4 Constructing a Dominant Culture: The 1800s

Theodore Gracyk

Authorship

Sections 4.3 and 4.5 and the last two paragraphs of section 4.4 are edited, remixed, extensively rewritten and expanded by Theodore Gracyk, using material in Chapter 8 of American Encounters: art, history, and cultural identity, which is authored, remixed, and/or curated by Angela L Miller, Janet Catherine Berlo, Bryan J Wolf, and Jennifer L Roberts and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. All other material authored by Theodore Gracyk.

Chapter Goals

- Understand how the dominant culture promoted ideas about their racial identity

- Define the Romantic view of nature

- Define the sublime

- Define Manifest Destiny

- Understand how landscapes promoted ideas about American identity

- Understand how landscapes can imply racial themes

- Understand the legacy of minstrel shows

4.1 Two Visions of the United States

We are now entering the historical period in which the concept of race became a common way to think about group differences.

Almost every adult American knows that the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. Far fewer can name the year when the country actually became unified under a federal constitution: 1789. From 1781 until 1789, the country was governed under “articles of confederation” rather than the current system. Consequently, George Washington was not the first president of the country following the Revolution. He was the first president under the new government system, the one that is now in place.

Adoption of the constitution was a difficult process. One of the most interesting and important documents from this time period is the set of newspaper editorials written (anonymously) by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. These “Federalist papers” were a public relations push to get the state of New York to accept a stronger federal government. The most famous of these is number 10, in which Madison argued that only a strong federal government could protect the rights of individuals.

Madison addressed an unpleasant reality: many people had not supported the Revolution, and the nation was even less unified after independence was secured. The 13 states had competing interests, and it was already clear that North and South had distinct histories and had developed different cultures. In a society of “factions” and “clashing interests,” how can minority groups expect to avoid oppression? The answer, he proposed, was that the very lack of national unity would allow representative government to avoid the oppressive tendencies of populism. The various states would be distinct in their own laws and customs, but this very diversity should prevent any particular “prejudice” from being uniform or common enough to influence the national government.

For Madison, a dominant, uniform American culture was not desirable. It was dangerous. This view created an internal tension within the Federalist papers. In number 2, Jay had argued that American democracy would succeed because Americans are already united as “one united people—a people descended from the same ancestors, the same language, professing the same religion.” The myth of a unifying ancestry was already in place.

Superficially, Jay and Madison agreed that there was no need to seek consensus in a dominant culture. However, they gave opposing reasons: Jay thought we already had it in place. From the very start, therefore, there were two visions of the nation and its culture. On the one side (Jay), preservation of freedom for those of shared ancestry and language would be preserved by using the twin tools of exclusion and assimilation. On the other side (Madison), preservation of freedom would require an embrace of the greatest possible diversity.

This chapter will provide an overview of some ways in which a national identity was constructed in different art forms during the nation’s the first 100 years. The unifying theme was the idea that the United States was a land of “destiny” for “this American race” (United States Congress 1846, p. 159). By “this American race,” the dominant culture understood themselves as sharing an Anglo-Saxon ancestry and heritage. Although modern genetic testing shows that there was no identifiable ancestral unity among early colonialists (see chapter 2, section 2.2), the myth of a founding “race” continues to be cited with approval in American politics (Burnett 2021).

The various arts played a prominent role in endorsing the myth of the racial unity and superiority of the dominant culture. Both content and voice appropriation were common tools in this construction of national identity.

4.2 The National Anthem

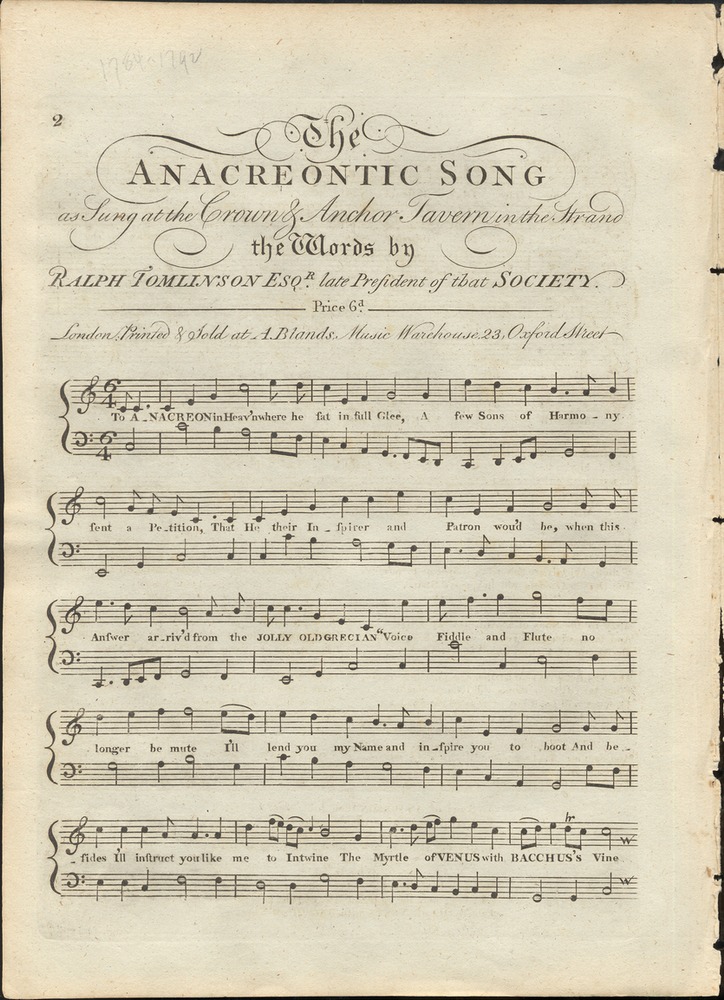

The United States did not adopt a national anthem until 1931, more than a hundred years after “The Star-Spangled Banner” was composed. The words were written as a set of verses by Francis Scott Key. The four verses describe Key’s experience watching the British bombing of Fort McHenry on September 13, 1814, as part of the ongoing War of 1812. However, Key did not write the music. He appropriated it wholesale. Key wrote his words to fit a well-known English song, “The Anacreontic Song,” by John Stafford Smith. (See figure 4.1.) Key had previously set a different set of words to the same music, with a lyric titled “When the Warrior Returns from the Battle Afar.” Titled “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” Key’s new poem was initially published on broadsides (oversize sheets printed on one side) distributed in the streets of Baltimore and at Fort McHenry. These sheets of lyrics show no music. They simply specify, “Tune—Anacreon in Heaven.”

The appropriation of the music of entire songs was a common practice in the 18th and 19th centuries. (This is to be understood as content appropriation.) A number of American popular songs were written this way. Part of the initial appeal of Key’s song was the fact that many people already knew the music.

Familiar as it may be, “The Star-Spangled Banner” contains several unfamiliar verses. The “land of the free” is not a call for liberty for all. It is, for Key, the land of “freemen” who rule over “the hireling and slave.” Key was a slave owner and, later, as district attorney for Washington, D.C., an enforcer of the slavery system. However, his personal history is complex. On the one hand, he recognized the cruelty of the slave trade and wanted to stop bringing any more enslaved people into the country. His family were became wealthy as slaveholders, yet he freed some of them and also provided legal advice to Black people who sought their freedom. On the other hand, after the War of 1812 he helped found the movement that promoted the mass deportation of all free Black people out of the U.S. (In Section 4.8, we will see that this position is also supported in the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.) Understood in relation to the politics of the time, the contrast between “freemen” and “slave” in the lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner” is to be understood as saying that Black people do not deserve to be free citizens in the United States. While Key saw that the country would be better without slavery, he also believed that the U.S. should be a “White” society, and he thought slavery should continue until the country set up a system to remove free Black people by deporting them to Africa.

The underlying racism of the song was well understood at the time it became the national anthem, which was one reason that it failed in multiple attempts to adopt it as the anthem. (For more discussion of the adoption of an anthem, see Chapter 6, Section 6.9.)

4.3 Nature’s Nation: The Hudson River School’s First Generation

The American poet Robert Frost once proclaimed, “The land was ours before we were the land’s … But we were England’s, still colonials.” Of English and Scottish ancestry, Frost gave voice to the perspective of the dominant group’s awareness that a long passage of time had been required before European colonizers and immigrants learned how to live with the American landscape. They had to unlearn an older Judeo-Christian notion of nature as a “howling wilderness” (Deut. XXXII. 10) and replace it with a more romanticized vision of the landscape as a realm of innocence and renewal. Although this new view of the land was promoted by American writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, the basic idea was appropriated from European Romantic thinkers. The Romantic view saw a deep connection between an ancestral people and their land. In the process of adapting these ideas to the American context, the dominant culture came to identify themselves (instead of Indigenous peoples) with the very nature they were hard at work conquering. According to one version of the dominant culture, the ideal was to replace the natural landscape with large-scale agriculture.

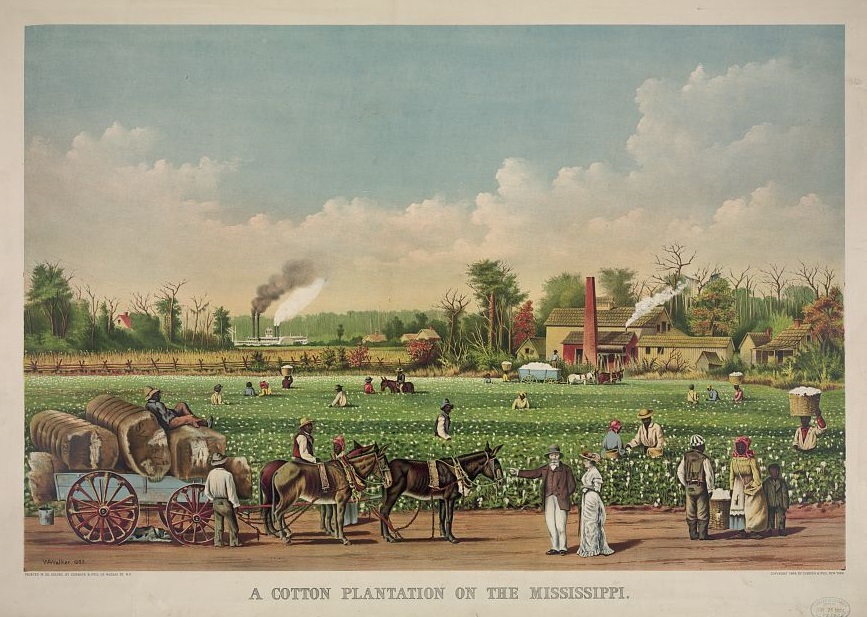

Nature was understood in many ways during the period from the Revolution to the Civil War. It was a pre-industrial realm separated from the stresses of modern life. It was a quasi-religious space filled with spiritual promise. But most of all — in keeping with the motivations of the colonizers — it was an untapped resource ripe for commercial development. (See figure 4.2., in which White landowners inspect Black laborers after the Civil War.) Ironically this meant that the dominant class saw nature much as they saw everyone else: as something to control, tame, and exploit. In the two decades prior to the start of the Civil War in 1861, the landscape was seen increasingly in national terms, which helped unite an increasingly divided nation by providing it with an image — or at least a dream — of shared values.

Unless one examines the underlying values that inform 19th-century images, this scene of Black labor on a Mississippi cotton plantation appears to be very different from Thomas Cole’s View from Mount Holyoke of 1836. (See figure 4.3.) However, we can think of the mass-produced print as the idealized goal and Cole’s oil painting as a representation of progress toward that goal.

Cole was a founder of a new approach to American landscape. He and his imitators are known as the Hudson River School of painting. However, Cole did not originate some of the techniques that characterize the Hudson River School. He had studied painting in Europe for three years. Returning to the United States, he designed a series of paintings that self-consciously appropriated and adapted the European revolution in landscape painting that he encountered in his European travels. He now looked for ways to translate the modern European treatment of landscape into a vehicle for American issues and values. Consequently, the first important period of American landscape painting was based on style and content appropriation.

View from Mount Holyoke shows that Cole was influenced by two distinct categories of landscape: the picturesque and the sublime. As the name suggests, the picturesque was a pretty rural scene. By focusing on the right side of Cole’s picture of a bend in the Connecticut River in western Massachusetts, one sees a picturesque scene. Nature is presented as a pleasant or delightful place. In contrast, the sublime is a category of representation that aims to instill awe — even fear — in the audience. The key ingredients are some combination of vast scale, wildness, and powerful, threatening forces. In Europe, the Swiss Alps were frequently presented as the model of sublimity of nature. Generally, Romanticism understood the sublime as valuable for revealing supernatural forces at work in nature. In Cole’s painting, the sublime dominates the left half.

The irony is that the “American sublime” pioneered by Cole and others of the Hudson Valley school did not really originate in America. As with so much art, Cole’s work involves significant appropriation. Most notably, he borrows from the work of an English painter, J. M. W. Turner. In the early part of the 1800s, Turner created a series of innovative landscape paintings emphasizing a dramatic interaction of light and color. Turner’s revolutionary style features bold, sweeping brushstrokes, vivid colors, and atmospheric effects that combine to create highly expressive moods. The effect is to portray nature itself as an emotionally charged, dramatic participant in events. Some of Turner’s most powerful images are pictures of storms at sea. These would prove to be among the most influential landscapes ever created. Turner made many watercolor studies while directly observing violent weather, and no previous painter had ever captured storm clouds with such accuracy and power. (See figure 4.4.) More generally, the Hudson River School artists studied and copied Turner’s approach to the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. They often used the same golden, atmospheric light that Turner employed in his paintings.

One of Turner’s most famous paintings is Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812). Cole visited England in 1829 and studied a number of Turner storm scenes, including Snow Storm. (Unfortunately, that painting cannot be shared in open access publications.) If Turner’s Snow Storm is flipped, moving the storm clouds from left to right, the result looks very much like Cole’s View from Mount Holyoke. The left, darker half of Cole’s landscape shows a Turner-derived thunderstorm passing from the area, creating one of the first great representations of the sublime in American art.

Looking more closely at Cole’s landscape, a series of details reveals that it is not offered simply to provide an objective look at an American landscape on a late summer’s afternoon. Choices have been made to convey a set of ideas that would have appealed to the dominant class and, therefore, to potential buyers of this painting. The painting famously brings together precisely those aspects that Cole recommended as “American scenes.” Above all, it reflects the key idea that he advance in his “Essay on American Scenery,” which is that “the most distinctive, and perhaps the most impressive, characteristic of American scenery is its wilderness.”

Excerpt from Thomas Cole, “Essay on American Scenery” (1836)

American associations are not so much of the past as of the present and the future. Seated on a pleasant knoll, look down into the bosom of that secluded valley [where] a silver stream winds lingeringly along … glancing in the sunshine: on its banks are rural dwellings shaded by elms and garlanded by flowers — … freedom’s offspring — peace, security, and happiness, dwell there, the spirits of the scene. On the margin of that gentle river the village girls may ramble unmolested — and … those neat dwellings, unpretending to magnificence, are the abodes of plenty, virtue, and refinement. And in looking over the yet uncultivated scene, the mind’s eye may see far into futurity. Where the wolf roams, the plough shall glisten; on the gray crag shall rise temple and tower — mighty deeds shall be done in the now pathless wilderness; and poets yet unborn shall sanctify the soil.

In View from Mount Holyoke, the sublime (and threatening) “pathless wilderness” is on the left. On the right, across the river, Cole includes smoke from the chimneys on various farmsteads. Haystacks are symmetrically arranged in the fields. Because it is a new country, Cole says, the American landscape is a work in progress. Refinement will gradually replace the “pathless wilderness,” and generations to come (not those who went before), “shall sanctify” it. His references to peace and the security of the village girls are, implicitly, a nod to the historical and recent past. In this part of the United States, the ongoing warfare between immigrants and Indigenous people has finally ended, shifting the American frontier farther west. A blasted tree trunk, a common symbol of nature’s power, shows the need to create houses for shelter. The American forest is a place of “danger and fear” (Zygmont 2015). Roads must be cut through the wilderness. In the middle background, swaths of forest are clear-cut by logging. The implication is that the same will happen with the woods of the hill from which we view the river. (Look closely at the center bottom: Cole has placed himself on this hill, sketching this valley. Landscape artists of this era traveled and sketched in the summer when the weather was good, and then returned each winter to their studios in cities to compose oil paintings based upon their earlier sketches.)

Cole is not picturing the frontier, the area where settlers pushing west came into direct conflict with Indigenous peoples. The area of the Connecticut River Valley pictured here was settled 40 years after the founding of the Massachusetts colony. Yet the idea of the frontier is part of the content of this landscape.

Physically and economically, the large cotton plantations of Mississippi were organized differently from the small farms of New England. North and South developed distinct cultures, fueling increasing political division. However, in both cases the economy was organized around agriculture. When Cole painted this scene, the United States was only just taking the first steps into the industrial revolution of factory and machine production. View from Mount Holyoke shows that the development of the Connecticut River Valley was well advanced. The American frontier had now shifted west to the Ohio Valley and just beyond. In the South, the cotton plantation represented the height of social and economic development. The Southern “cotton belt” had only recently arrived in Mississippi when Cole created this painting. Yet settlers were already pushing the plantation system (and slavery) westward into present-day Texas. The American insurrection that led to Texas independence happened the same year that Cole’s painting was created. (See more on that topic below, in Section 4.6.)

As each new set of states gained enough settler population to enter the union, the “wilderness” and the frontier shifted further west. Cole’s division of the landscape into two realms — with uncut forest on the left, or west — signifies the division of the continent into two, as well: a region of wildness, energy, and power (the region of the wild forest, and the storm) is just beyond a space of rational organization and control (the far side of the river, the East). The issue here is not nature, but the ability of settlers to harness and contain nature’s forces. The images of the Hudson River School promoted “the discovery, exploration and settlement of wilderness land” (Glueck 2006, p. B27). Nature must be transformed and tamed by culture.

4.4. Nature’s Nation: The Hudson River School’s Second Generation

The Hudson River School that Cole founded continued well into the 19th century and two dozen artists are associated with its style and ideals. However, as settlers moved west, so did its subject matter, shifting from the Northeast to the Rocky Mountains. The paintings and prints of Thomas Moran are a good example. Like Cole, Moran studied the work of Turner, first in reproductions and then during a trip to London when he spent several months making copies of Turner’s oil paintings and watercolors. As a result, Moran’s most successful works also appropriate from Turner’s landscapes. Beginning in 1871, Moran made a number of journeys through the American West, sketching on site and then producing huge oil paintings in his studio. Once he had achieved fame and wealth, he traveled to Europe again in order to paint some of the places featured in Turner’s work. Moran once summarized the most important lesson he learned from Turner: “Literally speaking, his landscapes are false; but they contain his impressions of Nature, and … convey that impression to others” (quoted in Anderson 1992, p. 16). Likewise, Moran explained, his own paintings were never intended to be accurate representations of what he painted: “I place no value upon literal transcripts from Nature. My general scope is not realistic; all my tendencies are toward idealization” (quoted in Anderson 1992, p. 16).

Chasm of the Colorado is typical of Moran’s treatment of the West. (See figure 4.5.) A storm, influenced by Turner, creates drama by dividing the painting into contrasting halves. The vast scale and the power of the storm combine to showcase awe-inspiring sublimity. Although less prominent than the one in Cole’s painting, Moran includes a few blasted, bare tree trunks in the lower left. There are absolutely no signs of human presence, falsely suggesting that Moran and his generation were the first people to ever see this area. (Contrast this technique with Albert Bierstadt’s treatment of the Rocky Mountains in Chapter 5, figure 5.14.) Many of his dramatic images of Yellowstone and the Rocky Mountains were then mass produced as lithographic prints, spreading his images to audiences who could not see the paintings in person. As a result, Moran’s vision of the American sublime shaped the public’s view of the American West. While he was president, Barack Obama had one of Moran’s smaller paintings on display in the Oval Office.

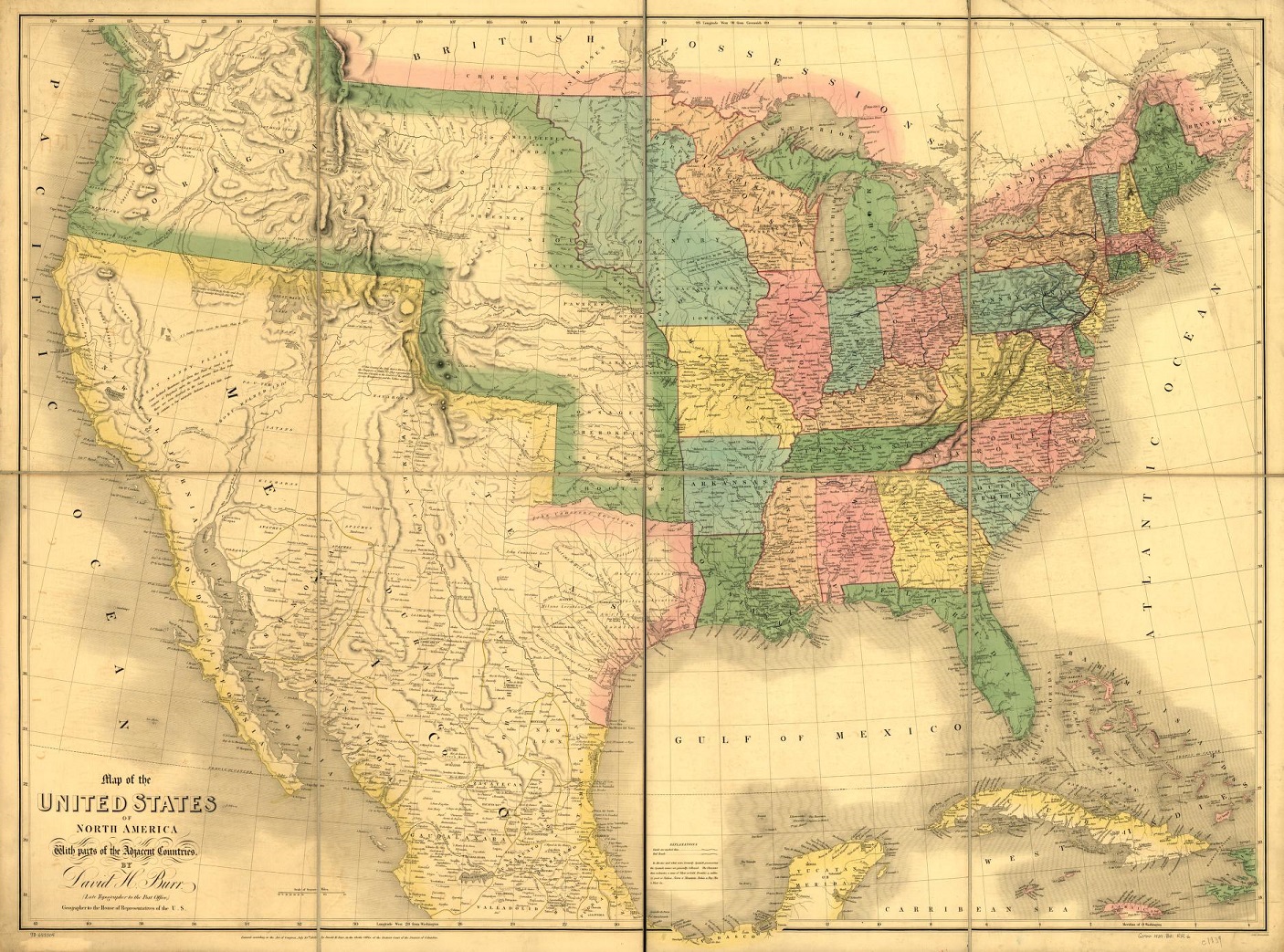

Moran’s audience understood his work through the lens of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. The phrase was popularized by journalist John Lewis O’Sullivan in editorials calling for “Anglo-Saxon emigration” beyond Texas (O’Sullivan 1845). The immediate issue was the annexation of Texas and the 1845 dispute with Great Britain about the location of the American-Canadian border in the Pacific Northwest. (See figure 4.6.) However, these short-term political issues encouraged Americans to think in bigger terms. O’Sullivan called for American settlers to seize any land they wanted and “overspread the continent allotted by Providence” (O’Sullivan 1845). In another publication, he proclaimed that it “is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the Continent which Providence has given for the development of the great experiment of liberty” (quoted in Hughes 2018, pp. 143-44). These ideas informed American political discourse and art for the remainder of the century. Manifest destiny was a nationalistic doctrine supporting massive land appropriation.

The symbolic message of paintings like Moran’s Chasm of the Colorado was twofold. First, the emphasis on sublimity conveyed the message that the West was a special place, alive with God’s power and majesty. Paintings such as this confirmed the idea that the West was “God’s country.” Second, it was undeveloped, unspoiled, and uninhabited. (Or, if inhabited, not the property of Indigenous peoples, because they had failed to develop the land.) Therefore, the dominant European, Christian culture had a right to possess and settle this new frontier. This reading of Moran’s work is not speculation. He was clear about what he wanted to show with his paintings of the West: “we possess a land of beauty and grandeur with which no other can compare” (quoted in Murphy 1912, p. 136).

For both 19th-century and modern viewers, these themes come together most clearly in Moran’s multiple versions of the Mountain of the Holy Cross. (See figure 4.7.) Here, the artist “directly invokes the role of the Christian God in creating the resplendent American landscape” (Bratton, p. vii). The mountain is located in Colorado, and snow in ravines gives the appearance of a cross after other snow has melted away. Moran first sketched the scene in 1871, and sold multiple paintings and print designs featuring the mountain. It is estimated that several million people saw Moran’s oil painting of it at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Viewers, most of them members of the dominant culture, saw it “as a powerful symbol of both religious and nationalistic significance” (Wilkins 1998, p. 143).

Paintings by Cole and Moran show how 19th-century American art approached the landscape symbolically. It was never simply documentation. European Romanticism was culturally appropriated to justify land appropriation. Artists were less interested in accuracy than in appeal to the wealthier class that supported the expense of oil painting and other fine art. The strongest appeal of any landscape was its function as a staging ground for American society as they envisioned it. The artist transforms nature into a place where social, cultural, and political concerns can be worked through symbolically.

4.5. Colonial Nostalgia in Popular Art

The symbolic endorsement of westward migration was one of two themes that unified the dominant culture. The second ingredient crucial to the nationalization of the landscape is the conversion of local places and events into sites of collective importance. As sectional differences intensified in the decades before the Civil War, artists, writers, and intellectuals attempted to imagine a version of the landscape untouched by regional tensions. They sought to achieve in their art what they could not experience in their lives: a feeling of national unity. The more polarized the nation became — the more torn by divisions of city and country, Black and White, wage earner and capitalist, North and South — the more pressure these artists experienced to heal the national mood. They did so by turning to local scenes and injecting them with shared national values.

Until it was replaced by visions of the West, New England in particular came to embody the spirit of the nation as a whole. (Cole’s river scene is in New England.) In fact, the region was not very representative of American values. Its leaders tended to be Whigs and dissenters from the national consensus. It staunchly opposed the Mexican War of 1846-48, seeing it as a barely disguised land grab by the South and West, an unwarranted opportunity to extend slavery westward. New Englanders tended to be better educated than the rest of the nation. The countryside was increasingly filled with factories and other developments of the industrial age to come. The woodlands were being cut down in order to provide fuel for the rapidly expanding railroads. After two centuries of bad agricultural practice, its farms were undergoing a decline as tillable land grew scarce and the soil became exhausted. Even its central ports, cities such as Boston, Providence, and New Haven, were all losing ground to New York, which by mid-century reigned supreme as the nation’s commercial capital.

What New England possessed that the rest of the nation lacked was a rich civic mythology. Artists and writers increasingly came to associate New England’s Puritan past with a history of civil and religious freedom. They defined the region’s revolutionary tradition — the battles of Lexington and Concord, the Boston Tea Party, the saga of Paul Revere — as embodiments of a national spirit. They converted New England from a modernizing industrial center to a spiritual standard-bearer for the nation. As it became less traditional, it was treated as more traditional. Images of New England scenery combined with poems like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” to celebrate a national history viewed through local New England eyes. Artists and writers converted the region from an increasingly marginalized area to the embodiment of national — or at least Northern — values.

At the same time that Thomas Cole and his imitators were mythologizing the Northeast in landscape, popular printmakers were marketing images of American scenes for those who could not afford an original oil painting. In Home to Thanksgiving, for example, George Henry Durrie (1820-63) created a fond reminder of agrarian values and “the good old days” (See figure 4.8). Thanksgiving was not yet an official American holiday, but it had become increasingly important. For example, it was the subject of a popular poem by John Greenleaf Whittier, “The Pumpkin” (1846). The pumpkin, of course, was one of the oldest of domesticated crops and native to the Americas. It was a staple part of the Indigenous food culture of North America. The poem is, therefore, also a celebration of appropriation from New England’s indigenous peoples.

Here is a sample verse.

Excerpt from John Greenleaf Whittier, “The Pumpkin”

Ah! on Thanksgiving day, when from East and from West,

From North and from South comes the pilgrim and guest;

When the gray-haired New Englander sees round his board

The old broken links of affection restored,

When the care-wearied man seeks his mother once more,

And the worn matron smiles where the girl smiled before,

What moistens the lip and what brightens the eye?

What calls back the past, like the rich Pumpkin pie?

Durrie’s image illustrates the poem’s sentiments. It links the New England countryside not only to the Pilgrim past (referenced by Whittier), but to the contemporary rituals of family togetherness. New Englanders had long campaigned to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. Led in part by the efforts of the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, they had some success when Abraham Lincoln (1809-65), at the height of the Civil War, proclaimed a national day of “thanksgiving” to be held annually on the last Thursday of each November. Like Whittier’s poem, the mass-produced print Home to Thanksgiving unites families and friends of different generations in a shared moment of renewal. The cold of the snow and sky is overcome by the tidy order of the New England farmstead. The animals are well tended, the buildings in good repair, and the wood supply abundant. The rectilinear composition — the use of horizontals and verticals to organize space — reinforces the viewer’s sense of order. The general air of serenity in Durrie’s landscape represents a larger national dream of harmony embodied in the self-sustaining New England farm. This is a popular version of Cole’s vision of “freedom’s offspring — peace, security, and happiness.” Excluded were the other participants in the “first” Thanksgiving, the Indigenous people of New England.

4.6. American Expansion through Insurrection and Conquest

Looking back, it is difficult for 21st-century Americans to appreciate the central contribution of poets in the formation of American national identity. An important example is Walt Whitman. While many Americans felt excluded from Whittier’s New England vision of American values, appeals to freedom, self-reliance, and independence could still unite different regions and classes. (This ideology required a general consensus that Indigenous peoples and Black Americans did not and could not participate in those values.) Whitman’s poems were collected in his monumental book Leaves of Grass (1855), which was expanded with new poems five times during his lifetime. As much as any 19th-century American, Whitman promoted a vision of the United States as the world’s first true democracy (Folsom 1998).

An interesting example of Whitman’s patriotism is his poem about the execution of American “rangers” by Mexican troops in 1836, an event that took place a few weeks after the American defeat at the Alamo. These were two famous setbacks in the illegal insurrection against Mexico by Americans who sought new land for the slave-based plantation system. The Americans eventually won, leading to Texas independence and then statehood. However, the immediate context for Whitman’s composition of the poem was another, larger conflict: the Mexican-American war of 1846-48. The war was fought over several issues, including the question of how much land belonged to Texas when it achieved statehood in 1845. Coupled with the swift, less-bloody seizure of California in 1846, the outcome of the Mexican War was to establish undisputed political and racial dominance over all of the territory that became the contiguous 48 states.

This is the context in which Whitman looked back to the events of 1836. To compose the poem, he engaged in content appropriation from old newspaper articles, including an account by a Mexican military officer who was there. This eye-witness description was translated from Spanish and published in several American newspapers (Hudder 2012, pp. 70-71). Three lines of Whitman’s poem are direct appropriations from this eye-witness account. Here is the poem as it appears in the first edition of Leaves of Grass.

Section 34 of “Song of Myself” (1855) from Leaves of Grass

I tell not the fall of Alamo . . . . not one escaped to tell the fall of Alamo,

The hundred and fifty are dumb yet at Alamo.

Hear now the tale of a jetblack sunrise,

Hear of the murder in cold blood of four hundred and twelve young men.

Retreating they had formed in a hollow square with their baggage for breastworks,

Nine hundred lives out of the surrounding enemy’s nine times their number was the price they took in advance,

Their colonel was wounded and their ammunition gone,

They treated for an honorable capitulation, received writing and seal, gave up their arms, and marched back prisoners of war.

They were the glory of the race of rangers,

Matchless with a horse, a rifle, a song, a supper or a courtship,

Large, turbulent, brave, handsome, generous, proud and affectionate,

Bearded, sunburnt, dressed in the free costume of hunters,

Not a single one over thirty years of age.

The second Sunday morning they were brought out in squads and massacred . . . . it was beautiful early summer,

The work commenced about five o’clock and was over by eight.

None obeyed the command to kneel,

Some made a mad and helpless rush . . . . some stood stark and straight,

A few fell at once, shot in the temple or heart . . . . the living and dead lay together,

The maimed and mangled dug in the dirt . . . . the new–comers saw them there;

Some half–killed attempted to crawl away,

These were dispatched with bayonets or battered with the blunts of muskets;

A youth not seventeen years old seized his assassin till two more came to release him,

The three were all torn, and covered with the boy’s blood.

At eleven o’clock began the burning of the bodies;

And that is the tale of the murder of the four hundred and twelve young men,

And that was a jetblack sunrise.

The overall point of this segment of Leaves of Grass is to praise the heroism of the men who fought to expand the United States. It is not merely that they gave their lives to expand the country. Whitman suggests that they did so because they possessed by an instinctive desire for freedom: “dressed in the free costume of hunters … None obeyed the command to kneel.” (Whitman passes over the point, made by an American survivor, that few of the Americans spoke Spanish and so they did not understand the command to kneel.)

Overall, the poem is structured to contrast the “glory of the race of rangers” with the treachery of the Mexican officials. Whitman is building a case for the full-scale American invasion of Mexico that would result in seizure of the Southwest. While it is not his central focus, he clearly assigns racial differences to the opposing forces of freedom and oppression. In this way, the poem reflects the country’s increasing tendency in the antebellum era to inject racial issues into political divisions and conflict. In this case, it is interesting to see that this was a new development in Whitman’s view of the situation. The topic of race played no such role in Whitman’s earlier newspaper writing in support of war with Mexico, where he directly endorsed seizure of New Mexico, Arizona, and California. For example, he contributed the following editorial to The Brooklyn Eagle in June, 1846, endorsing the recent start of the Mexican-American war. It shows that Whitman used voice appropriation in both his newspaper writing and his poetry when justifying America’s wars with Mexico.

Walt Whitman editorial in The Brooklyn Eagle, 1846

It is affirmed, and with great probability, that in several of the departments of Mexico — the large, fertile, and beautiful one of Yucatan, in particular — there is a wide popular disposition to come under the wings of our eagle… Rumor states that a mission has been, or is to be, dispatched to the United States, with the probably [sic] object of treating for annexation or something like it.

Then there is California, in the way to which lovely tract lies Santa Fe; how long a time will elapse before they shine as two new stars in our mighty firmament?

Speculations of this sort may seem idle to some folks. So do they not, we are assured, to many who look deep into the future. Nor is it the much condemned lust of power and territory that makes the popular heart respond to the idea of these new acquisitions. Such greediness might very properly be the motive of widening a less liberal form of government, but such greediness is not ours. We pant to see our country and its rule far-reaching, only inasmuch as it will take off the shackles that prevent men the even chance of being happy and good — as most governments are now so constituted that the tendency is very much the other way. We have no ambition for the mere physical grandeur of this Republic. Such grandeur is idle and deceptive enough. Or at least it is only desirable as an aid to reach the truer good, the good of the whole body of the people.

Whitman’s newspaper editorial begins by claiming to know that many of the people of Mexico feel oppressed and wish to join the United States. The actual historical context is that Mexico had recently gained its independence from Spain. Mexicans did not need to have liberty secured for them by the United States. Whitman then shifts to an expression of the American perspective. He denies that greed for new land for settlers motivates Americans. Assuming that no country except the United States is a genuine democracy, he proposes that American expansion is justified because it removes the “shackles” of tyranny.

The story that Whitman tells is the same one that was used by the English who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony: the people who will give up their land want us to come. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.6.) They need us to come. They consent to become a subordinate group. As can be seen in the poem sampled here, Whitman was a master of voice appropriation. He enters into his identification with others in order to create sympathy and unite people across the lines that divide Americans. However, he also uses voice appropriation to justify America’s belief in a manifest destiny to expand westward, supporting new lines of division in the process. The phrase “manifest destiny” had been popularized by O’Sullivan only a few months before Whitman wrote his editorial. Whitman joined the growing chorus of support for O’Sullivan’s claim that the ends justifies the means: a bloody westward expansion was justified because it brought “liberty” to conquered peoples. A decade after the fact, Whitman looks back and mourns the American dead in his poem about the Texas uprising. In the context of Leaves of Grass, it is folded into Whitman’s larger story of praise for American democracy.

4.7. Minstrel Shows and Plantation Songs

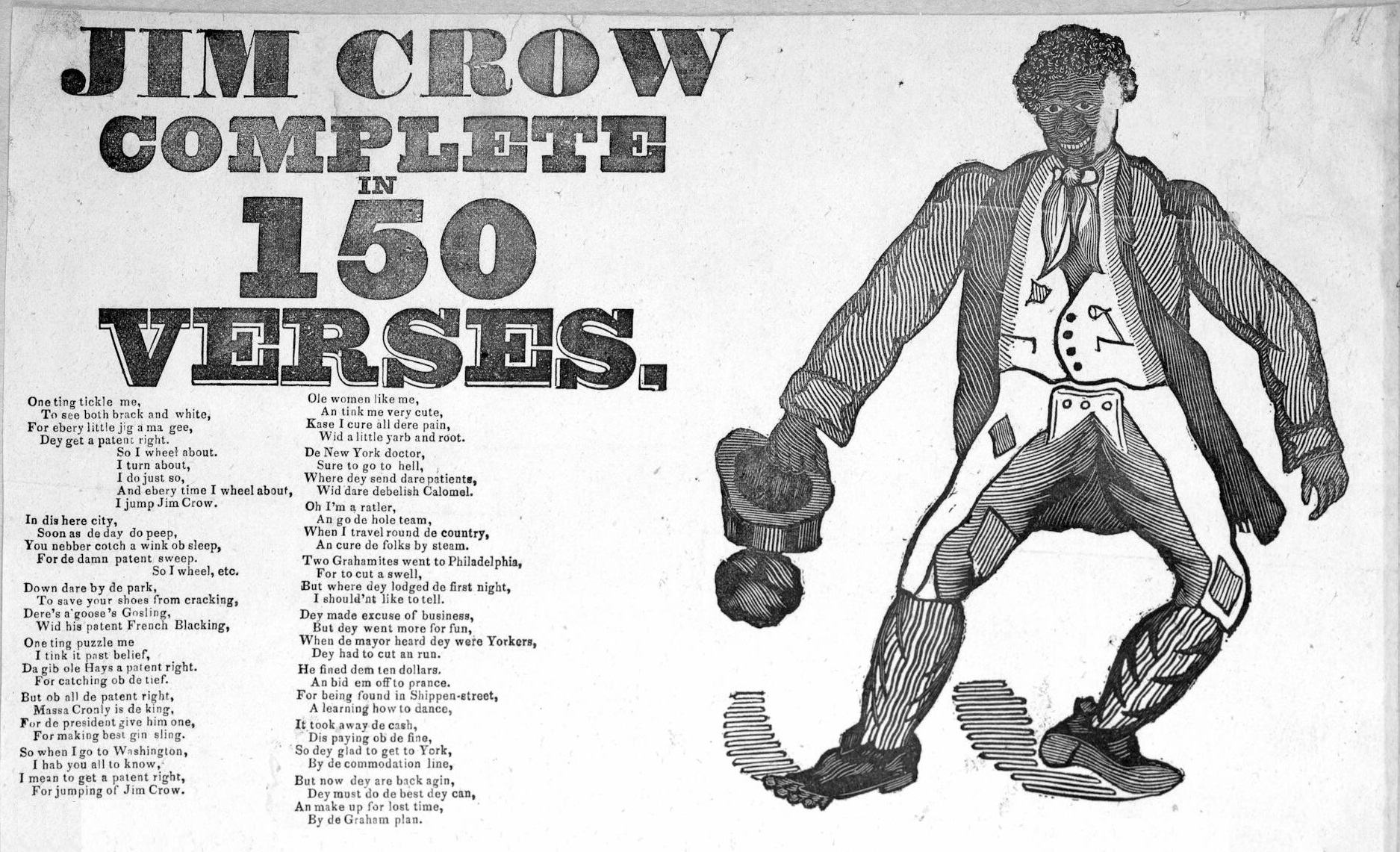

Abolitionist (anti-slavery) sentiment was strongest in New England. In the period when abolitionist views gained support, a new popular art form emerged that worked against their calls for reform. It was the minstrel show, and it is one of the most successful and most notorious traditions of content and voice appropriation in entertainment history. Beginning around 1828, increasing numbers of White entertainers dressed in rags, blackened their faces with burnt cork, and sang songs, danced, and told jokes that they claimed were authentic or genuine examples of Black culture. One-man performances soon developed into a stage tradition that presented a group of five or more “blackface” comedians and musicians and an evening’s performance of three acts.

The entertainment was delivered in dialect, that is, as an exaggerated stereotype of Black men talking. For example, the song “Old Folks at Home” (“Swanee River”) contains the line “There’s where my heart is turning ever, there’s where the old folks stay.” In the original sheet music, the words are given in dialect: “Dere’s wha my heart is turning ebber, dere’s wha de old folks stay.” This use of Black dialect is a classic example of voice appropriation, which extends to mimicking accents, copying slang or expressions, or adopting the tone and rhythm of speech associated with a particular group.

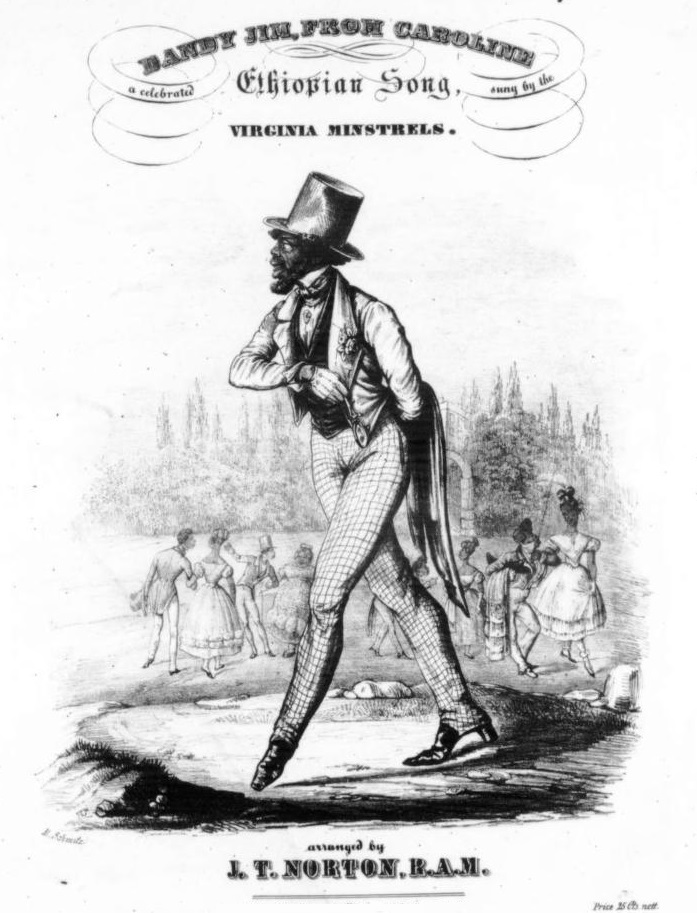

The first major minstrel star, Thomas Rice, claimed to have originated the minstrel character Jim Crow by borrowing the actual clothing of a Black dockworker in Pittsburgh, at that time a major port on the Ohio River with shipping routes into the American South. Rice popularized the song “Jump Jim Crow” together with an associated dance and shabby costume, but soon there was an entire industry of minstrel music. (See figure 4.9.) Many of these songs, such as “I Wish I Was in Dixie,” “Turkey in the Straw,” and “The Arkansas Traveler,” remain well known even today. Blackface minstrelsy was popular for so long that one such performance appears in the first full-length “talkie” (film produced with a synchronized soundtrack). The film, The Jazz Singer (1927) includes Al Jolson’s blackface performance of “My Mammy.”

Music scholar Greil Marcus summarizes the minstrel tradition in no uncertain terms: “white men stole the songs, speech, and gestures of American slaves or free African Americans, [and] they profited from turning black people into infantilized monsters of stupidity” (Marcus, in Lott 2013, p. xi). However, the enslavement of Black people had been a fact of American life since the early 17th century. So why was there a sudden explosion of stereotyping through minstrelsy? Eric Lott raised this question and reawakened interest in the history of the minstrel tradition. He proposed that it was due to changes in working-class life that were taking place in the 1830s and then, especially, in the 1840s (Lott 2013).

In American cities, recent Irish immigrants were the largest and most enthusiastic audience for minstrel entertainment. Although German immigrants were also a sizeable portion of laborers in Northern cities, Germans were regarded as racially aligned with the existing White population. The Irish were not. England had conquered Ireland and then appropriated most of the land, creating widespread poverty and encouraging Irish immigration to the United States. In the process, the English insisted that the Irish were not “White,” but a distinct, inferior race, and the men were generally characterized as lazy, stupid, violent alcoholics. American culture inherited these stereotypes from the English, and the growing Irish population was unwelcome, untrusted, and oppressed. As under-educated laborers, Irish immigrants saw free Black men as a threat to Irish employment. Consequently, many Irish immigrants supported slavery (which kept Black labor in the South) and adopted American racial prejudices. Minstrel shows were populist entertainment, but they were also quasi-political events in which working class men confirmed their relatively superior status in the American class system (Lott 2013, pp. 94-99). For example, the joke “Why did the chicken cross the road?” comes from minstrel shows, one of many that stereotyped Black characters as lacking intelligence (Taylor and Austen 2012, p. 5). There are, of course, other reasons for their popularity, but the voice appropriations of minstrel entertainment did a great deal to both create and solidify negative stereotypes of Black men. The first famous minstrel song, “Jump Jim Crow,” gave a name to the Jim Crow era of Southern segregation and disenfranchisement laws that lasted into the 1950s.

In the same way that White people are called “Caucasians,” after a region in south-eastern Europe, 19th century racial categories lumped all people of sub-Saharan Africa together as “Ethiopians.” In social settings where racial slurs were considered bad manners, minstrel songs were referred to as Ethiopian songs or melodies. (See figure 4.10) When their subject matter was Southern slave life, they were often referred to as “plantation songs.” They were, however, written by White composers, many of whom had never seen a plantation. One of the lingering effects of this voice appropriation was that it created a nostalgic, falsified history of the South. It created the impression that the slave-based plantation culture was basic to Southern identity. In reality, the rapid spread of the slave-based cotton industry coincided with the appearance and development of minstrel entertainment.

Before the Indian Removal Act of 1830 opened up cheap land in Alabama and the Mississippi Delta, cotton production was mostly limited to South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida (Beckert 2014, p. 103). Tobacco, not cotton, was the cash crop of the South. The westward spread of the cotton plantations was made possible by the defeat of a confederation of Indigenous peoples — primarily the Muskogee Nation — in the Creek War (1813-14). Led by the future president, Andrew Jackson, American forces defeated the Creek confederacy by finding allies among rival tribes. Afterwards, Jackson and the Americans betrayed their Indigenous allies by treating them as equivalent to the defeated tribes. With the Indian Removal Act and other actions that followed, the United States stripped land rights from all Indigenous peoples in the South, and most of the Indigenous population was forcibly removed to land west of the rich soil of the Mississippi floodplain. White slave-owners moved into Creek and Cherokee land. In a mere ten years, this appropriation of Indigenous land created the widespread and highly profitable “cotton economy” that has come to be associated with the antebellum South (Cozzens 2023, pp. 353-56).

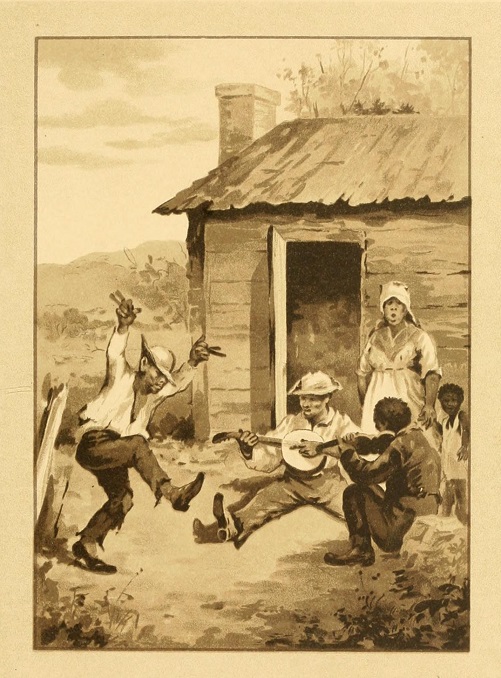

Minstrel entertainment played an important role in creating the general impression that the plantation system was both common and traditional. A classic example is the plantation song “Old Folks at Home” (“Swanee River”). It was written by Stephen Foster in 1851 for use in minstrel shows. (See figure 4.11.) It would have been sung by a blackface White man, pretending to be an enslaved Black man who is nostalgic for his mother and brother and the little “hut” of his childhood: “When shall I hear the banjo strumming/Down in my good old home?” (The choice of the Swanee River as the plantation’s location was completely random: it was chosen because it fit the meter and melody.) Foster’s personal goal with this voice appropriation was to humanize enslaved Black people. However, this song had the unintended effect of telling Northern audiences that the plantation system was long-standing and, seemingly, a happy life for the enslaved Black population. And because Foster’s song became so popular, other songwriters created a flood of similar plantation songs.

New England promoted nostalgia for the Pilgrims, pumpkin pie, and going home to mother. The minstrel shows promoted nostalgia for the institution of slavery in the South. In an interesting twist, plantation songs with themes of mother and homesickness had a special appeal for Irish immigrants (Lott 2013, 198). Parallel with the popularization of Thanksgiving, plantation songs promoted nostalgia for a way of life. Ironically, that way of life that had only recently spread to Southern lands appropriated from Indigenous peoples.

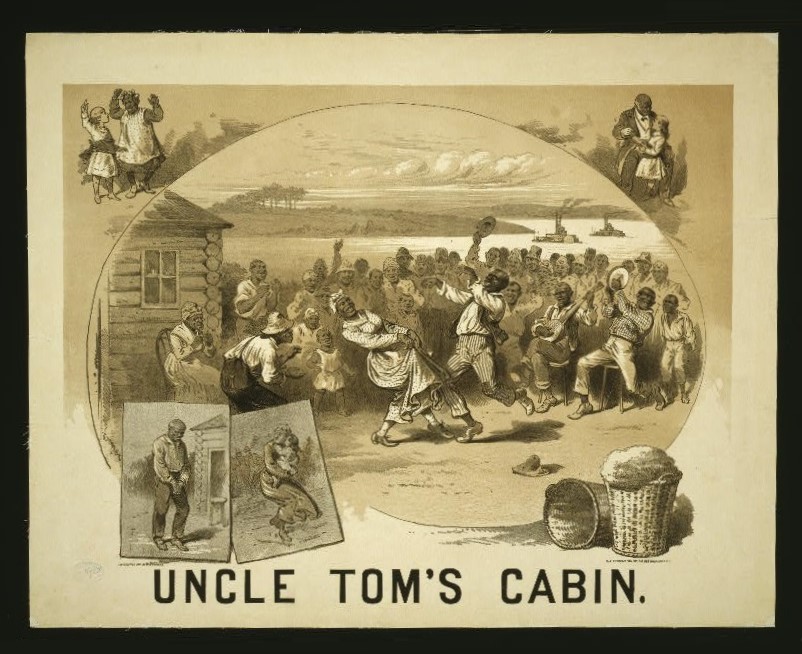

4.8. The Power of Popular Literature: Case Study 1: Uncle Tom’s Cabin

In 1862, the United States was in the second year of the Civil War. There is a famous story that when President Lincoln was introduced to Harriet Beecher Stowe in December of that year, he said, “So this is the little lady who started this great war” — or, depending on the account, something along those lines (Vollaro 2009, p. 18). The jokey greeting is probably a fiction. It became known late in Stowe’s life, told not by Stowe but by some of her family. It does not appear in any written record before 1896. The point of the story is that Stowe was the author of a popular novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin or, Life Among the Lowly (1852). The book’s story of the mistreatment of enslaved Black people contributed to Northern anti-slavery sentiment. However, the dominant culture of the North did not fully embrace the book, at least not in reviews and most published discussions of it. There was much concern that it was going to make it harder to continue the series of political compromises that were holding the country together (Vallaro 2009, p. 29). However, the Civil War broke out when militia of the breakaway state of South Carolina attacked U.S. troops at Fort Sumter in April, 1861. Until then, most people in the North had favored ongoing compromise. As noted earlier, this was especially true of the working class.

Stowe wanted to expose the horrors of slavery. Yet her book was not very different from the voice appropriation found in the plantation songs. The plot centers on cruel slave-owners who break up happy Black families, creating the impression that enslavement was not necessarily bad for enslaved people. Another problem is that many details of the book reinforce the racist stereotypes of the minstrel shows.

While historians debate just how much impact the novel had on the voting public, it was an astounding best-seller. It is likely that it sold more copies in the United States in the 19th century than any book other than the Bible. However, most of those sales came after the Civil War, and so its legacy has more to do with its long-term impact on American attitudes toward Black Americans and Southern life than with its possible impact on hastening the Civil War. The book’s influence as the best-selling fictional novel of the era was expanded many times over by its popularity as a stage play. (See figure 4.12.) By one estimate, there were a quarter-million theatrical performances of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the United States in the 19th century (Frick 2016, p. xiv). That translates into an average of 4,000 performances each year. By comparison, this is more than double the total worldwide performances of what is likely the most popular musical of the 20th century, The Phantom of the Opera. So, even if it did not actually contribute to the outbreak of the war, the novel encouraged several generations of Americans to think about Southern culture and Black identity in a specific way.

Like Cole’s landscape painting of the Connecticut River Valley and Moran’s paintings of the West, Uncle Tom’s Cabin is another example of the Romantic movement that arose in Europe and then reshaped American culture in the first half of the 19th century. The common thread is the growing importance of sentiment or feeling as the basis for reaching the audience. Many people assume that it has always been the case that art aims to express and touch the emotions. However, art’s emotional impact was seldom treated as its primary value before the arrival of Romanticism, which taught that art should appeal “to impulse and emotion, not order and calm” (Brooks 2019, p. 7). Sublime landscapes do this by inducing awe. In contrast, Stowe’s novel aims at sympathy, placing it in the category of the sentimental melodrama. She appropriated much of her content from true stories, including published accounts by enslaved people who had escaped to the North. (See the parallel example provided in Chapter 6, Section 6.5.) She also borrowed from other popular melodramas. The most obvious case is that the death of Uncle Tom’s beloved Eva is modeled on the death of Little Nell in Charles Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop (1840) (Parini 2010, p. 146).

As her book’s title makes clear, Stowe’s many appropriations are stitched together by the central story of a deeply Christian enslaved man, Uncle Tom. Unfortunately, the result is a racist text. Instead of treating ethnic differences as a matter of learned cultural identities, Stowe endorses the idea that different cultures are expressions of racial (biological) identity. For example, Tom is beaten to death by his owner, Simon Legree, because Tom will not reveal the hiding place of Cassy and Emmeline, two enslaved women who were attempting escape. Stowe describes Tom’s horrible death as a “glorious” Christian martyrdom. Tom dies because, as a good Christian, he will sacrifice himself for others. As he’s being killed, Tom says to Legree, “Mas’r, if you was sick, or in trouble, or dying, and I could save ye, I’d give ye my heart’s blood; and, if taking every drop of blood in this poor old body would save your precious soul, I’d give ’em freely, as the Lord gave his for me. O, Mas’r! don’t bring this great sin on your soul! It will hurt you more than ’t will me! Do the worst you can, my troubles’ll be over soon; but, if ye don’t repent, yours won’t never end!” (Stowe 1852, p. 273).

21st-century readers might suppose that Stowe is undercutting racism by making Tom more noble than the book’s villain, a White slave owner. However, a different message emerges when Tom’s martyrdom is placed in the context of the book’s ending. George Harris, a mixed-race character, is released from slavery and he eventually becomes “an educated man” (Stowe 1852, p. 299). The book then offers a long letter he has written, endorsing the emigration of Black Americans to Africa. It is hard to read this passage without seeing it as a voice appropriation in which the character is meant to represent a larger group, namely any formerly enslaved Black person who examines the situation calmly and rationally.

Excerpt from George Harris’ letter, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Chapter XLIII

The desire and yearning of my soul is for an African nationality. I want a people that shall have a tangible, separate existence of its own; and where am I to look for it? … On the shores of Africa I see a republic, — a republic formed of picked men, who, by energy and self-educating force, have, in many cases, individually, raised themselves above a condition of slavery. … Let us, then, all take hold together, with all our might, and see what we can do with this new enterprise, and the whole splendid continent of Africa opens before us and our children. Our nation shall roll the tide of civilization and Christianity along its shores, and plant there mighty republics, that, growing with the rapidity of tropical vegetation, shall be for all coming ages. …

I think that the African race has peculiarities, yet to be unfolded in the light of civilization and Christianity, which, if not the same with those of the Anglo-Saxon, may prove to be, morally, of even a higher type. To the Anglo-Saxon race has been intrusted the destinies of the world, during its pioneer period of struggle and conflict. … I trust that the development of Africa is to be essentially a Christian one. If not a dominant and commanding race, they are, at least, an affectionate, magnanimous, and forgiving one. …

In myself, I confess, I am feeble for this, — full half the blood in my veins is the hot and hasty Saxon; but I have an eloquent preacher of the Gospel ever by my side, in the person of my beautiful wife. When I wander, her gentler spirit ever restores me, and keeps before my eyes the Christian calling and mission of our race.

Here, Stowe’s voice appropriation has a central Black character endorse the idea that one race, the Anglo-Saxon, has a racial destiny to rule the world at the present time. African peoples, on the other hand, are by nature “affectionate, magnanimous, and forgiving.” They are, therefore, more naturally fitted to the practice of Christianity. Uncle Tom’s self-sacrifice and martyrdom is now explained by appeal to the racial traits of Black people. Voicing a common abolitionist idea, George wants Black Americans to return to Africa in order to convert the entire continent to Christianity. The core idea is that different races have distinct personalities, as if it is natural for White Americans to be slave-owners as long as there are Black Americans. At the same time, African cultures are in need of Christian transformation brought from America, implying that they remain uncivilized and cannot attain full civilization until they adopt European religious beliefs. Granted, Stowe has George endorse the moral superiority of Black Africans, but only on the grounds that they are racially susceptible to Christianity. Uncle Tom’s Cabin does not challenge racism. Instead, it illustrates how Americans adapted earlier stereotypes of Indigenous inferiority to the topic of slavery.

The book’s racism is problematic, but the theatrical appropriations were even worse. As is typical, the appropriation process changed the material to make it more accessible to its intended audience. As noted, the novel makes Uncle Tom a Christian martyr who dies to help two Black women who had been sexually abused. However, “the stage depictions don’t include that part of the story. They grossly distort Uncle Tom into an older man than he is in the novel, a man whose English is poor, a man who will do quite the opposite, who will sell out any black man if it will curry the favor of a white employer, a white master, a white mistress” (Turner, quoted NPR, 2008). On stage, Uncle Tom was less like the hero of the book and more like a character in a minstrel show. Theatrical producers wanted the biggest possible paying audiences. By changing Uncle Tom to fit the Jim Crow stereotype, a story that originally appealed to Northerners became popular in the South, as well. In the long run, changing the story to conform to common prejudices meant that Stowe’s work became a platform for long-term reinforcement of those racial stereotypes. Many theatrical performances also incorporated song and dance, often taken directly from minstrel shows. In particular, Stephen Foster’s nostalgic plantation songs continued to circulate well into the Jim Crow era, and their appropriation reinforced the idea that enslaved people might be happy as long as their owners were not especially abusive (Frick, pp. 2, 13, 256).

4.9. The Power of Popular Literature: Case Study 2: Hiawatha

Another popular literary work of the 1800s is a book-length poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Published in 1855, shortly after Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha is a tragic story about the Ojibwa people of the Lake Superior region. A descendant of one of original colonizers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Longfellow appropriated both the basic poetic meter and much of its content from Ojibwa storytelling and legends. Like so much art of this period, the poem was also influenced by European Romantic thought and art. One of the key background ideas was that so-called “primitive” people lived a more natural lifestyle than “civilized” Europeans. In particular, the Romantic movement viewed Indigenous peoples as more attuned to nature, less materialistic, and consequently more deeply spiritual. At the same time, writers like Longfellow downplayed the degree to which different Indigenous peoples had distinctive, evolving cultures. Treating them as relics frozen in their traditional past, Longfellow joined the chorus of American writers who portrayed them as a heroic but doomed race.

The poem was criticized by early reviewers as boring and because it focused on Indigenous peoples. The New York Times criticized it for relating “the monstrous traditions of an uninteresting, and, one may almost say, a justly exterminated race” (anonymous, 1855). However, it proved to be popular with the general public and soon sold 50,000 copies. It reached an even larger public through serialization in newspapers. The book and its serialization made Longfellow a wealthy man. The poem became a common fixture of American education, and generations of students formed their basic view of Indigenous peoples from their exposure to it. Like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it also became the basis of many stage plays and, later, several film adaptations.

Excerpts from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha (1855)

Introduction

… Listen to this Indian Legend,

To this Song of Hiawatha!

Ye whose hearts are fresh and simple,

Who have faith in God and Nature,

Who believe that in all ages

Every human heart is human,

That in even savage bosoms

There are longings, yearnings, strivings

For the good they comprehend not,

That the feeble hands and helpless,

Groping blindly in the darkness,

Touch God’s right hand in that darkness

And are lifted up and strengthened; —

Listen to this simple story,

To this Song of Hiawatha! …

Chapter 5. Hiawatha’s Fasting

… And behold! the young Mondamin,

With his soft and shining tresses,

With his garments green and yellow,

With his long and glossy plumage,

Stood and beckoned at the doorway.

And as one in slumber walking,

Pale and haggard, but undaunted,

From the wigwam Hiawatha

Came and wrestled with Mondamin. …

Suddenly upon the greensward

All alone stood Hiawatha …

And before him breathless, lifeless,

Lay the youth, with hair dishevelled,

Plumage torn, and garments tattered,

Dead he lay there in the sunset.

And victorious Hiawatha

Made the grave as he commanded,

Stripped the garments from Mondamin,

Stripped his tattered plumage from him,

Laid him in the earth, and made it

Soft and loose and light above him…

Till at length a small green feather

From the earth shot slowly upward,

Then another and another,

And before the Summer ended

Stood the maize in all its beauty …

Then he called to old Nokomis

And Iagoo, the great boaster,

Showed them where the maize was growing,

Told them of his wondrous vision,

Of his wrestling and his triumph,

Of this new gift to the nations,

Which should be their food forever. …

This new gift of the Great Spirit.

Chapter 11 The Wedding Feast

… Sumptuous was the feast Nokomis

Made at Hiawatha’s wedding;

All the bowls were made of bass-wood,

White and polished very smoothly,

All the spoons of horn of bison,

Black and polished very smoothly.

She had sent through all the village

Messengers with wands of willow,

As a sign of invitation,

As a token of the feasting;

And the wedding guests assembled,

Clad in all their richest raiment,

Robes of fur and belts of wampum,

Splendid with their paint and plumage,

Beautiful with beads and tassels. …

And the gentle Chibiabos

Sang in accents sweet and tender,

Sang in tones of deep emotion,

Songs of love and songs of longing;

Looking still at Hiawatha,

Looking at fair Laughing Water,

Sang he softly, sang in this wise:

“Onaway! Awake, beloved!

Thou the wild-flower of the forest!

Thou the wild-bird of the prairie!

Thou with eyes so soft and fawn-like!

“If thou only lookest at me,

I am happy, I am happy,

As the lilies of the prairie,

When they feel the dew upon them!”

Chapter 22 The Departure [Final Chapter]

O’er the water floating, flying,

Something in the hazy distance,

Something in the mists of morning,

Loomed and lifted from the water,

Now seemed floating, now seemed flying,

Coming nearer, nearer, nearer. …

But a birch canoe with paddles,

Rising, sinking on the water,

Dripping, flashing in the sunshine;

And within it came a people

From the distant land of Wabun,

From the farthest realms of morning

Came the Black-Robe chief, the Prophet,

He the Priest of Prayer, the Pale-face,

With his guides and his companions.

And the noble Hiawatha,

With his hands aloft extended,

Held aloft in sign of welcome,

Waited, full of exultation,

Till the birch canoe with paddles

Grated on the shining pebbles,

Stranded on the sandy margin,

Till the Black-Robe chief, the Pale-face,

With the cross upon his bosom,

Landed on the sandy margin.

Then the joyous Hiawatha

Cried aloud and spake in this wise:

“Beautiful is the sun, O strangers,

When you come so far to see us! …

All our town in peace awaits you,

All our doors stand open for you;

You shall enter all our wigwams,

For the heart’s right hand we give you.

Never bloomed the earth so gayly,

Never shone the sun so brightly,

As to-day they shine and blossom

When you come so far to see us!” …

And the Black-Robe chief made answer,

Stammered in his speech a little,

Speaking words yet unfamiliar:

“Peace be with you, Hiawatha,

Peace be with you and your people,

Peace of prayer, and peace of pardon,

Peace of Christ, and joy of Mary!” …

Then the Black-Robe chief, the Prophet,

Told his message to the people,

Told the purport of his mission,

Told them of the Virgin Mary,

And her blessed Son, the Saviour,

How in distant lands and ages

He had lived on earth as we do;

How he fasted, prayed, and labored;

How the Jews, the tribe accursed,

Mocked him, scourged him, crucified him;

How he rose from where they laid him,

Walked again with his disciples,

And ascended into heaven.

And the chiefs made answer, saying:

“We have listened to your message,

We have heard your words of wisdom,

We will think on what you tell us.

It is well for us, O brothers,

That you come so far to see us!”

Then they rose up and departed

Each one homeward to his wigwam,

To the young men and the women

Told the story of the strangers

Whom the Master of Life had sent them

From the shining land of Wabun. …

From his place rose Hiawatha …

Forth into the village went he,

Bade farewell to all the warriors,

Bade farewell to all the young men,

Spake persuading, spake in this wise:

“I am going, O my people,

On a long and distant journey;

Many moons and many winters

Will have come, and will have vanished,

Ere I come again to see you.

But my guests I leave behind me;

Listen to their words of wisdom,

Listen to the truth they tell you,

For the Master of Life has sent them

From the land of light and morning!” …

Thus departed Hiawatha,

Hiawatha the Beloved,

In the glory of the sunset,.

In the purple mists of evening,

To the regions of the home-wind,

Of the Northwest-Wind, Keewaydin,

To the Islands of the Blessed,

To the Kingdom of Ponemah,

To the Land of the Hereafter!

[end]

The story of Hiawatha’s struggle with the spirit Mondamin in Chapter 5 is just one among many examples of content appropriation in The Song of Hiawatha. Longfellow took this story from a collection of Indigenous legends published by Henry Schoolcraft (Thompson 1922). However, Schoolcraft obscured the degree to which he was rewriting traditional legends that he learned from his wife, Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, whose mother was Ojibwa (Holmes 2021, Parker 2008). In the process, Schoolcraft “substantially distorted” what he learned from his wife (Lockard 2000, p. 111). As a result, much of Longfellow’s poem emerges from two distinct stages of voice and content appropriation: Henry Schoolcraft revises what he learns from Jane Schoolcraft to make it more appealing to the dominant culture, then Longfellow does the same again when borrowing from that material.

Notice, for example, the strange historical distortion of placing the Mondamin tale into the poem. Based on the date of arrival of Roman Catholic missionaries in upper Michigan in the late 17th century, Longfellow is proposing that the cultivation of corn also arrived in the 17th century. In this way, Longfellow subverts Indigenous tradition, which says that the stories tell of an ancient time. However, the idea that the Ojibwa people had raised crops for many centuries would undercut the claims of “discovery” and ownership of this region by the French, then the British, then the Americans. In Longfellow’s appropriation, agriculture arrives just before the French missionaries.

Chapter 11 of the poem is original material. As a result, it is full of completely fabricated voice appropriation, and it seriously misrepresents the culture it portrays. In reality, Ojibwa and related cultures did not have formal “marriages” and did not celebrate them with elaborate feasting. They had “recognized relationships, akin to common-law marriages, rather than formal, licensed marriages. … The formal wooing and wedding plot in Hiawatha was a thoroughly European story dressed in the costumes of Native Americans” (National Park Service, no date). Longfellow probably aimed to make Hiawatha more acceptable to the dominant culture by centering the story in a romance narrative reflecting their own traditions.

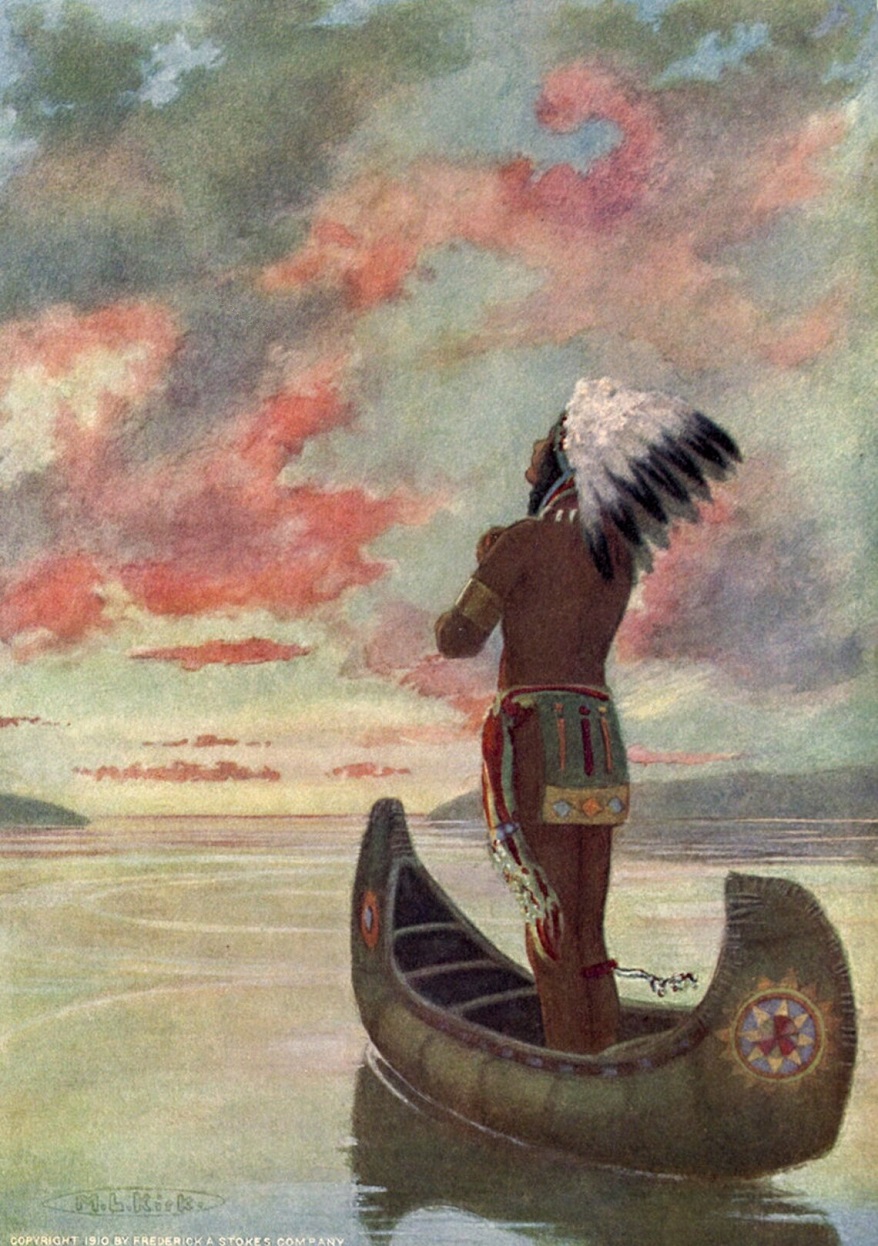

Longfellow ends the poem with another act of cultural assimilation. Using voice appropriation, Longfellow positions Hiawatha as endorsing Christianity and Manifest Destiny. Then, the hero steps into a canoe and sails west to his death, “the land of the Hereafter.” (See figure 4.13. Note the motif appropriation at work in this picture: headdresses of the kind seen here were unknown among the Ojibwa people at the time the story takes place.)

The ending is perhaps the most hurtful voice appropriation of the whole poem. With the arrival of Christianity, Hiawatha simply accepts the termination of Indigenous culture. Symbolically, this is a revision of American history that wipes out the ugliness of active genocide, theft of land, and Indigenous resistance. Published and enjoyed during the period when the frontier continued to feature ongoing Indigenous resistance to U.S. expansion, The Song of Hiawatha implies that noble tribes surrender their land and ways without a fight. As Joe Lockard puts it, “The epic’s Indian demigod hero disappears, an epoch and a culture come to an end, and Longfellow’s believing readers continue on, conscience fortified, into the continuum of a bland and perfected American history” (Lockard 2000, p. 112).

4.10. Conclusion

As the United States pushed westward, it embraced the ideology that a democracy-loving race of European ancestry had a God-given duty to possess and rule the continent. This doctrine was spread in both fine art and popular art, influencing how the dominant culture thought about other societies and cultures. During this time, Mexico gained its independence from Spain and ruled the Southwest from Texas to California. Indigenous peoples still controlled much of the remainder. However, the Southern states wished to expand their slave-based economy into lands held by Indigenous peoples and then into Mexican territory. Expansion was also favored by the growing population of the North, swelling with new immigrants. Seeking to justify land appropriation while also keeping the Union together, the dominant culture developed a “White” national identity that contrasted a “traditional” dominant culture with negative stereotypes of Black people, Hispanics, and Indigenous peoples. Distinct stereotypes were assigned to different groups, yet they shared the common theme that democratic self-governance was reserved for the racially superior dominant culture. This message was often communicated in a symbolic manner that appropriated European symbolism and art innovations. Notably, this included visual symbolism that represented the land itself as calling out for possession and development by the dominant culture.