, the image “voices” or expresses an East Asian or specifically Buddhist philosophy of nature that was only gradually becoming understood in Europe and European-derived societies.

As this example illustrates, content and voice appropriation are often intertwined. A contemporary example is the combination of voice and content appropriation that doomed La Chingona Cannabis.

Contemporary Voice and Content Appropriation: La Chingona Cannabis

La Chingona Cannabis was a growing business in California until their voice appropriation was discovered. Launched in 2020, the name is slang for “Bad Ass Woman” and the company advertised itself as owned and operated by the three Del Rosario sisters from Guadalajara, Mexico. Advertising and packaging featured women dressed to celebrate the Mexican holiday Dia De Los Muertos (Day of the Dead). (See figure 1.18.)

However, the Del Rosario sisters were a fiction created for marketing purposes. Hispanic women in Los Angeles were angered to learn that the company was actually founded by an American man with one Mexican grandparent, who appropriated stories about three sisters in Guadalajara from his rommmate at Harvard Business School. The other co-owners of the company were non-Hispanic men. This discovery quickly resulted in a social media campaign against the company’s voice appropriation, and the resulting boycott led to removal of the La Chingona brand from the cannabis market. In the face of the negative backlash, the brand existed for less than a year (Pineda 2020).

For another example of complex, overlapping appropriations, consider Giacomo Puccini’s opera La Bohème, which premiered in 1896. It adapted parts of Henri Murger’s 1851 novel, Scènes de la vie de bohème. Puccini, an Italian composer, appropriated a story set in Paris, France, and so the opera ends up portraying Parisian social life as it was some sixty years before the opera was written. Famously, the book and opera portray the distinctive “Bohemian” lifestyle, social interactions, and values of an artistic subculture that emerged in Paris in the early 19th century. As a result, voice appropriation follows from the high degree of content appropriation. Furthermore, since Puccini was not part of this subculture, this voice appropriation is a case of cultural appropriation.

However, some might object that La Bohème is not cultural appropriation, because one European artist is appropriating from another European artist in the same century. They share the same culture, so Puccini is not an outsider in relation to the material he adapted. Although it is true that 19th-century France and Italy have some shared cultural history, it does not follow that Puccini was a cultural insider with respect to this material. Treating him as an insider rather than an outsider reflects an extremely crude understanding of cultural unity. Recall the earlier example of two American poets, Emily Dickinson and Maya Angelou. Shared culture is often combined with cultural diversity. National differences are a major example. By any measure, Italy and France have very distinct cultures. Even there, national boundaries are only a crude approximation of major cultural differences. Most countries contain ethnic and religious diversity, leading to cultural distinctions between people who might live next door to one another. In fact, that point is central to the story of La Bohème, especially in Act II, in which different social classes mingle and the poor Bohemians scam Alcindoro, a wealthy aristocrat. So, La Bohème counts as cultural appropriation even if the source and the opera emerge from a “shared” broader culture. (See Chapter 2 for an explanation of how ethnicity relates to culture.)

Voice appropriation is undeniable in several of Puccini’s other operas, especially Madama Butterfly (1904). (See figure 1.19.) It has been and remains one of the most-performed operas in the world. Once again, voice appropriation is embedded in content appropriation. In this case, Puccini appropriates his basic content from a short story by American author John Luther Long, who seems to have appropriated the basic plot from the English translation of a recent French novel, Japan: Madame Chrysanthème (1887). The opera also has a second stream of content appropriation. It features identifiable Japanese and Chinese melodies, which are woven into Puccini’s own original music. As he did with La Bohème, Puccini keeps the original setting and time period. Pinkerton, an officer of the U.S. Navy, is stationed in Japan. He betrays and ruins Cio-Cio-San, the Japanese woman he uses as his “plaything” and then abandons. Later, he returns to Japan with his new American wife, Kate, and demands that Cio-Cio-san give up their child. He plans to return to the United States with the child, but not her. In a highly emotional final scene, Cio-Cio-San commits suicide.

Madam Butterfly: A Japanese Tragedy

Music by Giacomo Puccini

Italian libretto by L. Illica and G. Giacosa

English version by R. H. Elkin, 1906

Closing scene of the opera:

Kate [wife of Pinkerton]: Through no fault of my own, I am the cause of your trouble. Ah, forgive me pray.

Butterfly: … And how long ago is it he married you?

Kate:: A year. And will you let me do nothing for the child? I will tend him with most loving care. [Butterfly does not reply] ‘Tis hard for you, very hard, But take the step for [your child’s] welfare.

Butterfly: Who knows! All is over now!

Kate: Ah, can you not forgive me, Butterfly?

Butterfly: ‘Neath the blue vault of the sky there is no happier lady than you are. May you remain so,nor e’er be sadden’d through me. Yet it would please me much. That you should tell [Pinkerton] that peace will come to me. …

Kate: And can he have his son?

Butterfly: His son I will give him if he will come to fetch him. Climb this hill in half an hour from now.

[Everyone leaves and Butterfly is alone]

She takes a dagger, which, enclosed in a waxen case, is leaning against the wall near the image of Buddha. Butterfly piously kisses the blade, holding it by the point and the handle with both hands.

Butterfly [softly reading the words inscribed on it]: Death with honour is better than life with dishonour.

[She points the knife sideways at her throat. The door on the left opens, showing her maid’s arm pushing in the child towards his mother: he runs in with outstretched hands. Butterfly lets the dagger fall, darts toward the baby, and hugs and kisses him almost to suffocation]

Butterfly: You? you? you? you? you? you? you? … [Taking the child’s head in her hands, she draws it to her.] Though you ne’er must know it,`tis for you, my love, for you I’m dying. … That you may go away beyond the ocean, never to feel the torment when you are older, that your mother forsook you!

My son, sent to me from Heaven, straight from the throne of glory, take one last and careful look at your poor mother’s face! That its memory may linger, one last look! Farewell, beloved! Farewell, my dearest heart! Go, play, play.

[Butterfly takes the child, seats him on a stool with his face turned to the left, gives him the American flag and a doll and urges him to play with them, while she gently bandages his eyes. Then she seizes the dagger, and with her eyes still fixed on the child, goes behind the screen.

The knife is heard falling to the ground, and the large white veil disappears behind the screen.

Butterfly is seen emerging from behind the screen; tottering, she gropes her way towards the child. The large white veil is round her neck; smiling feebly, she greets the child with her hand and drags herself up to him. She has just enough strength left to embrace him, then falls to the ground beside him. … ]

Excerpt, ending of Madame Butterfly

John Luther Long

… As [Kate Pinkerton] advanced and saw Cho-Cho-San, she stopped in open admiration.

“How very charming — how lovely — you are, dear! Will you kiss me, you pretty — plaything!”

Cho-Cho-San stared at her with round eyes — as children do when afraid. Then her nostrils quivered and her lids slowly closed.

“No,” she said, very softly.

“Ah, well,” laughed the other, “I don’t blame you. They say you don’t do that sort of thing — to women, at any rate. I quite forgive our men for falling in love with you. Thanks for permitting me to interrupt you. And, Mr. Sharpless, will you get that [telegram] off at once? Good day!”

She went with the hurry in which she had come. …

They were quite silent after she was gone — the consul still at his desk, his head bowed impotently in his hands.

Cho-Cho-San rose presently, and staggered toward [the American consul]. She tried desperately to smile, but her lips were tightly drawn against her teeth. Searching unsteadily in her sleeve, she drew out a few small coins, and held them out to him. He curiously took them on his palm.

“They are his, all that is left of his beautiful moaney. I shall need no more. Give them to him …Thang him — that Mr. B.F. Pikkerton — also for his kineness he have been unto me. …”

[A short time later, at Cho-Cho-San’s home]

She sat quite still, and waited till night fell. Then she lighted the [lamp], and drew her toilet-glass toward her. She had a sword in her lap as she sat down. It was the one thing of her father’s which her relatives had permitted her to keep. It would have been very beautiful to a Japanese, to whom the sword is a soul. A golden dragon writhed about the superb scabbard. He had eyes of rubies, and held in his mouth a sphere of crystal which meant many mystical things to a Japanese. The guard was a coiled serpent of exquisite workmanship. The blade was tempered into vague shapes of beasts at the edge. It was signed, “Ikesada.” To her father it had been Honor. On the blade was this inscription:

To die with Honor

When one can no longer live with Honor.

… “To die with honor — ” She drew the blade affectionately across her palm. Then she made herself pretty with vermilion and powder and perfumes; and she prayed, humbly endeavoring at the last to make her peace. …

Then she placed the point of the weapon at that nearly nerveless spot in the neck known to every Japanese, and began to press it slowly inward. She could not help a little gasp at the first incision. But presently she could feel the blood finding its way down her neck. It divided on her shoulder, the larger stream going down her bosom. In a moment she could see it making its way daintily between her breasts. It began to congeal there. She pressed on the sword, and a fresh stream swiftly overran the other — redder, she thought. And then suddenly she could no longer see it. She drew the mirror closer. Her hand was heavy, and the mirror seemed far away. She knew that she must hasten. But even as she locked her fingers on the serpent of the guard, something within her cried out piteously. They had taught her how to die, but he had taught her how to live — nay, to make life sweet. Yet that was the reason she must die. Strange reason! She now first knew that it was sad to die. He had come, and substituted himself for everything; he had gone, and left her nothing — nothing but this.

The maid softly put the baby into the room. She pinched him, and he began to cry.

“Oh, pitiful Kwannon! Nothing?”

The sword fell dully to the floor. The stream between her breasts darkened and stopped. Her head drooped slowly forward. Her arms penitently outstretched themselves toward the shrine. She wept.

“Oh, pitiful Kwannon!” she prayed.

The baby crept cooing into her lap. The little maid came in and bound up the wound.

When [Kate] Pinkerton called next day at the little house on Higashi Hill it was quite empty.

Cio-Cio-San is a victim of racism in all versions of the story, which makes her a sympathetic character. At the same time, it presents “Asian women as submissive and exotic sex objects” (Hu 2019). In addition, there seems no good way to understand Cio-Cio-San’s surrender of her son and suicide at the end of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly other than to see her as the symbolic embodiment of an “Oriental” willingness to submit to “the West.” Some people defend the story and the opera on the grounds that its exposure of American racism gives it an “anticolonial perspective” (Groos 2023, p. xvii). By creating empathy for Cio-Cio-San, it is critical of exploitive “temporary marriages” of young women in Japanese port cities that were open to foreigners. That seems correct. However, it is also the case that Puccini’s version presents her as accepting her exploitation and tragic fate. This is a significant change from Long’s original story, in which Cho-Cho-San ultimately defies her American “husband” and gets the upper hand. However, Puccini appropriated his content from an alternative version, a stage play that ends with her suicide. (As content appropriation, the opera is therefore an appropriation from an appropriation of an appropriation!) Because Puccini used the version with Cio-Cio-San’s suicide instead of Long’s version and her defiant escape with the child, it is difficult to avoid concluding that this famous opera is a racist fantasy. It endorses a stereotype of Asian women as “meek and obedient [and] disposable sexual objects to be owned by men” (Wang 2021).

The message of Madama Butterfly is so offensive to many 21st-century viewers that the New Orleans Opera rewrote it for a 2023 production. In their new production, the opera has Long’s original ending.

Many years later, the content of La Bohème and Madama Butterfly reappeared in new forms. The two operas were the primary source material for a pair of popular musicals of the late twentieth century, Rent (1993) and Miss Saigon (1989). Jonathan Larson appropriated the content of La Bohème as Rent. He updated the story and setting to his own social surroundings, New York City in the 1990s, so Rent is an example of content appropriation but not necessarily voice appropriation. In contrast, the content appropriation that transformed Madama Butterfly into Miss Saigon is a case of further voice appropriation. Miss Saigon updates the setting to Viet Nam and Thailand in the 1970s, but once again the focus is a culture clash involving American military personnel in East Asia. The characters get new names, but the “love” story and tragic conclusion are basically the same. Like Madama Butterfly, Miss Saigon repeats and endorses colonial fantasies about a non-Western society, especially with respect to women.

Some people resist the idea that Puccini’s Butterfly and the derivative Miss Saigon are racist, pro-colonial fantasy. They are excused on the grounds that they are merely entertainment, or “just a story.” Or they are excused on the grounds that they are artworks, and so our response should focus on their universal themes concerning our shared humanity. Such responses are simplistic. They can be entertaining, and art, and pro-colonial fantasies all at the same time. A story or picture or song often means more than it literally says. Stories — especially stories that become popular or ones that are shared over several generations — almost always communicate core values and beliefs of the group that finds them entertaining or interesting. Cultural appropriation adds another layer of complexity to our communications. One layer may have a positive message while another layer conveys negative messages. Sadly, sometimes this allows racist messages to be packaged in the resulting mixture of entertaining content.