2 Race, Ethnicity, and the American Social Fabric

Theodore Gracyk

Authorship

This is an edited, expanded, extensively rewritten version of Unit 11, “Race and Ethnicity,” of the book Introduction to Sociology 2e, written by Heather Griffiths, Eric Strayer, Susan Cody-Rydzewski, and others, and published by OpenStax College, 2015. This material is published and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. Access original text for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology. All material has been edited, updated, rewritten, and expanded by Theodore Gracyk.

2.1. Overview

- Understand the difference between race and ethnicity

- Define a majority group (dominant group)

- Define a non-dominant ethnic group

- Define racism

- Recognize America’s ethnic diversity

Many people use the terms “race,” “ethnicity,” and “minority group” more or less interchangeably. However, these three terms have very distinct meanings for sociologists, anthropologists, historians, and others who study human social life. The idea of race refers to observable physical differences that a particular society uses as a basis for assigning group identity. In contrast, ethnicity describes shared culture, generally tracing back to shared ancestry. The term “minority group” is a common phrase for groups that are lack power in a particular society, regardless of skin color or country of origin. For example, in modern U.S. history, people with severe hearing impairment count as a minority group due to a diminished status that results from popular prejudice and discrimination against them. The present chapter explains and critiques common views of race and racism.

2.2. What Are Race and Ethnicity?

One thing about race must be stated clearly, up front. Research in genetics, history, anthropology, and sociology converge on the view that race is not biologically identifiable. Nonetheless, racial thinking continues to affect our lives.

Historically, the concept of race has changed across cultures and eras. The word “race” entered European languages around 1500, but it did not mean what it does today. For at least two centuries after the word was introduced, no one would have said that the members of three unrelated families living in different countries — Ireland, France, and Norway, for example — share the same race. For example, shortly before the United States broke from England and became a new country, its primary meaning was to designate a family (Johnson 1755). According to this primary usage, the many generations of Englishmen who inherited the title of Duke of Buccleuch and associated land holdings did so based on their “race.” A different race of Englishmen inherited the Dukedom of Beaufort (established 1682). And, of course, both families would have been considered different races from the servants and agricultural laborers who worked for them. During this time, “race” could also mean a specific generation of people, so that baby boomers and Gen Z might be referred to as different races.

The English word “race” settled into its current meaning during the 18th century (Curran 2011). Race came to refer primarily to phenotype, that is, widely shared physical appearances. Multiple families and ethnic groups were then grouped together as members of the same race based on the twin factors of appearance and geography. The principles of genetic inheritance were not yet known, and intellectuals wrongly argued that other inherited differences must accompany differences in skin color, eye color, and so on. In 1790, the United States limited citizenship for immigrants to “free White” people. For the next two centuries, American courts could not agree on who counted as White, frequently using an immigrant’s religion as the basis for deciding (Wills 2020).

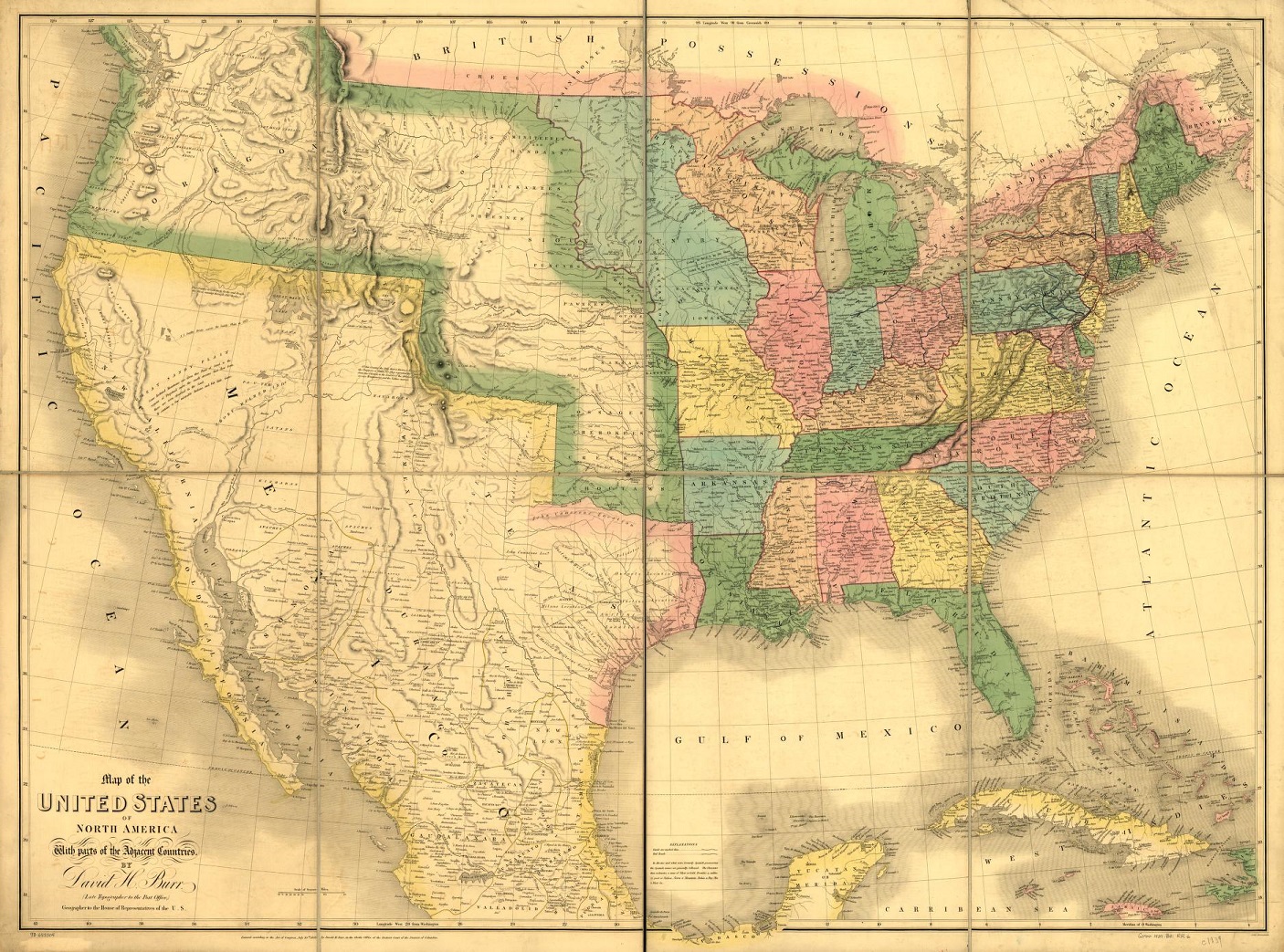

At different times and for different reasons, people have posited categories of race based on various geographic regions, ethnicities, skin colors, and more. The original meaning of race assumed that there were many, many races. This openness was replaced by the modern view that there are four basic races, each associated with a geographic region: European Whites, East Asians, sub-Saharan or Black Africans, and Indigenous Americans. (See figure 2.1.) This view became relatively standard after being proposed by Carl Linnaeus in the second half of the 18th century. In the years that followed, the four were generally expanded into five (and sometimes six) basic racial groups.

What explains this change in the concept of race, so that it shifted from direct family ancestry to the idea that there are only a handful of races? To a large extent, race was redefined because Europeans colonized Africa, the Americas, and then Asia and the Pacific. Race lost its connection to direct ancestral and familial ties. It became more concerned with the doctrine that Europeans were superior to the visually distinguishable peoples they conquered and colonized. This was explicit in Linnaeus, who assigned innate, positive character traits to Europeans and Indigenous Americans but highly negative ones to East Asian and Black African populations. As Chike Jeffers explains, races “as we now know them … are appearance-based groups that initially resulted from the history of Europe’s imperial encounter” (Glasgow, Haslanger, Jeffers, and Spencer 2019, p. 65). Modern racial classifications became more fixed as Europeans subjugated the other continents and imposed European cultural standards. The assumption that the world contains a small handful of biological ancestries functioned as a tool for justifying social hierarchies. In other words, modern racial categories were imposed on people in order to justify racist practices (Omi and Winant 1994; Graves 2003).

In the United States, racial classifications became increasingly important to distinguish the colonizers from the Indigenous population and from the people brought from Africa and enslaved (Baum 2006, pp. 44-49, 95-99). In other words, because the American political and economic system relied on a denial of equal rights to Indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans, it became increasingly common to justify land appropriation, genocide, and slavery by appeal to race. Discussions of race became explicitly racist. The dominant ethnic groups claimed that racial differences create a natural hierarchy of races in which “Whites” have inherent rights that can be enforced at the expense of other groups. In this context, American culture assigned an underlying “Caucasian” identity to European immigrants who would not have agreed that they all belonged to the same race before their arrival in North America.

This historical background points to the conclusion that racial classification is a social construction. In other words, racial categories are really social distinctions presented as biological or otherwise natural categories. Modern genetics and the human genome project indicate that everyone shares so much common DNA that biological differences involve only a fraction of our DNA. Within that small fraction of difference, there are no clusters of DNA that align people according to modern racial categories. For example, if we examine the DNA of two randomly selected people in sub-Saharan Africa, their degree of divergence from one another will probably be greater than their divergence from any randomly selected person from a different continent and “race” (Rattansi 2020, pp. 36-37). To put it another way, there are more genetic differences among “Black” Africans than between sub-Saharan Africans and “Caucasians” (Yu et al. 2002).

In the United States, skin color or pigmentation has been a major tool of racial classification. Although many human traits are influenced by genetics, the eight genetic variations that determine skin pigmentation are not part of some larger, distinctive package of difference. We now know that the relative darkness or fairness of skin is an evolutionary adaptation to the available sunlight in different regions of the world. But this adaptation is completely independent of the DNA that underlies intelligence and social traits.

Summing Up: Race Is A Mistaken Idea

To put it as clearly as possible, racial classifications have a social and political function, but they don’t capture any important differences among people. The fact that two people have shared ancestry and similar physical appearances doesn’t provide any evidence that those two people are similar in any other ways.

There is no biological relationship between something called “race” and the cultural patterns that we find in ethnic groups, that is, in groups of people with shared ancestry who are socially organized around a shared culture.

There is one reason why racial classifications were developed and continue to be used, and that reason is to promote racism.

Racism teaches that skin color correlates biologically with distinctive behavioral and mental traits. (To put it another way, it teaches that because ancestry confers distinctive patterns of physical traits, such as eye color and skin color, ancestry must also confer distinctive patterns of other traits, such as intelligence.) However, those links don’t exist, that is, there is no actual biological or other evidence of any relationship between skin color and behavioral and mental traits. People who continue to endorse racism do so to excuse the ongoing mistreatment of specific social groups.

2.3 If “Race” Isn’t Real, Does it Matter How People Get Classified?

Once it became clear that races don’t exist as a matter of biological fact, some institutions began to admit that racial identities are social constructs. The United States Supreme Court said as much in 1923. For legal purposes, such as enforcement of immigration and citizenship laws, race could not be determined by reference to biological facts. Henceforth, someone was White, or not, based on how “the common man” would classify them (United States v. Thind 1923). The court admitted that races aren’t biologically real, yet allowed racial categorization to continue be used in the assignment of various rights. To make things even more confusing, the U.S. government started to use “race” and “ethnicity” as equivalent terms on census questionnaires beginning in 2024.

The continuing assignment of race by “the common man” affects everyone. First, it shapes a person’s social identity. Second, it influences one’s sense of personal identity. Third, it affects how others are likely to treat you throughout your life.

Here is a typical explanation of the distinction between personal identity and social identity:

Humans have the capacity to define themselves not simply as individuals (i.e., in terms of personal identity as “me” and “I,” with unique traits, tastes and qualities) but also as members of social groups (i.e., in terms of social identity as “we” and “us,” e.g., … “we Americans”) [and] understandings of self that result from internalizing social identity are qualitatively distinct from those which flow from personal identities. This is primarily because social identities restructure social relations in ways that give rise to, and allow for the possibility of, collective behavior. (Haslam et al. 2023, p. 3)

Social identity influences the ways that other people perceive and treat someone. For example, racial profiling by law enforcement is a well-documented fact of American life, and it adversely impacts the lives of many Black Americans. Racial classifications can influence an individual’s understanding of their personal identity. An “internalization” of social expectations can affect a person’s self-understanding of what they can, and cannot, accomplish in life.

To put it another way, the practice of assigning traits, abilities, and psychological profiles to people based on race has no basis in biological fact. Yet the mistaken assumption that there are racial patterns for these things tends to generate a self-fulfilling prophecy. People stereotyped as less intelligent due to their racial classification might put less effort into education: they may internalize the stereotype as a part of their personal identity and doubt their own ability to do well in school. At the same time, teachers may put less effort into their education because the social identity of these individuals predicts that the effort will be wasted.

To break the cycle of harmful consequences of racial classification, it is crucial for everyone to understand that racial identity is a social construct and therefore not fixed in anyone’s “blood,” ancestry, or genetic makeup.

None of this is to deny that there are variations in DNA sequences that permit identification of someone’s biological relatives and general ancestry. However, the results are not always what people have been taught to expect.

For example, until recently it was commonly taught that the early Britons of present-day England were largely replaced by Northern European settlement during the Medieval period. As a result, the English are often claimed to be descendants of Anglo-Saxon invaders and settlers, and therefore so were the revolutionaries who created the United States. However, DNA testing reveals that this never happened. Few people in England have or have ever had a predominantly Anglo-Saxon ancestry (Siddique 2016, Leslie et al. 2015). The common idea that the English settlers who colonized North America were Anglo-Saxon is therefore also a myth.

What the genetic markers reveal about the ancestry of people in England is surprisingly more fine-grained than a division between Anglo-Saxons and others. In England, people with 50% or greater Anglo-Saxon ancestry are concentrated in one place: north-east England. Beyond that small pocket, Anglo-Saxons intermarried with people to their south (but not to their north or west), so that many people in central England have 10 to 40% Anglo-Saxon ancestry. But this does not mean that the remainder of England is unified by descent from a single genetic group that predated the Anglo-Saxons. Studies have been conducted in all parts of England, especially in rural areas where historically there was limited immigration or marriage outside the local district. One finding is that rural people of Devon and Cornwall (in Southwest England) share a great deal of common ancestry. However, they do not share this distinct ancestry with the rural families of Dorset, which is the county immediately to their east (Ghosh 2015, Leslie et al. 2015).

These genetically distinct clusters of people are all considered traditionally “English,” yet DNA testing shows no unifying ancestry across a range of English rural counties. So, it is true that genetic analysis can reveal ancestry. However, genetics undercuts the claim that there is shared “English” or “White” ancestry among people who identify as English. There is English ethnicity, but no underlying English race. The same result holds among people who self-identity as Celtic: there is no ancestral connection unifying the various groups who claim to have a common Celtic past (Leslie et al. 2015).

Although they have no basis in human biology, our current racial classifications emerged and became popular because the practice is used to justify the (false) belief that cultural differences are inherited and inherent. Consider the stereotype that Germans lack a sense of humor. When we notice that a new coworker is overly serious, businesslike, and doesn’t joke around, it might be explained by saying, “Schmidt can’t help it. Germans have no sense of humor.” This might be a claim that Schmidt is that way as an inherited tendency of the German “race.” (Notice, however, that if this is an appeal to race, then it requires seeing Germans as distinct from other “White” Europeans. Racial stereotypes show us that racial boundaries are fluid.) But it might, instead, be a reference to ethnicity. Schmidt was brought up to be that way, because it’s part of German ethnicity. For centuries, these two explanations have been assumed to be related, with race as the (supposed) foundation of ethnic traits, some of which are assumed to be more desirable than others. That view of human traits and ancestry is false, and it is the core problem of confusing race and ethnicity.

Ethnicity is a term that references a group’s cultural commonalities — the practices, values, and beliefs of a group due to its social organization around a shared ancestry. Commonalities in the upbringing of children of the same ethnic group will encourage them to have a shared sense of humor. However, no ethnic group passes along DNA that makes it more or less likely that their ethnic group will enjoy a good joke.

To be very clear: ethnic differences are not the “natural” expression of shared “racial” ancestry. Race and ethnicity are historical and social constructs. They are distinctions created and maintained for social purposes. (Social constructs are also known as institutional facts.) For example, the borders between the United States and its neighbors are social constructs. They were not created by “nature.” They have changed over time. They exist only by social agreement. This does not mean they are not real. In some places, crossing a border without permission can get you thrown in prison. Driving is another good example. There is no “natural” side of the road for driving. (See figure 2.2.) However, once one is trained into a socially-enforced system, that system becomes second-nature and is difficult to escape.

As with the rules of the road, many social constructs are well-defined and regulated. Examples of well-defined constructs include U.S. citizenship, the marital status of being divorced, and the educational status of possessing a baccalaureate degree. At the level of specific cases, consider the fact that the current lifetime home run record of American baseball was set on September 5, 2007. Notice how many complex social institutions are woven together here. The truth of that claim depends on the calendar in use, the rules of baseball, and the distinction between the United States and other countries. This one social or institutional fact depends on the population’s acceptance of multiple complex social norms. In contrast, many other social constructs are less well-defined, such as whether a joke is in bad taste, or whether a movie is a children’s movie, or how much money someone needs to be “middle class.” Although there are plenty of unclear or borderline cases, it is a social fact that Barney’s Great Adventure (1999) is a children’s movie. It is a social or institutional fact that someone whose annual income is below $20,000 is not part of America’s middle class.

In a parallel fashion, the United States developed complex, distinctive social institutions that assign racial status to individuals. People who are considered White in other parts of the world are often surprised to learn that they count as Black in the United States. In particular, the system of racial classification developed in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of South and Central America is different from the American model (Taylor 2013, p. 54).

The lesson here is that race is a social construct, created and sustained through social expectations and institutions. Whether well-defined or loosely-defined, these constructs have real-world consequences. Many consequences are aligned with the social-constructs of race, ethnicity, and of dominant group status.

2.4 What is a Non-dominant Group?

With only a few exceptions, most societies contain minority groups, including non-dominant ethnic groups. In today’s world, the dominant group commonly assumes it is unified by its racial identity and assigns different racial identities to non-dominant ethnic groups. In addition, it is often the case that the dominant society singles out other groups and its members for discriminatory treatment, such as those with mental illnesses. Normally, non-dominant groups are fully aware that its members are “objects of collective discrimination” (Wirth 1945, p. 347). According to a widely-accepted framework, a minority group is distinguished by five characteristics: (1) unequal treatment and less power over their lives, (2) distinguishing physical or cultural traits like skin color or language, (3) involuntary membership in the group, (4) awareness of subordination, and (5) high rate of in-group marriage (Wagley and Harris 1958).

Although “minority group” was the standard phrase for decades, many writers and researchers have stopped using this phrase. There are a number of reasons why it should be replaced by other phrases (Meyers 2007). For example, it suggests that “minority” is the opposite of “majority” and that the minority group cannot be the majority of the population. However, being a numerical minority is not a characteristic of being a minority group. There are many places where collective discrimination is directed against a group that is, in numbers, the largest ethnic group. For most of the 19th century, “territories” within the United States had majority Indigenous populations. (This fact explains why Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona did not become states until the twentieth century.) Yet these Indigenous peoples were minority groups under the normal meaning of the phrase. Today, there are several states where the White population is less than half the population, yet the White population remains the dominant group in economic and political terms.

In order to avoid confusion, it is generally better to use the phrase “oppressed group,” “subordinate group,” or “non-dominant” group” in place of “minority” group. Similarly, “dominant” is generally a better word than “majority.” Women outnumber men, yet men remain the dominant group. Whichever term is employed, they share the concept that the dominant group holds greater power in a given society, while non-dominant groups are those who lack power compared to the dominant group.

Because individuals belong to many socially-distinguishable groups, an individual can belong to the dominant group in one social setting and a non-dominant group in another setting. For example, a physically-handicapped White lawyer might belong to the dominant group in a professional setting, but will then experience discrimination as a member of a non-dominant group when needing physical access to the upper floors of a public building that lacks elevators.

In the same way that we identify non-dominant groups, we can also talk about non-dominant or minority cultures. The existence of non-dominant cultures is central to concerns about the morality of cultural appropriation.

2.5 What is Racism?

To summarize some key distinctions, race is fundamentally a social construct. It involves grouping people based on superficial features of appearance. Ethnicity is a term that describes shared culture and, generally, regional or national origin. Non-dominant groups are defined by their lack of power. In many societies there is a hierarchy among ethnic groups, so that one is dominant and others are non-dominant.

Racism is the use of racial categorization to identify non-dominant groups and to justify discrimination against them. Racism operates by using socially-constructed racial categories to defend the “naturalness” of social inequalities.

Jamelle Bouie has recently summarized the logic of racism in this way:

If some groups are simply meant to be at the bottom, then there are no questions to ask about their deprivation, isolation and poverty. There are no questions to ask about the society which produces that deprivation, isolation and poverty. And there is nothing to be done, because nothing can be done: Those people are just the way they are. (Bouie 2023)

In other words, racism is in place when the dominant group makes an ethnic group a target for systematic, unequal, discriminatory treatment and justifies that treatment by reference to race. Or, in the description of Ali Rattansi, racism is the modern belief that “biology and culture are intertwined in a form in which biological features are inevitably accompanied by cultural traits in particular populations” (Rattansi 2020, p. 2). According to racism, some people with shared ancestry are biologically disposed to be lazier than other people, and this explains the social phenomenon of their higher unemployment. Likewise, says the racist, some people with shared ancestry are biologically disposed to be more violent than other people, and this explains the social phenomenon of their higher rates of arrest and imprisonment.

It is important to note that the core element of racism is a set of beliefs. Prejudice is not part of the basic definition of racism. Unfortunately, racism and prejudice are frequently confused with each other. For example, some people will say things like, “I can’t be racist. I like Black music and I have Black friends.” While it is true that prejudice is a question of an individual’s views and responses to other people, racism is not simply a question of what happens at the level of individual response. Instead, racism is defined by reference to the larger social and cultural framework. When racism is present, it is present as part of social institutions and widespread social practices that involve race-based discrimination. For that reason, someone can lack prejudice and yet engage in racist behavior by going along with discriminatory norms.

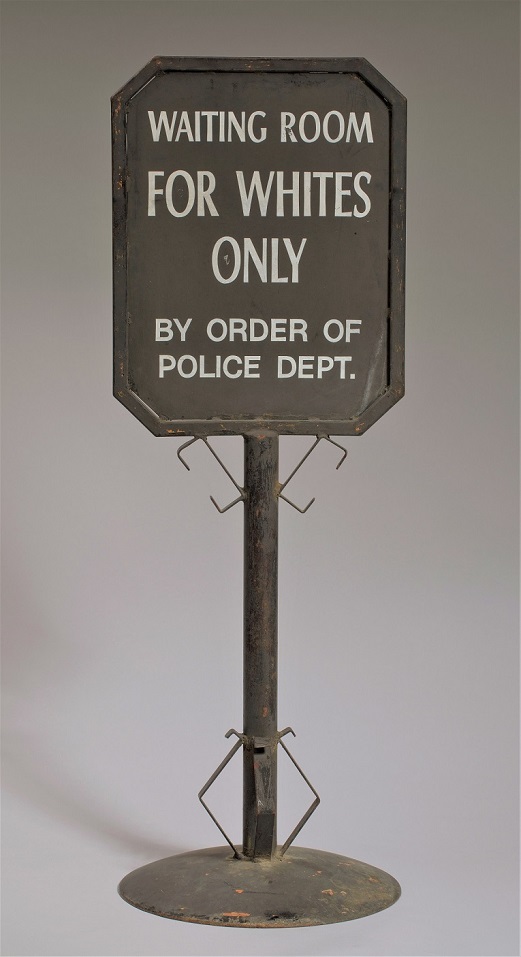

For this reason, sociologist Émile Durkheim calls racism a social fact, meaning that it does not require the direct support of individuals to continue. The reasons for this are complex and relate to the educational, criminal, economic, and political systems that exist in our society. Overt discrimination has long been part of U.S. history. In the late 19th century, it was not uncommon for business owners to hang signs that read, “Help Wanted: No Irish Need Apply.” Well into the twentieth century, Southern Jim Crow laws supported racial segregation, supported everywhere with “Whites Only” signs. (See figure 2.3). Meanwhile, some businesses in Texas posted signs reading “No Mexicans served,” meaning that even natural-born U.S. citizens were not to enter if they had Mexican ancestry. While this kind of overt discrimination is not tolerated today, less overt forms of segregation remain common. The social fact of racism can take many forms, from unfair housing practices, to biased hiring systems, to the practice of basing public school budgets on local property taxes and so providing much more support for public schools in predominantly White areas. By being built into policies and institutions, the social fact of racism becomes less visible.

Racism is also found in art and popular art produced by the dominant culture. Content appropriation and voice appropriation are especially powerful mechanisms for reinforcing the core idea of racism, which is that how someone looks reflects both their ancestry and their natural capacities.

Appropriation frequently takes the form of stereotypes and caricatures of non-dominant groups. These stereotypes often portray minorities as culturally inferior, justifying discrimination and mistreatment. Stereotypes can support both racism and racial prejudice. Since art frequently appeals to our emotions, demeaning stereotypes can spread prejudice. By making society’s racist practices appear normal, art can build support for the social fact of racism. Racist art both motivates and justifies an unjust, oppressive social system (Glasgow, Haslanger, Jeffers, and Spencer 2019, pp. 25-26).

Understood in this way, even a fashion accessory can be racist. In January 2006, two girls walked into Burleson High School in Texas carrying purses decorated with images of Confederate flags. (See figure 2.4.) School administrators told the girls that they were in violation of the dress code, which prohibited apparel with inappropriate symbolism or clothing that discriminated based on race. To stay in school, they’d have to have someone pick up their purses or leave them in the office. The girls chose to go home for the day but then challenged the school’s decision, appealing first to the principal, then to the district superintendent, then to the U.S. District Court, and finally to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Why did the school ban the purses, and why did it stand behind that ban, even when being sued? Why did the girls, identified anonymously in court documents as A.M. and A.T., pursue such strong legal measures for their right to carry the purses? The issue, of course, is not the purses: it is the Confederate flag that adorns them. The parties in this case join a long line of people and institutions that have fought for their right to display it, saying such a display is covered by the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech. The display of a symbol is a type of speech. However, the First Amendment does not guarantee the right to engage in certain kinds of disruptive speech, and it does not give people a right to engage in “speech” wherever they wish. In the end, the court sided with the district and noted that the Confederate flag carried symbolism significant enough to disrupt normal school activities. The girls lost in court.

While many people in the United States like to believe that racism is mostly in the country’s past, this case illustrates how racism and discrimination are quite alive today. If the Confederate flag is synonymous with support for slavery, is there any place for its display in modern society? Those who fight for their right to display the flag say such a display should be covered by the First Amendment: the right to free speech. But others look at its history and say that its display is equivalent to hate speech. There is no denying, however, that there are settings in which its appearance is disruptive. This was especially true at Burleson High School, where there was a past history of using the symbol to intimidate Black students as well as Black athletes from a rival school.

Two purses carried into a high school might seem like a trivial thing, but this action participates in, and supports, a racist strain within American culture. Someone doesn’t have to feel prejudice or identify as racist to advance racism. Someone doesn’t have to gain a personal advantage in order to participate in racism. To use a common expression, a lot of racism amounts to “going along to get along” as a member of a society’s dominant group. Racism secures systematic privilege of the dominant group through the oppression of other people based on grouping them by physical appearances. Culture, including art and adornment, can be an unintended tool of racism. Like it or not, the United States is a place where using a Confederate flag as a fashion accessory supports the social fact of racism.

2.6 Major Ethnic Groups in the United States

When Europeans came to the Americas, they called it the New World. However, they found a land that did not need “discovering” since it was already occupied. While the first wave of immigrants came from Western Europe, eventually the bulk of people entering North America were from Northern Europe, then Eastern Europe, then Latin America and Asia. And let us not forget the forced immigration of people from Africa in the slave trade. Most of these groups underwent a period of disenfranchisement in which they were relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy before they managed (for those who could) to achieve social mobility. Today, our society is multicultural. At the same time, the extent to which American diversity is embraced varies, and the many manifestations of multiculturalism carry significant political and cultural repercussions. The sections below will describe how several major groups became part of U.S. society and will summarize the current status of the group.

2.6.a Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous peoples are the only nonimmigrant ethnic group in the United States. They once numbered in the millions but today they are a small fraction of the U.S. populace. Counting those who identify themselves as either entirely or even partially of Indigenous ancestry, the total is just under 3% of the population (Rezal 2021). Given how systematically the U.S. relocated its Indigenous peoples westward as the nation expanded, the majority of them now live west of the Mississippi River, and in Alaska. Today, the largest groups are the Cherokee Nation (mostly in Oklahoma) and the Navajo Nation (mostly in New Mexico).

Indigenous culture prior to European settlement is referred to as Pre-Columbian: that is, prior to the coming of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Mistakenly believing that he had landed in the East Indies, Columbus named the indigenous people “Indians.” The name has persisted for centuries despite being a geographical mistake and one used for 500 distinct groups who each have their own languages and traditions. Except where it is unavoidable due to its past use, only tribal members should use “Indian” to refer to Indigenous people or their culture. Similarly, the phrase “Native American” is undesirable because “native” can suggest people who are uncivilized or primitive. In contrast, “Indigenous” is a neutral term that designates a presence prior to the arrival of colonizers.

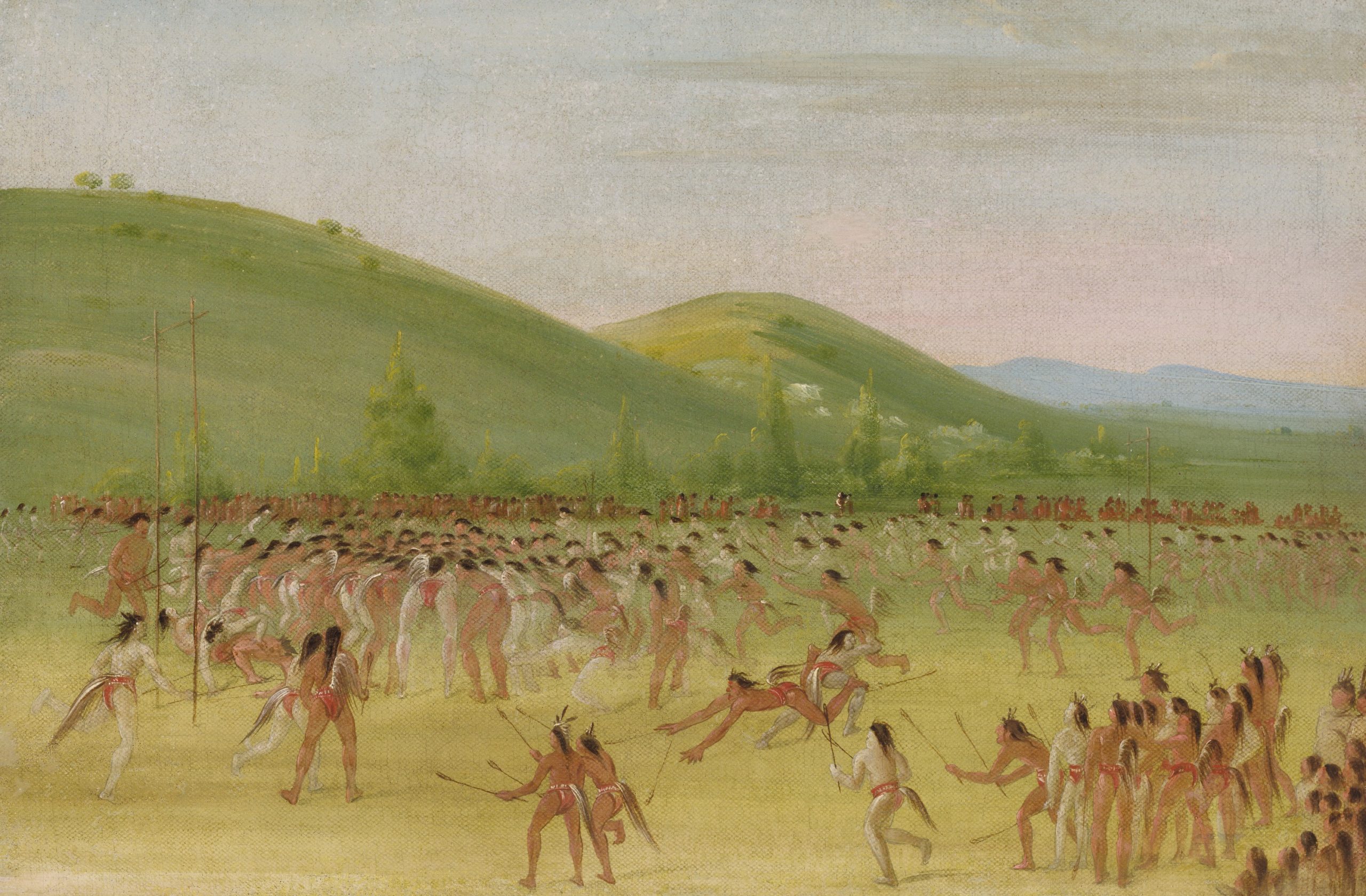

The history of inter-group relations between European colonists and Indigenous peoples is a brutal one. The Spanish sent their first military expeditions into the American Southwest in 1539 and 1540. Conquest followed. In 1607, the English established their initial settlement at Jamestown. In 1609, they adopted a policy of using military force to seize Indigenous food supplies to correct their own colonial mismanagement. As more Europeans arrived at multiple sites, warfare repeatedly broke out as Indigenous nations fought back against seizure of both land and people. Despite their resistance, the effect of European conquest of the Americas was to nearly destroy the Indigenous population. Although a lack of immunity to European diseases caused the most deaths, overt mistreatment by Europeans was systematic and devastating. Europeans’ domination of the Americas was indeed a conquest; one scholar points out that Indigenous Americans are the only group in the United States whose subordination occurred purely through conquest by the dominant group (Marger 1993).

From the first Spanish colonists to the French, English, and Dutch who followed, European settlers assumed they could take any land they wanted. If Indigenous people tried to retain their stewardship of the land, Europeans fought them off with superior weapons. The result was four hundred years of constant warfare in North America (Dunbar-Ortiz 2015, Hamalainen 2022). A key element of this issue is the Indigenous view of land and land ownership. Most Indigenous traditions consider the earth a living entity whose resources they were stewards of. Therefore, the concepts of land ownership and conquest didn’t exist in the way it did in European society. In response, European governments declared the land “empty” and “discovered” and available for taking and development. As a result, settlers could justify any action taken against Indigenous peoples who defended their land and their rights.

After the establishment of the United States government, discrimination against Indigenous peoples was codified and formalized in a series of laws and court rulings intended to subjugate them and keep them from gaining any power. Some of the most impactful laws and rulings are as follows:

- In a Supreme Court ruling in the case of Johnson v. McIntosh of 1823, the court ruled that the colonial “doctrine of discovery” was the law of the land. Basically, the court ruled that land belongs to whoever discovers it first, and only discovery by White people counted as discovery. Therefore, the Indigenous Nations do not own any land they occupy and it could be seized by those who “discovered” it as the United States spread west.

- The Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced the relocation of any Indigenous peoples east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river.

- The Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 funded further removals and reversed the long-standing recognition of Indigenous groups as independent nations. As a result of the act, the U.S. government would no longer enter into treaties. This made it even easier for the U.S. government to take land it wanted.

- The Dawes Act of 1887 reversed the policy of isolating Native Americans on reservations, instead forcing them onto individual properties that were intermingled with White settlers, thereby forcing assimilation and reducing their capacity for power as a group.

Indigenous culture was further eroded by the establishment of Indian boarding schools in the late 19th century. These schools, run by both Christian missionaries and the United States government, had the express purpose of “civilizing” Native American children and assimilating them into White society. The boarding schools were located off-reservation to ensure that children were separated from their families and culture. Schools forced children to cut their hair, speak English, and practice Christianity. Physical and sexual abuses were rampant for decades; only in 1987 did the Bureau of Indian Affairs issue a policy on sexual abuse in boarding schools. Some scholars argue that many of the problems that Native Americans face today result from almost a century of mistreatment at these boarding schools.

Beginning in the 1960s, Indigenous Americans began to participate in and benefit from the civil rights movement. The Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 guaranteed Indigenous peoples most of the rights of the United States Bill of Rights. New laws like the Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 and the Education Assistance Act of the same year recognized tribal governments and gave them more power. However, centuries of mistreatment cannot be reversed in a few decades. Long-term poverty, inadequate education, cultural dislocation, and high rates of unemployment contribute to Indigenous peoples falling to the bottom of the economic spectrum.

2.6.b Black Americans

Although it has been used for many years, the phrase African American does not fit many individuals. Many Americans with dark skin may have their more recent roots in Europe or the Caribbean, seeing themselves as Dominican American or Dutch American. The Black Lives Matter movement has revived the term Black as an inclusive term for a broad range of people whose ancestry originates in sub-Saharan Africa. Currently, the U.S. Census Bureau (2020) estimates that 13.6 percent of the United States’ population is Black.

This section will focus on the legacy of people who were transported from Africa and enslaved in the United States, and their descendants. The Spanish were the first colonizing power to enslave Africans in the present-day United States, in 1526. However, that colony, in present day South Carolina or perhaps Georgia, struggled to maintain itself. The following year, the enslaved Africans revolted and the Spanish abandoned the colony (Brockell 2019).

In contrast, the English successfully established colonies along the Atlantic coast of North America, and therefore the establishment of slavery is normally dated to 1619, when between 20 and 30 kidnapped Africans were transported to Jamestown, Virginia. They were sold as indentured servants, that his, workers who had agreed to emigrate, but, in fact, they had been kidnapped. The growing agricultural economy demanded a large supply of cheap labor, but few Englishmen were interested in emigrating to spend their lives as farm hands. Between 1665 and 1705, many British colonies throughout the Americas adopted slavery codes. At first, the laws said that only a foreign-born non-Christian could be enslaved. Over time, the laws were amended so that enslaved people were considered permanent property, and the laws were also changed to allow Christians to enslave Christians of African descent. Chattel slavery in the Americas was a historically new approach to slavery. It was hereditary bondage, which was lifelong, inherited, and race-based. New World slavery was unlike anything the world had practiced before.

The next 150 years saw the rise of U.S. slavery, with Black Africans being kidnapped from their own lands and shipped to the Americas on the trans-Atlantic journey known as the Middle Passage. Once in the Americas, the Black population within the U.S. grew until U.S.-born Blacks outnumbered those brought from Africa. But colonial (and later, U.S.) slavery codes declared that the child of an enslaved person was also enslaved, so a permanent slave class was created and then continuously expanded by the doctrine that the children of enslaved women are also chattel.

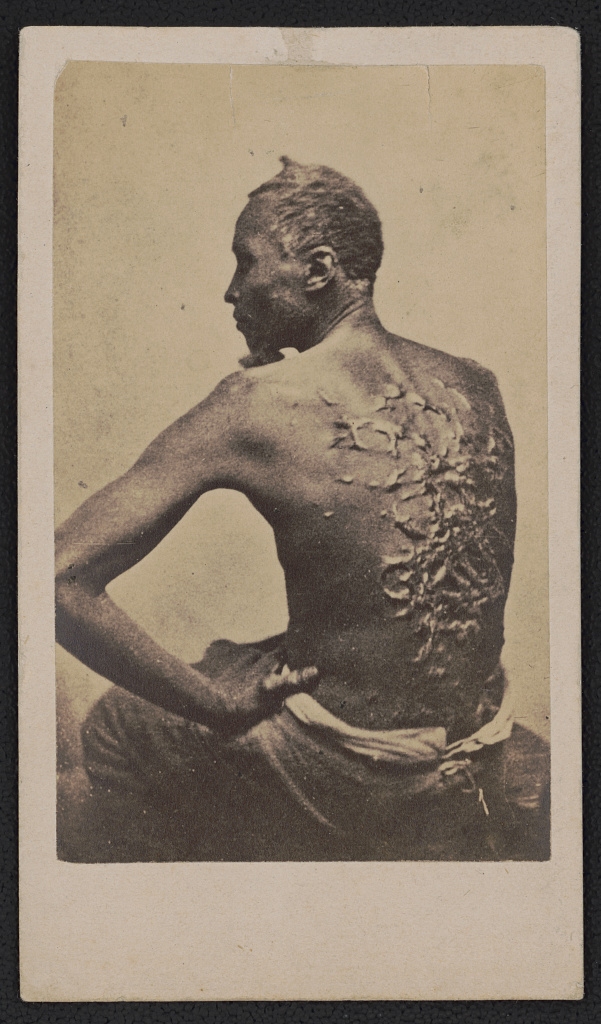

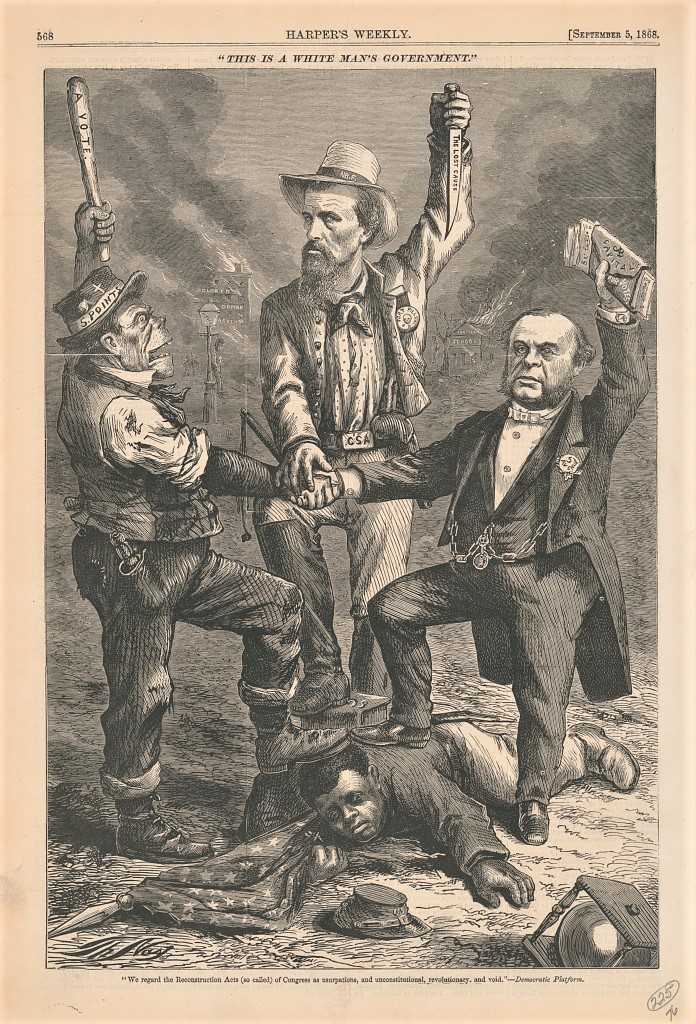

As a result of this system and its legal protections, there is no starker illustration of the dominant-subordinate group relationship than that of American slavery. In order to justify their severely discriminatory behavior, slaveholders and their supporters had to view Black people as innately inferior. Enslaved people were denied even the most basic rights of citizenship, a crucial factor for slaveholders and their supporters. Whippings, executions, rapes, denial of schooling and health care were all permissible and widely practiced. (See figure 2.6.)

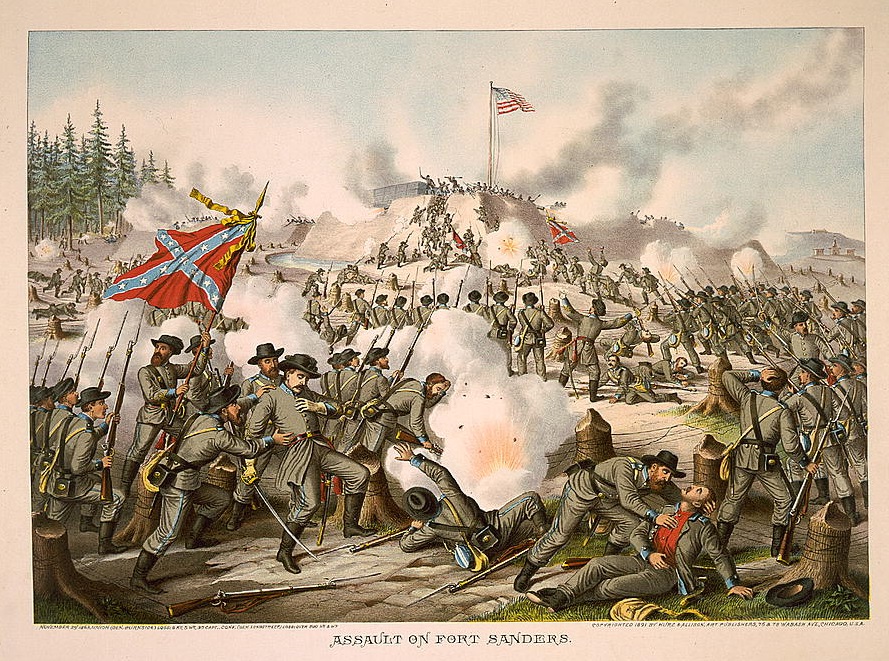

Slavery eventually became an issue over which the nation divided into geographically and ideologically distinct factions, leading to the Civil War. Slavery was abolished in 1865. The era of “reconstruction” of the country followed the war, and at first it seemed to promise greater equality for Black Americans. However, the former slave-holding states pushed back with a series of laws permitting and even requiring segregation of the races in public places, marriage, education, housing, and in most practices that involve social interaction. (See, again, figure 2.3.) Some northern states and cities followed. In practice, many Black people found themselves in a situation little better than slavery. In 1896 the Supreme Court gave full approval to racial segregation in the case of Plessy versus Ferguson. Homer A. Plessy had one Black great-grandparent and volunteered to challenge Louisianan’s segregation of public transportation by riding in a “Whites only” train car. Following the “one drop” rule that anyone with any Black ancestry was Black, Plessy was arrested, charged with a crime, and fined. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the separate but equal transportation facilities did not violate the U.S. Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment. Racial segregation was the law of the land for another fifty years. The major blow to America’s formally institutionalized racism was the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This Act, which is still followed today, banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Although government-imposed discrimination against Black Americans has been outlawed, the echoes of centuries of disempowerment are still evident. 2008 saw the election of this country’s first Black president, Barack Hussein Obama. However, he is actually of a mixed background that is equally White. Although all presidents have been publicly mocked at times (Gerald Ford was depicted as a klutz, Bill Clinton as someone who could not control his sex drive), a startling percentage of the critiques of Obama have been based on his race. The most blatant of these was the controversy over his birth certificate, where the “birther” movement questioned his citizenship and right to hold office.

2.6.c. Hispanic Americans

Use of the term “Hispanic” is almost unknown outside of the United States (Taylor, Lopez, Martínez, and Velasco 2012). Covering all groups for whom Spanish is their primary language, the term is most often used in reference to the Spanish-speaking areas of the Americas. Its use wrongly implies that there is a shared ethnic identity among all American peoples who came from Spain or who fell under Spanish rule. In reality, it embraces many distinct ethnic groups. Mexican Americans form the largest Hispanic subgroup the U.S., and also the oldest. Due to Spanish conquest, there was a Hispanic population in present-day California and the Southwest (especially present-day New Mexico) before the United States was formed. The United States did not begin to expand into these territories until the 1830s. (See figure 2.7.)

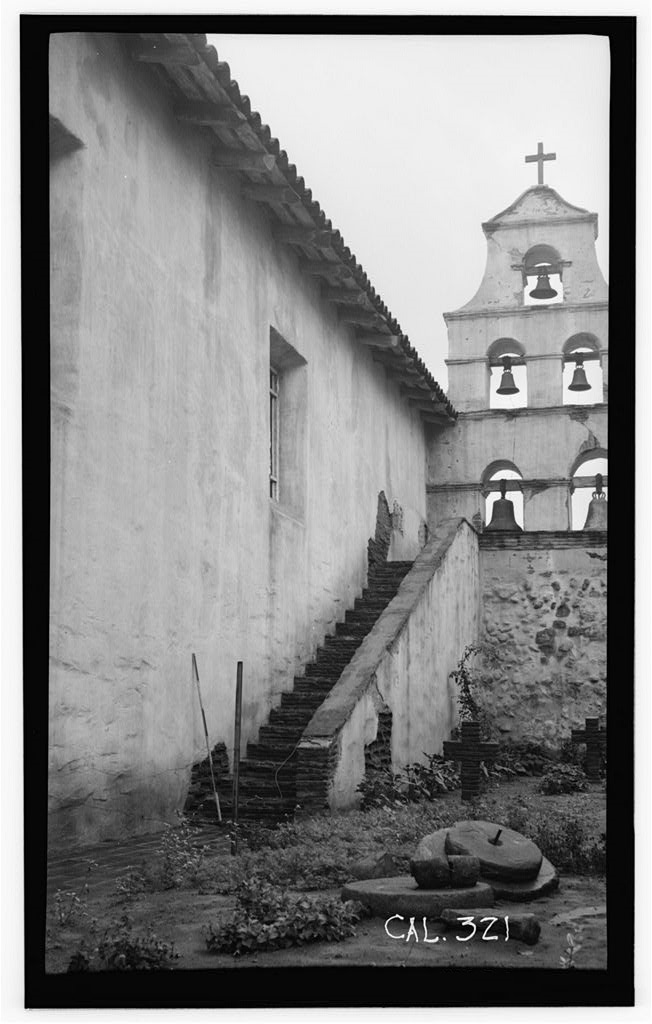

Spain took control of present-day Mexico with the conquest of the Aztecs in 1519. The colonizers gradually extended their control to the north. Permanent colonial outposts generally followed the establishment of Catholic missions that combined religious and government functions. Hispanic Americans extended Mexican governance — technically, New Spain — into present-day New Mexico and Texas toward the end of the 17th century. California followed in 1769 with the founding of Mission San Diego de Alcala. (See figure 2.8.) Expansion of the mission system continued northward until 1823, when the 21st California mission was founded at Sonoma, north of San Francisco. Sonoma would be the site of the Bear Flag Revolt of 1846, when U.S. citizens coordinated with U.S. military forces and took control of California by force. Although there was less violence, this land seizure followed the pattern of Texas, which had officially joined the United States in 1845. The current U.S.-Mexican border was established in 1848 after the U.S. victory in the Mexican-American War. By initiating a series of wars, the United States took control of areas where Hispanics were the dominant group and made them a non-dominant group.

Mexican migration to the United States increased in the early 1900s in response to a demand for cheap agricultural labor. Mexican migration was often circular; workers would stay for a few years and then go back to Mexico with more money than they could have made in their country of origin. The length of Mexico’s shared border with the United States has made immigration easier than for many other immigrant groups. Sociologist Douglas Massey (2006) suggests that although the average standard of living in Mexico may be lower in the United States, it is not so low as to make permanent migration the goal of most Mexicans who came to work in the U.S. However, the strengthening of the border that began with 1986’s Immigration Reform and Control Act has made one-way migration the rule for most Mexicans. Massey argues that the rise of illegal one-way immigration of Mexicans is a direct outcome of the law that was intended to reduce it. Mexican Americans, especially those who are here illegally, are at the center of an ongoing national debate about immigration. In his report, “Measuring Immigrant Assimilation in the United States,” Jacob Vigdor (2008) states that Mexican immigrants experience relatively low rates of economic and civil assimilation. He further suggests that “the slow rates of economic and civic assimilation set Mexicans apart from other immigrants, and may reflect the fact that the large numbers of Mexican immigrants residing in the United States illegally have few opportunities to advance themselves along these dimensions.”

Cuban Americans are the second-largest Hispanic subgroup, and their history is quite different from that of Mexican Americans. The main wave of Cuban immigration to the United States started after Fidel Castro came to power in 1959 and reached its crest with the Mariel boat lift in 1980. Castro’s Cuban Revolution ushered in an era of communism that continues to this day. To avoid having their assets seized by the government, many wealthy and educated Cubans migrated north, generally to the Miami area.

Cuban Americans, perhaps because of their relative wealth and education level at the time of immigration, have fared better than many immigrants. Further, because they were fleeing a Communist country, they were given refugee status and offered protection and social services. The Cuban Migration Agreement of 1995 has curtailed legal immigration from Cuba, leading many Cubans to try to immigrate illegally by boat. According to a 2009 report from the Congressional Research Service, the U.S. government applies a “wet foot/dry foot” policy toward Cuban immigrants; Cubans who are intercepted while still at sea will be returned to Cuba, while those who reach the shore will be permitted to stay in the United States. In contrast to Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans are often seen as a model ethnic group within the larger Hispanic group. Many Cubans had higher socioeconomic status when they arrived in this country, and their anti-Communist agenda has made them welcome refugees to this country. In south Florida, especially, Cuban Americans are active in local politics and professional life.

2.6.d. Asian Americans

Like many groups discussed in this chapter, Asian Americans represent a great diversity of cultures and backgrounds. The experience of a Japanese American whose family has been in the United States for three generations will be drastically different from a young adult who was adopted from Korea and brought alone to the United States twenty years ago. Asian immigrants have come to the United States in waves, at different times, and for different reasons. This section primarily discusses Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese immigrants and identifies some differences between their experiences. The most recent estimate from the U.S. Census Bureau (2020) suggests that about 6 percent of the population identify themselves as having Asian ancestry. At the same time, 86 percent of this group rejects the label “Asian American.” They generally identify instead with their specific ethnic group, such as Hmong, or Korean-American (Hernandez, 2023). Another complication is that the United States regards Native Hawaiians as Asian Americans. However, Hawaii was involuntarily taken over by the U.S. in 1898. So, not all ethnic groups that the United States identifies as Asian are due to immigration.

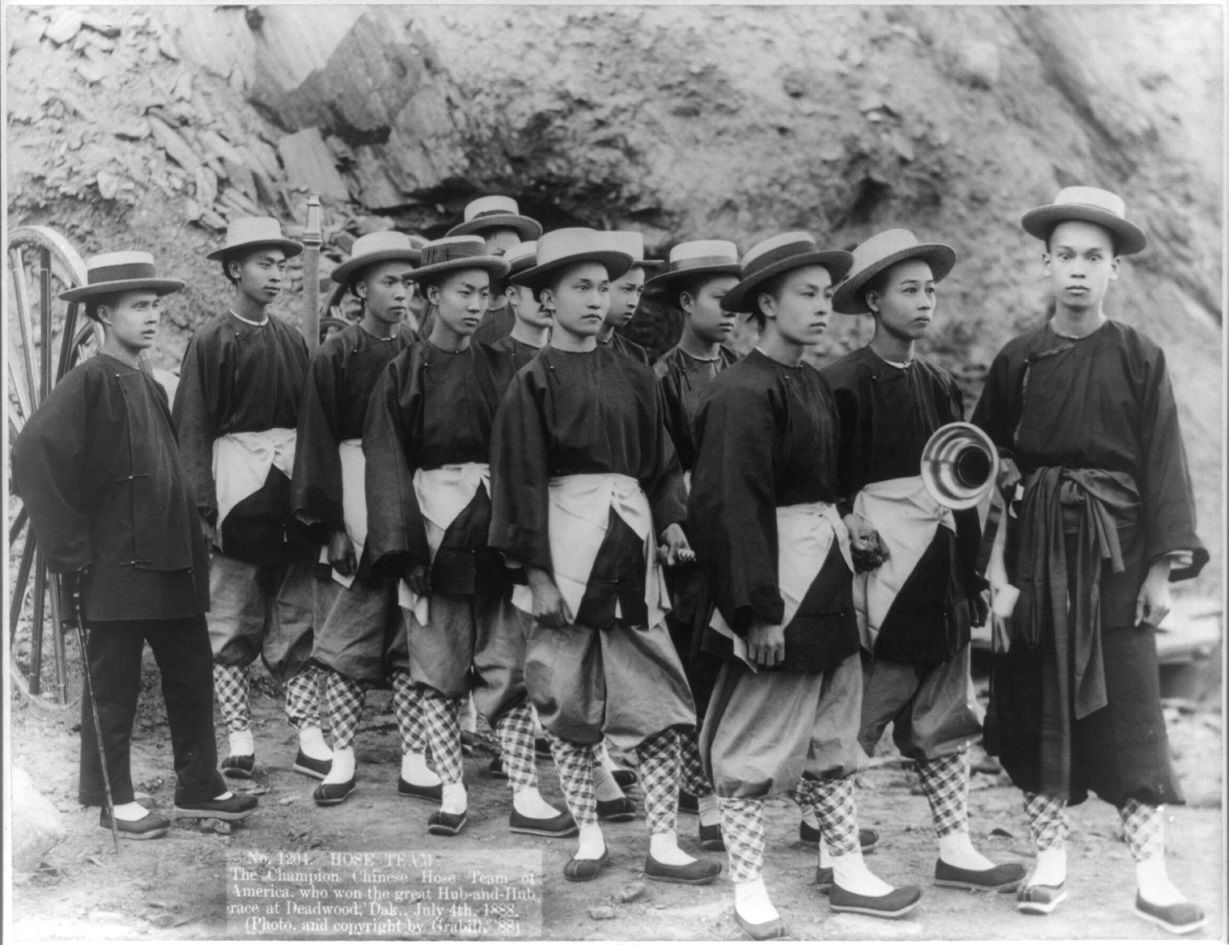

The first Asian immigrants to come to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century were Chinese. These immigrants were primarily men whose intention was to work for several years in order to earn incomes to support their families in China. Their main destination was the American West, where the Gold Rush was drawing people with its lure of abundant money. The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad was soon underway, and the Central Pacific section hired thousands of migrant Chinese men to complete the laying of rails across the rugged Sierra Nevada mountain range. Chinese men also engaged in other manual labor like mining and agricultural work. (See figure 2.9.) The work was grueling and underpaid, but like many immigrants, they persevered.

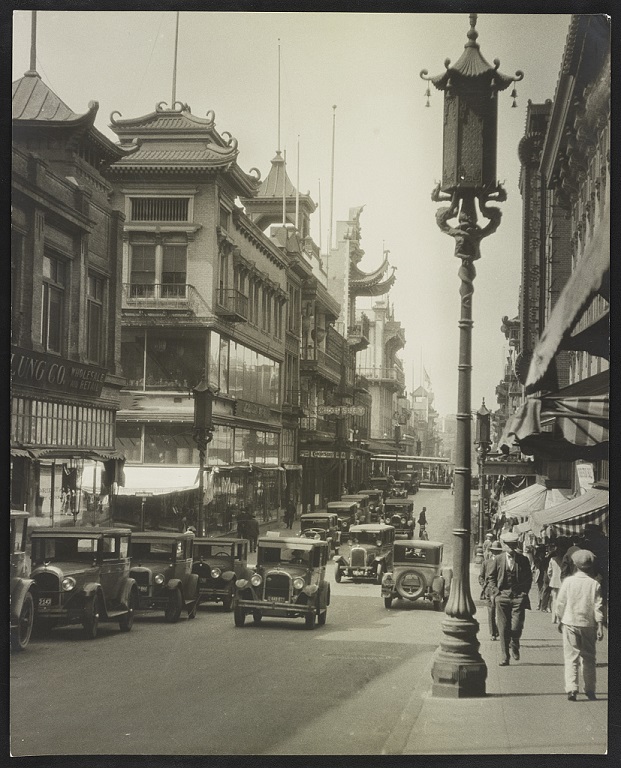

Chinese immigration came to an abrupt end with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This act was a result of anti-Chinese sentiment arising from a depressed economy and loss of jobs. White workers blamed Chinese migrants for taking jobs, and the passage of the Act meant the number of Chinese workers decreased. Chinese men did not have the funds to return to China or to bring their families to the United States, so many became physically and culturally segregated in the Chinatowns of large cities. (See figure 2.10.) Later legislation, the Immigration Act of 1924, further curtailed Chinese immigration. The Act included the race-based National Origins Act, which was aimed at keeping U.S. ethnic stock as undiluted as possible by reducing “undesirable” immigrants. It was not until after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that Chinese immigration again increased, and many Chinese families were reunited.

Japanese immigration began in the 1880s, on the heels of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Many Japanese immigrants came to Hawaii to participate in the sugar industry. Others came to the mainland, especially to California. Unlike the Chinese, however, the Japanese had a strong government that negotiated with the U.S. government to ensure the well-being of their immigrants. Japanese men were able to bring their wives and families to the United States, and were thus able to produce second- and third-generation Japanese Americans more quickly than their Chinese counterparts. Although Japanese Americans have deep, long-reaching roots in the United States, their history here has not always been smooth. The California Alien Land Law of 1913 was aimed at them and other Asian immigrants, and it prohibited aliens from owning land. An even uglier action was the Japanese internment camps of World War II.

So, despite the seemingly positive stereotype of Asian Americans as a model immigrant group, Asian Americans have been subject to their share of racial prejudice. The “model minority” stereotype is applied to a non-dominant ethnic group that achieves significant educational, professional, and socioeconomic levels without challenging the existing establishment. As applied to Asian groups in the United States, it can result in unrealistic expectations, by putting a stigma on members of this group that do not meet the expectations. Stereotyping all Asians as smart and capable can also lead to a lack of much-needed government assistance and to educational and professional discrimination.

2.6.e. Arab Americans

If ever a category was hard to define, the various groups lumped under the name “Arab American” is it. After all, Hispanic Americans or Asian Americans are so designated by reference to geography. But for Arab Americans, their supposed country of origin — Arabia — has not existed for centuries. Geographically, the so-called Arab region isn’t confined to the area that used to be called Arabia, which was the Arabian peninsula in southwest Asia, east of Africa. Instead of identifying “Arab” people with the Arabian peninsula, this classification of people comprises most of the people of the Middle East and parts of northern Africa. The major unifying feature of this vast region is that the dominant culture is historically Islamic. More specifically, the dominant culture reflects the Sunni branch of Islam. However, this is merely the dominant culture, coexisting with large Christian and Jewish populations. As John Myers (2007) observes, not all Arabs are Muslim, and not all Muslims are Arab, complicating the stereotype of what it means to be an Arab American. People whose ancestry lies in that area or who speak primarily Arabic may consider themselves Arabs. (See figure 2.11.) Despite the stereotype that all Arabic people practice Islam, Arab Americans represent many religious practices.

The U.S. Census has struggled with the issue of Arab identity. The Census does not offer an “Arab” box to check under the question of race. Individuals who want to be counted as Arabs had to check the box for “Some other race” and then write in their identity. However, when the Census data is tallied, they are counted as White. However, many such people do not self-identify as White (Want 2022), and many other Americans do not see them as White. According to the best estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau, the Arabic population in the United States is about 3.7 million people.

The first Arab immigrants came to this country in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were predominantly Syrian, Lebanese, and Jordanian Christians, and they came to escape persecution and to make a better life. These early immigrants and their descendants, who were more likely to think of themselves as Syrian or Lebanese than Arab, are the largest group within the Arab American population today (Myers 2007). Restrictive immigration policies from the 1920s until 1965 curtailed all immigration, but Arab immigration since 1965 has been steady. Immigrants from this time period have been more likely to be Muslim and more highly educated, escaping political unrest and looking for better opportunities.

Relations between Arab Americans and the dominant majority have been marked by mistrust, misinformation, and deeply entrenched beliefs. Helen Samhan of the Arab American Institute suggests that Arab-Israeli conflicts in the 1970s contributed significantly to cultural and political anti-Arab sentiment in the United States (Samhan 2001). The United States has historically supported the State of Israel, while some Middle Eastern countries deny the existence of the Israeli state. Disputes over these issues have involved Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine.

As is often the case with stereotyping and prejudice, the actions of extremists on September 11, 2001, have changed many people’s perceptions of the entire group, regardless of the fact that most U.S. citizens with ties to the Middle Eastern community condemn terrorist actions, as do most inhabitants of the Middle East. Would it be fair to judge all Catholics by reference to the sexual abuse scandals among its clergy? Of course, the United States was deeply affected by the events of 9/11. This event has left a deep scar on the American psyche, and it has fortified anti-Arab sentiment for a large percentage of Americans. In the first month after 9/11, hundreds of hate crimes were perpetrated against people who looked like they might be of Arab descent.

2.6.f. White Ethnic Americans

As we have seen, there is no non-dominant group that fits easily in a category or that can be described simply. The same is true for White ethnic Americans, who come from diverse backgrounds and have had a great variety of experiences. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2020), 57.8 percent of U.S. adults currently identify themselves as White alone (non-Hispanic). The early colonizers came primarily from western Europe, especially England and the Netherlands, but they were soon followed by Germans and large numbers of Scotch-Irish. (The Scotch-Irish are not Irish in ancestry or ethnicity. They are Scots who immigrated into the six counties of present-day Northern Ireland and who subsequently sent several generations of immigrants from there to the American colonies. Irish immigration came later.) In this section, we will focus on German, Irish, Italian, and Eastern European immigrants.

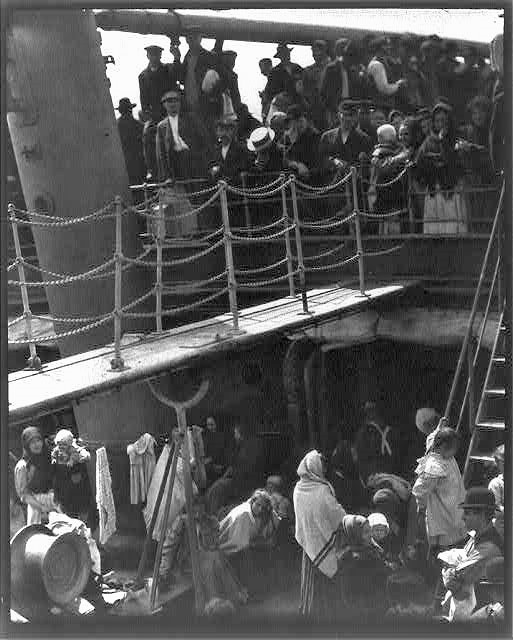

White ethnic Europeans formed the second and third great waves of immigration, from the early 19th century to the mid-20th century. (See figure 2.12.) They joined a newly minted United States that was primarily made up of White Protestants from England. While most immigrants came searching for a better life, their experiences were not all the same.

The first major influx of European immigrants came from Germany and Ireland, starting in the 1820s. Germans came both for economic opportunity and to escape political unrest and military conscription, especially after the failed European revolutions of 1848. Many German immigrants of this period were political refugees: liberals who wanted to escape from an oppressive government. They were well-off enough to make their way inland, and they formed heavily German enclaves in the Midwest that exist to this day. In a broad sense, German immigrants were not victimized to the same degree as many of the other groups this section discusses. While they may not have been welcomed with open arms, they were able to settle in enclaves and establish roots. A notable exception to this was during the lead up to World War I and through World War II, when Germany became an active enemy of the U.S. and anti-German sentiment ran strong. During World War I and after, many ethnic Germans avoided displaying any German affiliations and worked to ensure that their distinct ethnicity became invisible to most other Americans (Siegel and Silverman 2017). Immigration from Scandinavia was also strong during the same time period, with approximately 2 million immigrants, compared to 5 million Germans.

The Irish immigrants of this time period were not always as well off financially, especially after the Irish Potato Famine of 1845. Irish immigrants settled mainly in the cities of the East Coast, where they were employed as laborers and where they faced significant discrimination. In Ireland, the English had oppressed the Irish for centuries, eradicating their language and culture and discriminating against their religion (Catholicism). Although the Irish had a larger population than the English, they were an oppressed group. This dynamic reached into North America, where Anglo Americans continued to see Irish immigrants as a race apart: dirty, lacking ambition, and suitable for only the most menial jobs. For most of the 19th century, the dominant culture assigned them a social status barely above that of Black Americans. (See Figure 2.13.) By necessity, Irish immigrants formed tight communities segregated from their Anglo neighbors. There are now more Irish Americans in the United States than there are Irish in Ireland. One of the country’s largest cultural groups, Irish Americans have slowly achieved acceptance and assimilation into the dominant group.

German and Irish immigration continued into the late 19th century and earlier 20th century, at which point the numbers for Southern European and Eastern European immigrants started growing as well. Italians, mainly from the southern part of that country, began arriving in large numbers in the 1890s. Eastern European immigrants — people from Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, and Austria-Hungary — started arriving around the same time. Many of these Eastern Europeans were peasants forced into a hardscrabble existence in their native lands; political unrest, land shortages, and crop failures drove them to seek better opportunities in the United States. The Eastern European immigration wave also included Jewish people escaping pogroms (anti-Jewish uprisings) of Eastern Europe and forced segregation in what was then Poland and Russia.

The later wave of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe was also subject to intense discrimination and prejudice. In particular, the dominant group — which now included second- and third-generation Germans and Irish — saw Italian immigrants as the dregs of Europe and worried about the purity of the American race (Myers 2007). Italian immigrants lived in segregated slums in Northeastern cities, and in some cases were even victims of violence and lynchings similar to what Black Americans endured. They worked harder and were paid less than other workers, often doing the dangerous work that other laborers were reluctant to take on. Myers (2007) believes that Italian Americans’ cultural assimilation is “almost complete, but with remnants of ethnicity.” The presence of “Little Italy” neighborhoods—originally segregated slums where Italians congregated in the nineteenth century—still exist today. While tourists flock to the saints’ festivals in Little Italies, most Italian Americans have moved to the suburbs at the same rate as other White groups.

The obvious lesson is that “White” America forms the dominant group, but it is actually a coalition of multiple ethnic groups. The process by which they were accepted into the dominant group is socially complex, but it clearly illustrates that ideas about “race” and racial difference have been flexible. The distinction between White and non-White changed as different immigrant groups arrived in the United States. Racial identities that were initially assigned to unwanted groups (Irish, Italians) were later redefined as ethnic identities, permitting White ethnic groups to join Anglo Americans in the dominant culture.